(Women’s) History Matters

How Many Plays Can You Name?

For many years as an adjunct professor of playwriting, I never felt a responsibility to introduce my students to “the canon” of dramatic literature. I was a teaching artist, not an academic, and while I would talk about plays being produced locally and nationally, often bring in a scene to illustrate craft, and recommend plays and playwrights I thought my students should read, I resisted including plays on my syllabus. The focus was on play writing, not play reading. This seemed to work for most of my career, since I taught in a conservatory where I could assume the students already knew what plays were. When I started teaching in a university’s English department about five or six years ago, though, I encountered students who’d never experienced a play before. Clearly my old methods were not going to work.

Around the same time, an email from History Matters/Back to the Future dropped into my inbox with an invitation to participate in their One Play at a Time initiative. Registering meant agreeing to teach one play written by a woman playwright from history to my class, and, if I signed up, my students would be eligible to submit to the Judith Barlow Prize. If one of them won, they would get $2500—and I’d win $500. This got my attention, and I began signing up every semester.

I started by teaching Susan Glaspell’s brilliant 1916 one-act play Trifles, which was surprisingly effective in presenting the elements of dramatic writing I covered in class. My students’ work got better, but over time I noticed another shift. Every semester, I’d ask them how many women playwrights they could name. The first time I asked the question, most of my students knew of only a few, like Lillian Hellman and Lorraine Hansberry, and their limited knowledge didn’t seem to bother them. But, as the years have passed, I have noticed that even if my students can’t name many, they are aware that there are plenty of women playwrights, and they should know more of them.

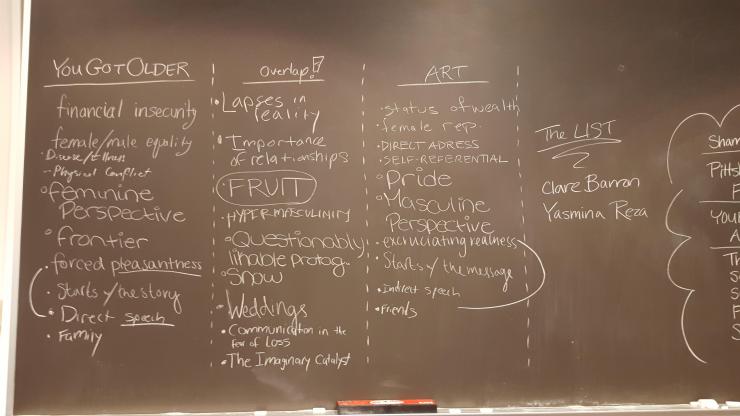

Last fall, when I asked the question to my students (full disclosure: these were the theatre majors), they filled up two dry-erase boards with the names of women playwrights they knew of or had heard of. We’re less than two years away from 2020, and though we aren’t likely to reach full gender parity by then, maybe something in the zeitgeist is moving us in the right direction?

The plan wasn’t to just blow the dust off old plays; Thorne hoped to connect young playwrights with these works, inspiring them to write their own equally powerful plays.

One Play at a Time

The mission of History Matters/Back to the Future is “to promote the study and production of women’s plays of the past in colleges and universities and theatres throughout the country and encourage responses to those plays from contemporary playwrights.” (Italics are mine.) The brainchild of Joan Vail Thorne, History Matters came out of a response to the 2009 Emily Sands Study at Princeton University, which examined gender bias in the theatre and confirmed discrimination against female playwrights. Thorne, a veteran regional theatre director, playwright, librettist, and teacher, came of age during the regional theatre movement, which, Thorne reminds me in our interview, was spearheaded by two women: Margo Jones and Zelda Fichandler. “Of course, everyone was enraged and sad,” Thorne told me, speaking of the study, “but we’d heard this before.” In 2002, Suzanne Bennet and Susan Jonas had conducted a study for the NYS Council of the Arts that had revealed the same profound disparity between professional productions written by men versus women on the American stage. Thorne was angry, but she didn’t want to wallow in it. “We were always lamenting,” she said, and her instinctive resistance to lamentation led her to seek out something to celebrate instead.

Thorne and her colleagues—academics and theatre artists—found plays, and a lot of them, written by women who’d been forgotten across decades and centuries. Thorne describes these writers as “young radicals, with tremendous passion,” who were writing plays that “even when they were commercial were about something important.” The plan wasn’t to just blow the dust off old plays; Thorne hoped to connect young playwrights with these works, inspiring them to write their own equally powerful plays. One Play at a Time was launched, and the competition’s prize—named after Judith Barlow, the editor of Plays by American Women, which reintroduced playwrights from 1900 to 1930s and again from 1930 to 1960s to the public—comes with a generous purse, signaling to young writers that their work is worthy of compensation.

In an effort to expand their reach, One Play at a Time’s database now includes a scenes library curated by acting professors, providing young actors with immediate access to the plays. A new grant this year, the Sallie Bingham Grant for two thousand dollars, will enable students to direct and produce a full production or series of readings of historic plays written by women, giving young theatre artists the tools to not only study but to perform and produce these works. Like the faculty incentive embedded in the Judith Barlow Prize, the Sally Bingham Grant, named for the prolific playwright, poet, and novelist, provides another five hundred dollars for a faculty mentor who will guide these student-driven projects.

On Her Shoulders

Another initiative that grew out of the Emily Sands Study, On Her Shoulders, was first conceived in 2013 by playwright Andrea Lepcio, performer Lillian Rodriguez, and Jonas, who co-conducted the 2002 NYS Study. This reading series of historic plays written by women began as a grassroots initiative, with Jonas guiding play selection. Together, they talked with actors and directors, found a location at the New School, and began hosting readings once a month, mostly out of a desire to know the plays better. Audiences were amazed by the breadth and quality of the work and the fact that they’d never heard of the writers showcased. According to Lepcio, the work they were uncovering gave her “permission as a playwright to go anywhere, say anything, [and] be true to [her] own vision.” Melody Brooks, artistic director of New Perspectives Theatre and cofounder of 50/50 in 2020, the grassroots movement towards gender parity in theatre, was brought on to curate the second year, and now New Perspectives has taken over in a more formal partnership with the New School, doing a reading series each year. Since then, Brooks has continued to branch out, going further back in history to find more undiscovered playwrights, including more women of color and from various cultures.

Audiences who attend On Her Shoulders readings tend to ask the question, “Isn’t it amazing that these plays exist?” But Brooks believes the question should be, “Why have we lost these plays in the first place?” Working to bring women’s historic writing to light is changing people’s minds not only about women in theatre history, but women’s place in history altogether. “We need a complete paradigm shift on how we view modern human [women’s] history,” says Brooks. “Because it’s all been a lie.” She continues, saying that women have always been doing everything, from writing plays to being rulers, doctors, philosophers, and soldiers. Despite their invisibility, they existed.

Going back to the past, however, is not the end goal. Like History Matters, Brooks is always looking for ways to get more young women involved. A primary focus of New Perspectives Theatre is their Women’s Work Lab, which develops eight to twelve new plays by women per year, from conception to the stage, during which Brooks insists on treating her young writers as professionals. She wants them to become champions of their plays so they can carve out their spots in future theatre history.

Working to bring women’s historic writing to light is changing people’s minds not only about women in theatre history, but women’s place in history altogether.

Closing the Gap

When playwright Whitney Rowland was a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University, she read a study first put out by the Dramatists Guild, now published in partnership with the Lily Awards, called the Count. The Count charts the disparity between men and women, as well as white writers and writers of color, breaking it all down into smaller and smaller slices of the American theatre pie. Rowland was horrified to learn of the 5:1 ratio of men to women on the American stage and, in response, created a course for undergraduates called Closing the Gap. The course, which she taught in 2016, was designed to reach soon-to-be fledgling theatre artists while they were still in school and show them how to replace the old canon with something new.

The main assignment was a group project. Using a regional theatre that failed the fifty-fifty “test” as their template, students had to essentially correct it by creating a season of six plays that fit the same parameters of the original season in terms of subjects, themes, genres, styles, time period, and more, except the plays had to be written by women. Rowland showed them how to find the work, starting with the Kilroy’s List and the New Play Exchange, and how to research and contact the playwright or her agent in order to secure the rights. Every week, Rowland began with a quiz, asking her students to list all the new writers they were learning about, practicing how to correctly spell and pronounce their names. She wanted her students to realize that the writers they were discovering were actually the playwrights who were going to help them make their careers as directors, actors, and producers. Invest in them, Rowland told her students, and they will ensure your future.

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

The homepage of History Matters is filled with photos of women’s faces, and as you click through more show up. These women are writers we may know, like Susan Glaspell of Trifles, and others we may not, like Rachel Crothers, who had thirty plays on Broadway, and Georgia Douglas Johnson, a poet, playwright, and pivotal figure in the Harlem Renaissance. There are forgotten playwrights whose works are now being revived, like Alice Childress’s 1954 play Trouble in Mind about racism in the commercial theatre—a play that could have been written yesterday. The faces take us far back in history to the likes of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the brilliant, self-taught philosopher, poet, and dramatist writing in Mexico in 1698, and even to Hrotsvitha, the first German playwright, writing in the tenth century—nullifying the belief that women weren’t writing plays that far back.

The rediscovering of so many important writers is exciting, but, at the same time, whenever another study emerges with depressing results, it forces us to wonder if we’re making any real progress. Participants of the History Matters program, like myself, are enthusiastic, but there are still a lot more people they need to reach. This year’s Judith Barlow Prize, for instance, had only twenty submissions—for a $2500 prize. Clearly, they need to get the word out. A winner and runner-up will be announced by the end of March—two more young playwrights inspired by those who came before them, who might someday be welcomed into a future canon. But will change happen one or two playwrights at a time, or will it come all at once, like a flood? Right now, it feels like there’s a lot of water building up behind that dam of history.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Congratulations to the Judith Barlow Prize Winners, Audrey Webb of Texas State University and runner up Hannah Manikowski of Carnegie Mellon University: https://www.eventbrite.com/...

Thanks. This really brings a lot of good information into one place. Appreciate it!

Cindy, I'm happy you found this useful. Feel free to share the information -- especially about the Judith Barlow Prize!

Thanks for sharing this Tammy. Well done!

Thanks David!

Thanks for this terrific article, Tammy! Here at CMU Whitney's brilliant course was one of many efforts to bring more female playwrights into the classroom and onto the stage - as well as concerted efforts to put more plays by non-white playwrights onto our syllabi and into our season. For example, in choosing the plays for this year's design 'collaboration project' the faculty made a commitment that 100% of the plays would be female-authored, and 50% by women of color. Your article is a good reminder that we can really make a difference from the classroom!

Thanks Wendy, glad to hear the work continues at CMU. I'd love to follow up with those students who were lucky to take Whitney's course in 2016 to see what impact it has on what they do in their careers.

Thanks for spreading the word about this program, Tammy. It is a terrific incentive. My student Lindsay Adams was an early recipient of the Judith Barlow Award for her play HER OWN DEVICES, inspired by the seminal play HARVEY, by Mary Chase. However, one drawback that I encountered is that their list of approved playwrights seems to end in the 50's. For example, I tried to make my students eligible by including a play by Wendy Wasserstein - but she was deemed too "modern" by the History Matters program. It doesn't seem quite right to me, to exclude a prominent woman playwright who won the Pulitzer Prize nearly 30 years ago and passed away at an early age. I would argue that there are several playwrights such as Wasserstein, who are historically significant even if their contributions are a bit more recent. I suspect that submissions for the Barlow Prize would increase if their approved list could be expanded.

Jon, you make a good point. I will leave it to the History Matters people to respond to why the 1950s seems to be the cut off right now (if that's still true?) It is true that we also need to remember playwrights from the more recent past, unless they slip into that forgotten history with the others from further back, and Wendy Wasserstein is certainly a significant playwright young writers should know.