Invitation to Interpret

An Audience Makes Meaning Together

A young man strains to lift a cooler full of ice above his head, struggling to keep it aloft as a friend looks on. A woman, sitting across from a realtor, confides her worries about being able to afford a home. Another stands, bemused as a friend offers the audience an unflinching description of his physique. They are actors, but they are playing themselves in an audacious experiment called The Sincerity Project, a twenty-four-year production slated to run alternate years until 2038. The work limns the passing of time, the aging of audience and actors, the way bodies change, and the shifting ground of human relationships.

The deeply personal subject matter and the experimental form of Team Sunshine Performance Corporation’s The Sincerity Project provided an opportunity to ask questions about how and why audiences make meaning out of experimental theatre. FringeArts, a premier presenter of experimental and contemporary performance in Philadelphia, partnered with Team Sunshine, devised theatremakers, and creators of The Sincerity Project to study audience engagement and look for authentic moments of connection. With support from Doris Duke Charitable Foundation’s Building Demand for the Arts project, we were asked to conduct a series of focus groups with participants ranging from Team Sunshine’s most ardent fans to people who don’t attend theatre at all. For the latter group, we interviewed thirteen of them about their cultural habits and beliefs before they saw The Sincerity Project, then gave them a free ticket to the show, and brought them back a few weeks later to tell us what they thought of the experience.

We expected to learn about ticket pricing, front of house procedures, expectations set by marketing materials, and the audience’s threshold for experimental content. Yet what we ended up talking about … was far more personal, illuminating, and complicated.

The third and fourth focus groups brought together four men and five women from across the Greater Philadelphia area, recommended by participants in the first two groups. They had not seen a Team Sunshine performance before. We expected to learn about ticket pricing, front of house procedures (called the “on-ramp” by one participant), expectations set by marketing materials, and the audience’s threshold for experimental content. Yet what we ended up talking about with our brand-new audience members was far more personal, illuminating, and complicated.

The work itself influenced the conversations in two ways. First, The Sincerity Project explores universally personal topics. It is a devised piece in which an ensemble reflects on their lives, hopes for the future, and relationship to one another and the world around them. Every two years for twenty-four years, the ensemble will reconvene to devise a “Sincerity Project”—2016 was the second installment. There are, as you would expect, stories about broken expectations, changing dreams, disappointments, and surprises. The audience can forecast the future on the performers’ bodies, wondering “what will it look like to see them doing that dance when they are forty? When they’re sixty?”

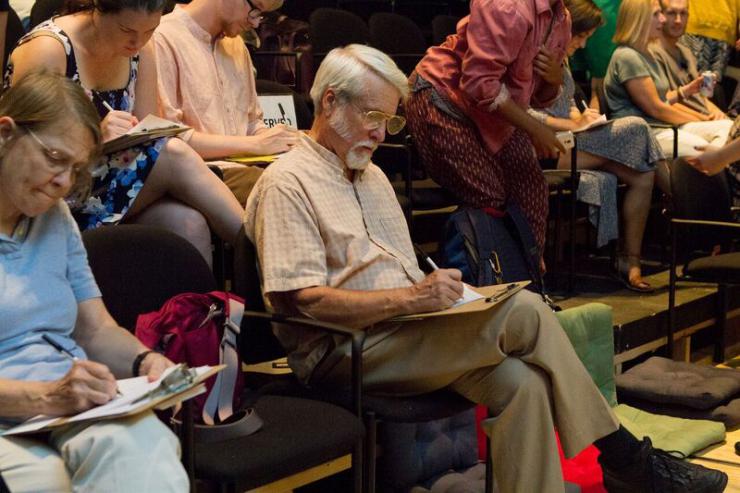

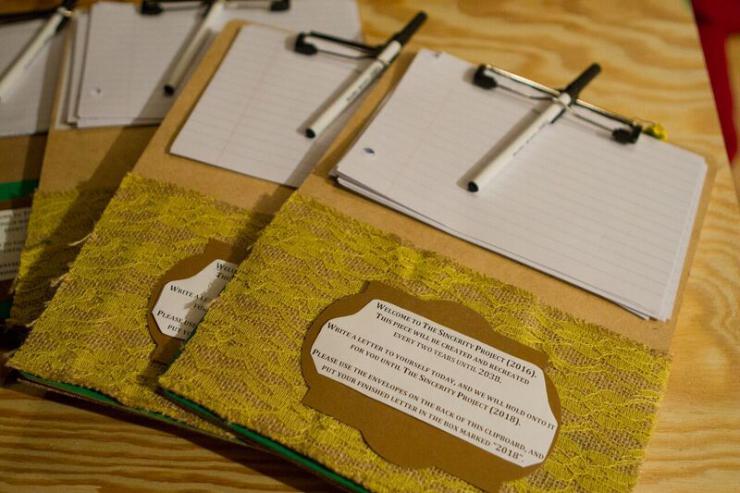

Second, Team Sunshine creates a carefully designed audience experience environment before and after each Team Sunshine show. In the case of Sincerity Project, there were interactive activities, a bar with alcohol, music, and conversation prompts placed around seating areas. Furthermore, the front of house staff exhibited a tone specific to the production, “calm and warm” for the pensive Sincerity Project, as opposed to a more “psyched and ready” tone for a high energy physical piece like Team Sunshine’s earlier piece Punchkapow. After passing through the fully designed lobby experience during The Sincerity Project, audience members walked onto, and across the stage in order to get to their seats. On stage right were boxes of sealed envelopes. Two years ago, Sincerity Project’s 2014 audiences wrote a letter to their future selves and Team Sunshine kept them. Those who attended the first installment pick up the letters they wrote in 2014. Others use clipboards to write themselves a letter they’ll receive when they come to the 2018 iteration of the show. Seated on set pieces and sprawled on the stage floor, audience members read, write, whisper to one another, and gaze off into space contemplating what to write to their future self. We hope this put them in a reflective space, in which they can better see themselves in the performers’ stories.

We took advantage of our new audience members’ capacity for reflection to learn what works for them and what falls short when it comes to participating in the arts. In the focus groups, participants shared with us what turns them off when they go to the theatre: poor performances from actors, low production values, stressful box office experiences, uncomfortable seats, the inability to leave to use the restroom, and exceptionally high ticket prices. But as artists and producers, we are mistaken to believe that providing the opposite is enough to turn them on. These audience members wanted to grow, see, reflect, and better understand themselves and others. They asked time and again for a “takeaway,” which to be honest, not all audience members felt they got. One participant, Patrick*, a white man in his sixties, who retired after thirty-two years with a major American airline, was eager to participate in the focus group process, but worried that he didn’t have the analytical tools to interpret what he just saw.

I thought I was sick and I wasn’t getting it. But afterwards my two friends and I, we went to a place to have a few beers and I said “I didn’t get the theme of the story.” I liked sitting on the stage, I thought that was a cool aspect of it. And it was so close and intimate, but…whatever, my head, I didn’t get it.

But as the conversation went on, Patrick found his footing and realized that he had his own valid interpretations of The Sincerity Project, and didn’t need to rely on his friends’ interpretations. Attendees’ ability to get a strong takeaway depended on two things: the permission to interpret what they saw, and the opportunity to make meaning collaboratively.

Permission to Interpret

Some new audience members, like Patrick, expressed anxiety over “getting it.” Some believed that if they didn’t like something, it was because they “missed the point,” or that they required an analytical toolkit to discuss the work. Audience members required time and space, as well as respectful encouragement, to feel ownership of their experience of the work, which is especially challenging in experimental performance and work without a conventional narrative structure. The ability to participate in the focus group itself supported their process of meaning making through probing questions and affirmation from their facilitator of the validity of their perspectives, even ones that questioned the work or disparaged it.

Furthermore, several participants noted that they engaged more deeply because, a) they knew they would be asked to reflect on it at some point, b) they had a few weeks to collect their thoughts, discuss with people in their lives, and let it sit in their minds.

Meaning-making Through Communication with Others

At the beginning of the focus group a few weeks after the show, participants were hungry to ask, “What did you think that meant?” to one another. James*, an Asian architect in his thirties, half-jokingly told the group: “I was really looking forward to coming here because I really wanted people to explain to me what I have seen!”

Given encouragement and validation that all interpretations are welcome in the space, participants collected interpretations, marveled when they saw things differently, debated and laughed, and many came to their own conclusions by the end of the conversation. Many realized that they saw themselves in the work, even if they didn’t like the show at first. Wendy*, a nonprofit professional in her twenties, explained:

I really did relate to the one girl who was having trouble dating; I can relate to that. Whereas someone else may relate to the broken relationship. So I think you go in and you kind of put your own stuff on it, and that could either give you a very positive or very negative interpretation.

Not all agreed that the performance had value for them; one person even said to another participant; “When you said it clicked with me—nothing clicked with me in that show.” These conclusions were valuable because they were personal, crafted to directly apply to each person’s understanding of their lives and the lives of those around them.

These audiences wanted to know that by listening to other people’s stories, they’d be better able to author their own, if only in their own minds.

What Have We Learned?

As artists and advocates devoted to turning these findings into action, the focus group experiment taught us a few things that would serve audiences like these more completely. First, we are hoping to flip our focus from selling audiences what has been created, to the burning questions of why and how that fueled its creation. Our new audiences weren’t looking for a promise of “great art,” as much as the promise of “a takeaway.” The truth is clear to us: the art has to be have depth and resonance for the takeaway to exist. But that might not be what we lead with. These audiences were not deeply drawn (as we are) to a new piece that innovates upon a form (performing the same thing every two years for twenty-four years), but that its makers are a complex mash-up of people searching for meaning in life. In their 20s and 30s, the ensemble is working to reconcile the compromises that are made by living in relationship to other people over long periods of time. They are realizing that being alone doesn’t mean being lonely, and thinking about what tattoo they should get next. They are wondering where they’ll be in two years, and feel weird that they aren’t where they thought they’d be two years back. Except for some of them, who just don’t get stressed about that kind of stuff. These audiences wanted to know that by listening to other people’s stories, they’d be better able to author their own, if only in their own minds.

Our practice will change based on this research, and believe it is transferable to other organizations. First, we feel affirmed to continue our work in audience experience design. Kimmy*, a regular theatre-goer and member of the first focus group, described the pre-show experience as follows:

It was kind of like the perfect mood, I thought. It took away from the awkwardness of standing around waiting for something to happen. like it creates a connection between the audience members, we can joke about something. We can laugh or maybe talk about something, feel like you’re part of something together.

We realized that artists have to direct the front of house as carefully as they direct their actors (which is why we value ongoing partnerships with progressive presenters like FringeArts. We noticed several moments when focus group members were nudged into an emotional and mental place because of that design. Our continued work in this arena will include:

- Thoughtfully designed lobby spaces that express the creators’ goals for the audience

- Front of house staff directed as tour guides, responsible for the tone and culture of an experience

Second, in marketing to audiences new to experimental work, we will prioritize the burning questions that fuel the artists over the works’ form and artistic innovation. To speak more clearly to potential “takeaways,” we hope to say “Are you thinking about this? So are we.” Our work in this arena includes:

- Articulation of broad questions and interests, over specific narrative or thematic points

- Earlier and more generative conversations between artists and marketing and communications teams

- Ongoing artistic conversations about questions being asked widely in our city, country, and world

Lastly, we will promote agency in interpretation by finding ways to validate multiple interpretations, break through cultural norms that require an audience to “get it,” and promote debate and conversation amongst audiences. Our work in this arena includes programs that:

- Bring audience members together in conversation without the artists present

- Host programs facilitated by outside observers and fellow audience members

- Allow for more time between consuming the work and talking about it

For initiatives that, a) seek to deeply learn about our audiences, b) require audiences to move significantly outside their comfort zone, we will explore compensating them to participate and providing free tickets to selected shows.

We will close with a final reflection from audience member Jaime*, a systems administrator in his early thirties, who seemed to really embody our hope that audience members new to the arts would feel permission to make The Sincerity Project their own, without needing a degree in critical theory, or prior acting experience. Jaime opened up about his post-show experience, and how he was excited to bring his own journey back to the focus group table to share with others who took this risk with him:

I jumped in a cab and I went home and laid in bed and stared at the ceiling … It made me think a lot about myself—where I am? Less about what actually happened in the show. But more—what I would do if I was in the show? And what I might say about those things? It just allowed me an excuse to do an inventory of my life and think about where I am.

*Names have been changed.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

interesting stuff, but why are only some of the participants' race and gender described and not others? it's inconsistent and a little distracting, and doesn't really seem to add anything to the article. did no one proofread this?

Thanks for the question, xanthus, it's a good one and I'm glad to have the chance to explain the process of selecting descriptions. When writing this piece, we corresponded with the quoted participants to be sure we took their words in the intended context, and to be sure the overall themes were in line with their experience of being part of the focus group. Part of that exchange with them included each quoted participant deciding how they would like to be described. They chose different qualifying information (race, gender, age, occupation). That's why it is inconsistent, but hopefully presents the truest sense of how each of them identifies, since they chose the descriptions themselves.