Shot, Shocked, Saved

Flannery O’Connor’s story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” begins pleasantly, as a grandmother from Atlanta and her family embark on a road trip. These plans abruptly terminate when her son runs the car off the road and into the nest of a serial murderer. The Misfit (as he is known) banters with the grandmother while his accomplices pick off the rest of the family one by one. Finally, when she dares to reach out and touch The Misfit on the shoulder, he shoots her dead. Laying down his warm gun, shaking the blood from his hands, he then mutters: “She would of been a good woman…if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

I can’t speak for anybody else, but I’m unable to live according to these terms. Death isn’t so bothersome; every writer and artist (and citizen) has got to make peace with death, has to understand their relationship to it. What’s impossible to cope with is the shadow of the gun. The threat of violence, in my book, incapacitates completely. It induces mental chaos and blinding fear.

Recently, I encountered two new plays which triggered variations on this uneasiness, and got me thinking about the ethics and uses of violent or traumatic theater: Stephen Karam and PJ Paparelli’s columbinus, and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ Gloria. In her fiercely intelligent and important book The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, Maggie Nelson attends to the unanswerable question of whether artists should depict violence and cruelty in their work; whether—and if so, in what circumstances—it is defensible to add “more cruelties—both real and represented—to an already contemptible heap.” At issue here are both texts and images, across all forms and media: poetry, fiction, film, photography, and, of course, theater and performance art.

In live performance only, we experience the effect of violence on live bodies. What must we consider, then—as artists and audiences both—when deciding to employ or experience violence in the theater?

So I wonder: can replicating trauma and violence onstage in the image-glutted twenty-first century begin to purge and heal our audiences, to offer them some solace, knowledge, or even absolution? We must acknowledge that theater and performance bear an altogether different relationship to the representation of violence than do film and photography. The latter media have verisimilitude sewn up, for better or worse; and in live performance only, we experience the effect of violence on live bodies. What must we consider, then—as artists and audiences both—when deciding to employ or experience violence in the theater?

* * *

In the main, theater avoids the burden of film, which can descend to a mere pornography of violence, bloodless and gory both. But with the responsibility of our form’s more delicate relationship between art and reality, we as theater artists must instead be careful not to descend to the tactics of terrorism—most commonly, shock. I’ve been wrestling with whether I can start denouncing shocking or unpleasant theater wholesale. On the one hand, I don’t want to be shocked or assaulted. Nobody does.

I want an energizing theater, an uncensored theater. I want to encounter difficult art, whether contemporary or historical, that makes some difference, that may incorporate pain but at the same time might help us to live.

On the other, I want an energizing theater, an uncensored theater. I want to encounter difficult art, whether contemporary or historical, that makes some difference, that may incorporate pain but at the same time might help us to live. “If the book we are reading doesn’t shake us awake like a blow on the skull,” wrote Kafka, “why bother reading it in the first place?…A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.” The terms are violent, but the results—an awakening, a conscience brought from the subterranean to the enlightened—are most desirable. Still: if shock is merely an atomized instant of terror, and terror is anathema to art and life, is Kafka’s axe ultimately an instrument of creation, or destruction?

An attempt at an answer may be found by parsing the difference between shock and its more benevolent brother—surprise. The difference is simple, but profound, says Taylor Mac: “shock shuts you down; surprise opens you up.” Any moment in theatre which shocks is not especially useful. We’re blitzed, we’re numb, we seize up and fear obliteration. Taken to its extreme form, shock in theater could conceivably come in the form of a direct assault on our perceived safety as audience members. More typically, shock in theater is either the sudden imposition of something mildly to perniciously unpleasant onto the stage; or the accumulated dread of a play so mired in despair and ugliness that we leave the theater feeling as if our capacity for existence has been extinguished.

The French lunatic Antonin Artaud articulated a series of aesthetic theories in the 1930s, all bound by the idea of a “theatre of cruelty.” The aim of this theatre was to “cleanse audiences spiritually by rattling them viscerally,” as Michael Feingold put it in a 1993 review of Reza Abdoh’s Tight Right White. Artaud wanted “extreme action, pushed beyond all limits”; not blood and guts, but “a pure cruelty, without bodily laceration.” After “having been transfigured by the vicarious experience of violence,” Feingold writes, an audience would be “incapable of participating in or even imagining violence.”

Artaud never managed to create a theatrical spectacle that supported his theories in his lifetime, though some who have come after him have tried, in all media. By “pure cruelty,” Artaud was speaking more of a rigor, a clarifying specificity. (It is this interpretation of cruelty that Anne Bogart advocates in her writings on violence in the rehearsal room: the violence of a decision to obliterate all other options.) Applied too literally, Artaud is doomed to failure, says Nelson: “Any time an audience remains intact enough to shuffle out murmuring how powerful before deciding where to have its pie and Schnapps, Artaud’s dream of ‘crushing and hypnotizing the spectator,’ perhaps to the point of no return, has died.” This is because there’s no way to make room for shock except to ignore it, to move on from it. It’s a violation. It’s an impediment to functioning. Put another way, you can’t break somebody down if you’re not prepared to at least begin to build them back up, to point to the rope that leads out of the oubliette. Anything else is sadism of the worst kind. It’s the difference between ingesting poison against one’s will and shooting a finger of pure, clean, high-proof gin: bracing, acrid, but, after a moment, revitalizing—even healing.

Along these lines, I believe we as creators should always aim instead for surprise, which implies some measure of consent between the audience and the artists. Nelson writes that

[c]onsent and warning are not acquiescences to arbitrary, repressive notions of decorum or authority. Rather, they are space-makers, and they allow for the very possibility of voluntary submission or emancipation. The desire to catch an audience unawares and ambush it is a fundamentally terrorizing, Messianic approach to art-making.

That’s not to say that there should be no room for surprise, because there should be. “Something surprising should happen every ten seconds,” says Mac. But it’s important to have some sense of the evening in store, and to be able to consent knowingly to the next two hours. It is a cruel thing to permit anybody to buy a ticket to a play like Sarah Kane’s Blasted, which depicts extreme sexual violence and bodily mutilation, without letting them know that the experience in store will test them, to say the least.

* * *

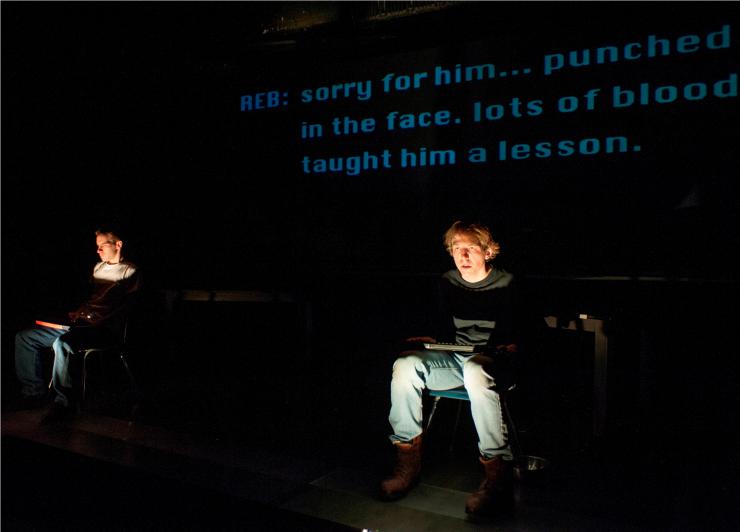

Two recent plays trouble this idea of informed consent, as well as the simple categories of surprise and shock: columbinus, written by Stephen Karam and the late PJ Paparelli and presented first at Chicago’s American Theatre Company and later at ArtsEmerson, where I saw it in the fall of 2013; and Gloria, by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, which was premiered by New York City’s Vineyard Theatre this past summer.

columbinus makes no attempt to obscure its topic: the shooting at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999. I saw the play as part of a class assignment, but I had decided some months earlier, when posters went up on campus at the tag end of the previous semester, that I would see the play, despite my trepidation at witnessing a piece about the events in question. The poster showed two actors, presumably playing Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, one leering into a camcorder, the other behind him, out of focus but intent on something unnameable and malevolent. They were people with a story. I decided to trust Karam and Paparelli to lead me down a dark path: I consented to experience whatever columbinus might be.

Act Two: the 911 call starts playing and I freeze in my seat and curl up, terrified that in a second I'll start hearing actual gunshots and actual screams on tape. The action onstage: carried out without blood, but steeped in terror. The actors had guns; everybody else was crying and cowering…I was as close as I'd ever come to a lived experience of trauma, of the shadow of the gun.

I left the theater that night angry for being exposed to that simulacrum of terror, and pitying the actors who had to carry it out. It's one of the most complex reactions I’ve ever had to a piece of theater. I was rattled by the proximity to terror, albeit simulated; I was disturbed at how human Karam and Paparelli had made the shooters and their victims seem. In the previous year, I had lived through news of the Sandy Hook shooting (next door to my own hometown in Connecticut) and the Boston Marathon bombings, which had occurred six blocks from Emerson. I reacted to both, oddly enough, with shock: with a great blank where feeling should be. When things like that happen, events that are like nothing that's happened to you before; and you're a part of them, close to the tragedy but not close enough to have witnessed them directly; and all you have for a guide is a Facebook feed and some hot prickly fear and a useless wish that the guns were gone and malice wiped from the earth: you have nothing.

columbinus was a reproduction of trauma, but carried out in a safe space. Paparelli and Karam’s goal was not to terrorize, as Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold had, but to, after all, edify, to make an attempt at understanding what happened in Littleton, Colorado. Nelson, via Freud, posits that our enjoyment of, or in this case, perhaps, our surprise at a work of art “stems from art’s ability to offer—perhaps to viewer and creator alike—retroactive mastery of traumatic experiences that one’s defenses failed to deflect adequately from the organism at the time of the original impact or injury.” Sometimes, the particulars of a tragedy can reach our ears, but, frustratingly, they don’t mean anything. The world is too noisy, the trauma too titanic to pierce our armor. When things get personal: that’s when reality can start to feel like reality. The play offered me was a version of the experience of Sandy Hook and the Marathon bombings that I could feel, and threatened my serenity, shook me up, made me uncomfortable, but productively. I am sure I am not the only one in the audience who felt this.

“Terrorists are the new novelists,” writes “writer of wayward nonfiction” David Shields, in his “quarrel” with Caleb Powell, I Think You’re Totally Wrong. “What novel could touch Columbine?” Answer: a reenactment, a pageant, with context, speculation, two hundred breathing bodies working in concert to understand this event, the origin point of this whole mess, this history of violence. I also do think Shields is totally wrong, here (though usually he’s completely spot-on, for me; no writer has taught me more about mortality, literature, or the art/life problem): I won’t grant any artistic or narrative clemency to bullies with guns. It is so easy to spread terror, to suppress, to shut down, to use force and force only. It is not easy to dance with grace, to limn the sometimes nasty surfaces.

* * *

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s Gloria, a play which I elected not to see in its original run, contains a shocking twist at the end of the first act that completely alters the kind of play we have been watching for the past fifty minutes. The title character, resident oddball at the offices of a New Yorker-esque magazine, whips out a gun and starts shooting, killing half the cast, including herself. Prior to this point, the play purports to be a pleasantly acrid workplace comedy, with some archetypal inhabitants (a semi-dipsomaniacal gay writer; an earnest intern whom the editors ply with busywork). The marketing materials for the play did not make any mention of the shooting. The principal image was an overhead shot of a man and a woman seated at a desk, with red X’s painted over their heads (and a mug of coffee). “An ordinary humdrum workday turns anything but,” promised the copy. It warned: “Gloria contains disturbing content, which may not be suitable for patrons under 17.”

I can’t entirely take umbrage with a play in 2015 toodling along, only to be interrupted by a lone wolf with a handgun. It's a sadly familiar scenario, one for which we never have any warning, either, whether as victims, witnesses, or citizens reading the headline. I self-selected as someone who was sensitive to this, who didn't want to be terrorized or to witness actors get shot just a few feet from my seat. (I wasn’t expecting Tarantino, but I knew special effects had advanced somewhat since Hedda Gabler. I don’t even see movies with gun violence.) I eventually saw Gloria on my own terms: I went back and watched the official recorded copy of the play at the New York Public Library’s Theater on Film and Tape division. The shooting was upsetting, for sure—I watched it with my notebook in front of my face, even though (because?) I knew it was coming.

I was pleasantly surprised, however, by the events of the second act. In a way, I felt as if I had survived a shooting myself, as Jacobs-Jenkins turned his attention to how the actual survivors of the tragedy coped with the trauma. Dean, the wannabe-memoirist, witnessed most of the carnage—Gloria spared him because he was the only one who attended a party she’d thrown the night before. He’s sobered up in more ways than one, and admits what we’re all thinking—or at least I am—about the aftermath of trauma: “Life rolls on, but I’m not ready. I can’t be the only one who’s not ready.”

Gloria is effective because, while its violence is a shock, just like all shootings are in “reality,” it follows through and depicts several different identifiable reactions to trauma. I do look askance at the playwright’s framing of the violence as an unexpected twist, and I wouldn’t bury that particular lede in a play I wrote myself. Ultimately, though, I exited the viewing of the play feeling brightened, and more capable in my fortitude to survive the horrible events of the real world outside the library, which is more consolation than I get from the news.

(I realized later where this feeling may have come from. The play is performed by an ensemble of six, and every actor whose character died in Act One returns to play a different major character in Act Two; this is a feature of Jacobs-Jenkins’s script, and not a purely economic move. Even Jeanine Serrales, Gloria herself, returns as Nan, a survivor who exploits her harrowing story to ethically dubious ends. The doubling has the odd effect of making the shooting seem like it never happened, since everyone I had seen die was clearly still alive. I'm still not certain whether this is a therapeutic asset or an obfuscation; either way, it doesn't diminish the intelligence and excellence of the play itself, which is another jewel in Jacobs-Jenkins’ crown.)

* * *

And I’ll return to Kafka's axe. I believe he intends that the piercing of the frozen sea be a positive occurrence, a lifting of the veil. All such rendings require violence, though; all growth requires pain. In this belief he is allied with Artaud, when Artaud veers into coherence. Kafka goes on, however, into his own realm of desolation: “What we need are books that hit us like a most painful misfortune, like the death of someone we loved more than we love ourselves, that make us feel as though we had been banished to the woods, far from any human presence, like a suicide.”

The art I wish to see and create provides some context or advice for survival, even if it is eclipsed in magnitude by the horrors that precede it.

This is too far. This is shock, terror, and defeat. The art I wish to see and create provides some context or advice for survival, even if it is eclipsed in magnitude by the horrors that precede it. This isn’t didacticism. It’s a refusal to add to the sum total of cruelty that exists on the planet, at least without balancing the scales a bit. We can return to the scene of the crime onstage, and we can invent new, fictional crimes that mirror our weary reality—and we should. Theater is now at a wonderful advantage, in its elemental distance from text and video, which dominate the means of our everyday exposure to both cruelties and banalities.

Shock doesn't work. We’re not terrorists. Surprise me.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

When it comes to finding the balance between shock and discomfort theatre treads a really thin line. Because of a live audience in theatre we have a much deeper connection between the audience and the performance. In films it's very easy to dissasociate oneself from the violence occurring on screen because its 'on a screen'. While in theatre watching something gruesome or cruel live means there's no escaping the act. We can't distance ourselves in the same way because it's not a pre-recorded sequence. This personal connection is exactly what makes theatre so powerful. But it also raises the question of when should one stop. What are the limits to what you show on stage? I think 'theatre of cruelty' is relatively unsuccessful because it is too over the top and leaves the audience too uncomfortable. Testing their comfort is alright but leaving them shell shocked and sickened takes away from the story because the audience is drawn out of the story world. Because in theatre we tell stories that are often linked to personal experiences or the times we live in its understandable why some plays use that violent shock factor. But I think if you want the audience to really believe and become immersed in the story one has to keep the audience comfortable enough that they don't jump out of the story and start thinking of their own discomfort or disbelief.

An interesting take on violence in the theater -- similar to (but deeper than) my take earlier this year, also on Howlround. I talk about Gloria as well, plus Guards at the Taj, and talk to Bryan Doerries about the potential healing nature of tragedies that deal one way or another with violence.

http://howlround.com/violen...

Really insightful read. I'm at a loss for words to attempt to describe how I, as an actor and supporter of the performing arts, feel about violence on stage. I performed in The Pillowman and wasn't versed enough at the time to truly give it the respect it deserved.

Thanks for reading, Shaun! The Pillowman is actually the one play Maggie Nelson talks about at length in her book. "Part of The Pillowman's cruelty is that we, like Michal, have now internalized these sickening tales (not to mention another—that of The Pillowman itself). The question of what effect they might have on us—on our psyches, our souls, our social landscape, and our deeds—has become our burden to bear."

In an attempt to further understand your point and make sense of our duty as artists to bring stories of violence to the stage I reread the article. One piece that is sticking out to me, your quote about columbinus "Paparelli and Karam's goal was not to terrorize, as Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold had, but to, after all, edify, to make an attempt at understanding what happened in Littleton, Colorado." I don't know if I agree with your assessment of what the playwrights were attempting to convey here. Though it makes the most sense as to 'why' anyone would want to immortalize a sickening real event like Columbine on stage I wouldn't jump to the conclusion that they were not attempting to terrorize the audience in some way. How could the audience feel anything but terrorized? You said yourself that you left feeling angry, numb, and not quite sure what you had learned from the experience. I would go a step further and say that it is a play that probably shouldn't have been produced simply b/c it basically made no attempt to edify the events. If it were wrapped into some bigger narrative about high school bullying or gun violence then ok. But here we have a play that puts Eric and Dylan in the limelight and forces us as an audience to sit through the actually sounds of terror that took place. My question is: How is it justifiable to bring this reality to the stage? And if we must, What is the ultimate end? To me columbinus is shock for shock sake. Whereas Gloria is at least attempting to give us hope after a traumatic event.

I agree in the end...give me surprise.

I've heard from friends who agree with you, that columbinus is shock for shock's sake. Have you seen or read the show? The events of 4.20.99 are confined to the second act, what I remember as the shortest of the show. The first act is a "day in the life" story about teenagers at a generic high school, which only turns into Columbine HS over the first intermission. The third act (written for the second incarnation of the play) is essentially the Columbine version of "Laramie: Ten Years Later." I'll be honest: I don't remember much about the third act because the second blitzed me so much.

Paparelli visited my class the day after we all saw the play, and I can vouch here that he and Karam did not intend _merely_ to terrorize. By that I mean: even if I was terrorized in act two, it felt productive. I had spent an act and a half getting inside Dylan and Eric's skin and learning their story. That is immensely valuable, because stories are powerful, and always, always introduce nuance and some measure of unexplainable empathy. (Because humans are humans.) It is surely not a problematic play in the sense that it valorized Dylan and Eric—that's a false reading; they didn't put those kids in the limelight to increase their airtime and condone their actions.

Sometimes, the pain inflicted by art is a good thing (and my ability to freely consent to columbinus given its subject matter, and to trust Karam and Paparelli as benevolent artists, is important). Would I see columbinus again? Probably not. Would I work on a production? No. Would I write a show about a mass shooting, real or imagined? I don't think so, but making art about what makes you anxious is very useful—as long as you do not intentionally or accidentally merely transfer your anxiety to an audience, to purge it that way. There's a philosophy (well, really a pretty proven science) about trauma and fear that you do yourself a disservice and delay your healing by avoiding what upsets you—hence why trigger warnings are by and large more harmful than helpful.

But you are right. It's thorny and nuanced, and my results aren't typical. I felt the same way that you did about Gloria when I had only heard about the givens of the show, but going out and watching it eventually, I found surprise. I think sometimes we have to take a gamble with art.

Well put! Thanks for the reply.

Rob,

Thank you for writing such a thoughtful and important article. I will be giving it some thought and sending a link to some theatre friends for them to read. I basically agree with your perspective, and do sometimes wonder what seemingly escalating disturbance in the collective consciousness is needing and creating the shock and violent phenomenon. Interesting that you mentioned 'Blasted' as I saw it on tape at the Library for the Performing Arts. It was probably the most disturbing play I've ever seen, and yet at the same time I could not help but marvel at the skill in writing of someone so young. But did its unrelenting despair and violence ultimately enrich my life in some meaningful way? No. Was the authoress a gifted writer? Yes. As I age I find myself increasingly seeking and cherishing those theatre experiences that ultimately, even if traversing through pain, reveal, open, suggest, instruct, imagine or surprise me with possibility.

Thank you for reading, Michael, and for sharing your thoughts. Yes, I haven't seen or read Blasted, and I may never. I've read _about_ it—Michael Billington has some great things to say about it in "State of the Nation," a great history of postwar British theater. Blasted at least does have a worthwhile political element to it, which is more than can be said about nasty plays like Philip Ridley's Mercury Fur and other In-Yer-Face plays. It's all nuance, but definitely, I think, something audiences and creators should struggle with and make deliberate choices about.