Decolonizing Theatre/La Descolonización del Teatro

an Introduction/Introducción

This week we are holding space for a series on decolonizing theatre practice, which is not an easy thing to do. Instead of asking for single-narrative articles from multiple individuals, we have asked communities to have discussions and share them to keep the conversation around decolonization diverse and complex. Each piece is itself a conversation and we hope you'll join! We couldn't possibly cover everything, so please add your voice and perspective from wherever you sit/stand/breathe in the circle.—Madeline Sayet and Annalisa Dias, series curators.

Over the last year, the American theatre, like many other fields, has been looking at its roots and raising difficult questions. How could we as a field be guilty of so many instances of oppression, sexual harassment, and other forms of dehumanization despite increasing understanding of “equity, diversity, and inclusion” principles? What problematic systems did we step into and support that we may not even be aware of? Is there some invisible structure currently embedded in our institutions and the (inter)national theatre ecology?

This week, HowlRound is offering a series on Decolonizing Theatre Practice to increase basic understanding of how colonialism (still!) functions on these lands and across the globe. This series aims to create room for dialogue about how the “American” theatre has been and still is complicit in these systems, and also how it might be a space for needed healing.

We tend to think of colonization as a historical event, but…colonization is a structure, not an event. We can still see examples of classic colonial structure in many of the practices of our field.

You may have heard about the recent movement to decolonize the Brooklyn Museum and wondered what the implications might be for theatrical practice. Over the course of this week, we have invited a variety of artists to participate in a series of conversations about the way colonial structure inhabits our stories, our practice, and our communities, and to think about ways we might decolonize each and all of these. (As a note, each piece in the series has two or more voices as an intentional way to complicate the notion of a single narrator, even here on HowlRound.)

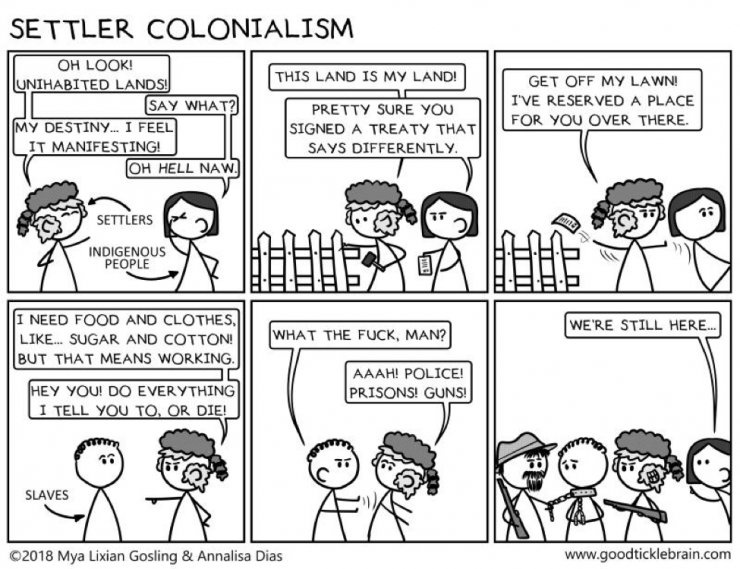

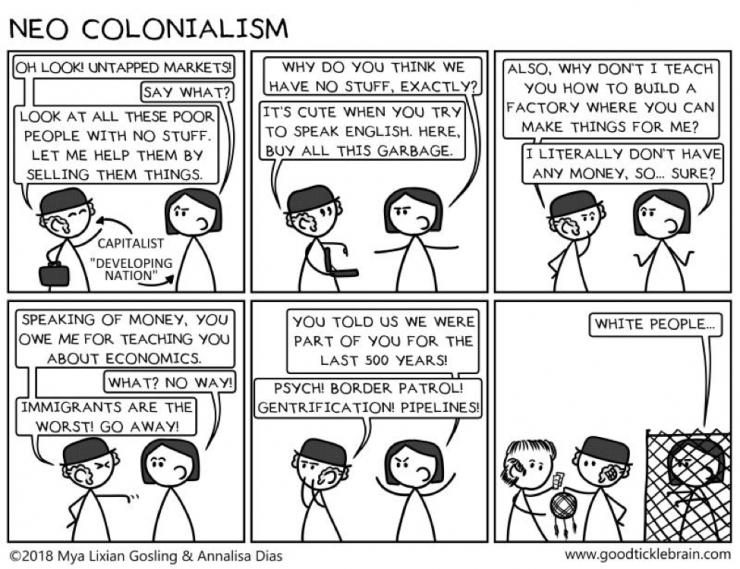

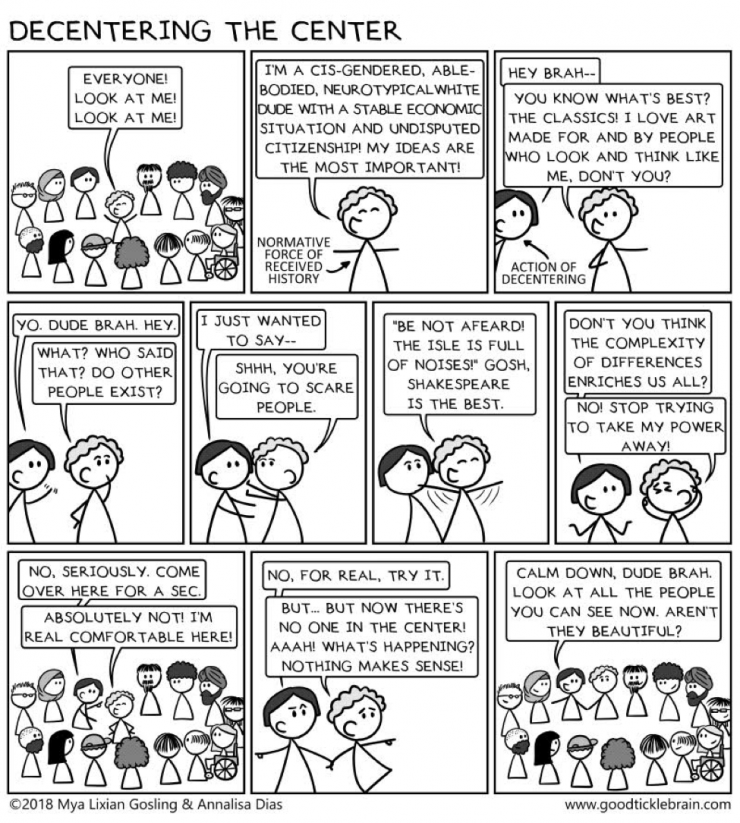

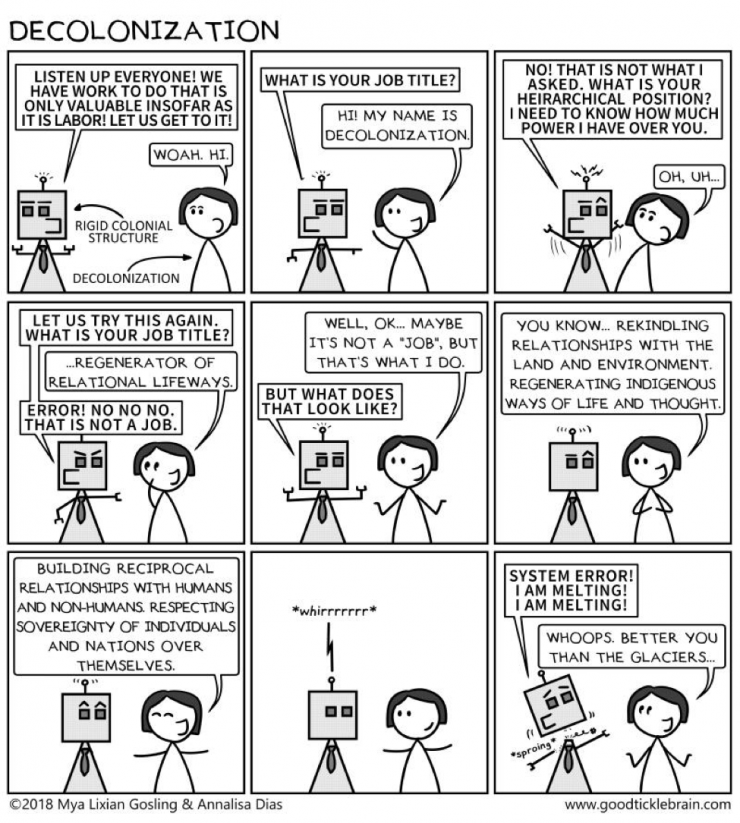

But first, what is colonialism anyway? We have invited Shakespeare cartoonist Good Tickle Brain (Mya Gosling) to collaborate with playwright Annalisa Dias to help us understand the structures and vocabulary around decolonization. For anyone interested in a more thorough set of definitions, check out this handout created by Claudia Alick, Ty Defoe, Annalisa Dias, and Larissa FastHorse for their “decolonizing theatre practice” session at the 2017 TCG conference.

The structure of classic colonization, typically characterized by a mother country that enters into an extractive and genocidal relationship with what becomes a colony, is usually what people think about when they hear the word “colonialism.” We tend to think of colonization as a historical event, but many, many theorists have written about how colonization is a structure, not an event. We can still see examples of classic colonial structure in many of the practices of our field.

Some examples for further discussion might include:

- Prominently funding the use of Shakespeare in educational programming for “at-risk” populations, based on the notion that Shakespeare will “improve” people. This has been termed by Dawn Monique Williams and others as “The Shakespeare Missionary Complex.” While well-intentioned, this unfortunately mirrors practices of missionary conversion: the idea that bringing this famous white author to people of color improves their lives perpetuates the idea that one culture is superior to others.

- Educational theatre programs in “at risk” or “underdeveloped” neighborhoods. (These words are usually coded language for communities of color, which are positioned as in-need-of-saving. How might we critique and decolonize these power dynamics?)

The structure of settler colonialism, which grows out of classic colonialism but is characterized by the colonists staying rather than returning to the mother country, relies on the erasure of Indigenous peoples and conversion of people (of color) and lands into property. The US, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia are considered settler colonial societies.

Some examples of settler colonial structures in theatre include:

- The fact that very few theatre institutions have produced native plays or have reciprocal relationships with Indigenous artists and the lands on which theatres operate.

- The commodification of “equity, diversity, and inclusion” initiatives (think about the ways in which black and brown bodies are commodified in the name of “diversity”).

- Beyond individual institutions, think about the rhetoric of Creative Placemaking, Creative Cities, and Arts Districts and their relationship to gentrification/displacement of primarily communities of color. How does this dynamic mimic settler colonial structure?

Neocolonial structure, typically characterized by an economic system that mimics classic colonization with the mother country repositioned as a “first world” nation and colonial countries as the “developing world,” also persists in the international theatre ecology. Neocolonialism is also characterized by the extractive commodification of lands and by cultural appropriation, specifically insofar as profit can be made by selling cultural products extracted from “developing” countries.

Some examples of neocolonial structure in theatre include:

- International arts partnerships that assume dominant Western stories and theatremaking have anything to do with “saving” or “developing” other communities.

- The role of exporting US cultural products in the service of global US imperialism.

- Funding structures that rely on extractive technologies (many theatres accept corporate funding from or have investments in the fossil fuel industry).

- Predominantly white institutions receiving funding and prestige for “equity, diversity, and inclusion” work while theatres of color continue to receive disproportionately low funding.

- In season planning, the economic quantification and tokenization of “identity” plays (ie. having a “Black play” or a “Latinx play,” etc).

Decentering is one of many strategies for moving toward decolonization. As we saw above, classic colonial structure presumes that the “mother country” is the “center” toward which all things flow and from which all things come. This is one version of history that has been systematically centered over time. Decentering opens space in the circle so all can be heard and seen. If we acknowledge the circle we stand in with everyone else (human and more-than-human), it will be easier to connect and learn. Decentering involves understanding that there are many models for story, narrative, and leadership. For example, many traditional Indigenous leaders take the entire group into consideration in decision-making, rather than using hierarchical (colonial) decision-making processes where individuals function on their own and report back (to the center!). Decentering helps us remember that our communities are healthier when every voice is in the circle with us.

Some examples of decentering questions we might ask include:

- What assumptions do I make in meetings, collaborative processes, and other decision-making spaces about whose opinions are most valid? What are my implicit biases?

- What is the structure of a play and the way it is cast? Who has the most stage time? What character is most often speaking? Are there other ways to rethink whose story is being told and how?

- When I find myself in the center, how do I step out and offer space to others? How can I listen better? If my or my community’s voice has been systematically silenced, how can I work to center that narrative?

- How does my work or my institution center capitalist cis-heteronormative ableist white supremacy? How can I or my institution decenter those and center voices and bodies that have historically been silenced and/or erased?

There are many strategies for decolonization. Most of them have to do with rekindling relationships to the land, pausing the cycle of production to create space for listening, and decentering white supremacy and its need for strict boundaries, borders, and binaries.

Some questions we all might ask ourselves on our decolonial journey are:

- What is my relationship or my theatre’s relationship to the lands and Indigenous territories I live and work on? What degree of reciprocity is there? How can I begin to acknowledge and build reciprocal relationships with Indigenous peoples where I live and work?

- How is my work or institution complicit in colonial structures and how might we interrupt and reimagine those structures?

- How does my work or my institution participate in environmental harm?

This week, we’re excited to go on a decolonizing journey and we can’t wait to dialogue as an interconnected field about the ways we might all move forward together. We’ll start with a conversation about decolonizing the primacy of text, words, and language. Then we’ll move into a conversation about decolonizing creative processes. Next, we’ll hear from a variety of folx about decolonial ethical principles for working with/in communities. Then we’ll broaden the perspective beyond Turtle Island and think about representation, borders, and identity in an international context. Finally, we’ll get together again for a live conversation about interconnected theatre ecologies.

Questions that may come up this week:

- What are the ways we colonize our audiences, our artists and ourselves?

- How can we dismantle these faulty principles and offer new solutions to connect to the community and land we are a part of?

- How often do you think about where you’re from? The waterways giving life to the land around you? What are your roots? Your community? Where do you connect?

We hope that each piece in this series will end with more questions than answers, and we hope you’ll use the comments to engage in dialogue around the many ways that colonial structures manifest in our theatre spaces and processes. In that spirit, we invite you to name, reflect on, and make visible other instances (in your own practice or in your community) where you’ve observed colonial power dynamics at work.

***

En Español:

Esta semana seremos anfitriones de una serie de artículos sobre la descolonización en la practica teatral, tema cual no será nada fácil. Nuestra meta es la de alejarnos de la narrativa de un solo individuo y en ves comisionar aquellas escritas por varios individuos. De esta forma, pedimos a una serie de comunidades que se involucraran en estos temas y que compartieran sus conocimientos con tal de otorgarle la diversidad y complejidad necesaria a las conversaciones sobre la descolonización. Cada articulo en esta serie es en si una conversación a la cual esperamos que usted, lector, también se le una. No es posible cubrir todos los temas, así que por favor únase y dele voz y perspectiva a esta conversación desde donde usted se encuentre. —Madeline Sayet y Annalisa Días.

Durante el ultimo año, el teatro norteamericano, igual como muchos otros campos, han observado cuidadosamente sus raíces y a la ves, han planteando preguntas difíciles sobre estas raíces. ¿Cómo es que nosotros los del mundo artístico también hemos sido culpables de tantos casos de opresión, acoso sexual, y otras formas de deshumanización cuando a la vez nos decimos conocer bien los principios de la “equidad, diversidad, e inclusión”? ¿Cuáles son aquellos sistemas inevitablemente problemáticos cuyos hemos heredado y a los cuales seguimos apoyando, tal vez sin darnos cuenta? ¿Existe aquella estructura invisible que actualmente forma parte del tejido organizacional de nuestras instituciones y por ende forma parte del ecosistema teatral internacional?

Esta semana, Howlround ofrece esta serie sobre la descolonización en la practica teatral con tal de incrementar nuestro conocimiento básico de cómo es que el colonialismo (¡aun!) funciona en nuestro país y en el resto del mundo. Por medio de esta serie esperamos crear espacio para que se forme un dialogo sobre la complicidad del teatro norteamericano, e igualmente podamos sanar y recapacitar juntos.

Recientemente se dio a cabo un empeño para descolonizar el Museo de Brooklyn. Naturalmente, es imposible no pensar en las implicaciones que tuvo este empeño en nuestras practicas teatrales. Durante el curso de esta semana, invitaremos a una variedad de artistas a ser participes en esta serie de conversaciones sobre las muchas maneras en las que la estructura colonial habita en nuestras historias, nuestra practica, y en nuestras comunidades, y a pensar en maneras en las que podamos descolonizar cada una de ellas. (Vale notar que cada articulo de esta serie contiene mas de dos ‘voces’ de forma intencional con tal de texturizar la noción del autor singular por medio de HowlRound.)

Pero primero que nada, ¿a que nos referimos con el colonialismo? En este articulo, invitamos a la caricaturista Shakesperiana Good Tickle Brain (Mya Gosling) en colaboración con la dramaturga Annalisa Días a ilustrar las estructuras y el vocabulario al que nos referimos cuando hablamos de la descolonización. Para aquellos interesados en una definición mas directa, léase aquí este folleto creado por Claudia Alick, Ty Defoe, Annalisa Días, y Larissa FastHorse, cual fue creado como parte de su sesión en la conferencia TCG 2017 llamada “descolonización en la practica teatral.”

La estructura de la colonización clásica, típicamente caracterizada por una madre patria (o el país natal), cual al entrar a un estado extractivo y de genocidio con otra tierra, la convierte en su colonia, es usualmente en lo que pensamos al escuchar la palabra “colonización.” Solemos caracterizar a la “colonización” como un evento histórico, pero son muchísimos los teoristas que han escrito acerca de cómo la colonización en una estructura, y no un solo evento histórico. Podemos observar en la actualidad varios ejemplos de cómo las estructuras de la colonización clásica se manifiestan en varias áreas de practica en nuestro campo.

Algunos ejemplos incluyen:

- El abundante apoyo financiero ante el uso de los programas educacionales basados en Shakespeare para las comunidades “en riesgo,” basada en la noción de que Shakespeare “mejora” a las personas. A este fenómeno se le ha denominado el “Complejo Misionero Shakesperiano” por parte de Dawn Monique Williams y varios otros. Aunque bien intencionado, esta práctica desafortunadamente imita a la de los misioneros religiosos en busca de la conversión religiosa: la idea de que al brindarle conocimiento a este famosísimo autor blanco a las comunidades de color las mejorará automáticamente perpetúa la idea de que una cultura (la blanca) es superior a la otra.

- Los programas educacionales en las zonas “en riesgo” o en “subdesarrollo.” (Estas palabras son comúnmente usadas como idioma código para referirse a las comunidades de color, cuyas se les posiciona como aquellas con necesidad de ser rescatadas. ¿Cómo podemos darle giro decolonial a estas dinámicas de poder?)

La estructura del colonialismo de los colonos, naciente del colonialismo clásico pero caracterizado por los colonizadores que se quedan en vez de regresar a su país natal, depende de la eliminación de las razas indígenas y de la conversión religiosa de las personas (de color) y la conversión de las tierras en propiedades. Los Estados Unidos, Canadá, Nueva Zelanda, y Oceanía (Australia) son consideradas sociedades con estructuras del colonialismo de los colonos.

Algunos ejemplos de estas estructuras en las practicas teatrales incluyen:

- El hecho de que muy pocas instituciones de teatro producen obras sobre las personas de raíces nativas o tienen relaciones reciprocas con sus comunidades indígenas o con las tierras en las que estas instituciones se manejan.

- La mercantilización de las palabras “equidad, diversidad, e inclusión” y sus iniciativas (piense en las varias formas en las que las personas de color son mercantilizadas en el nombre de la “diversidad”).

- Mas allá de las instituciones individuales, piense en la retorica detrás de las ideas como las de Lugares Creativos, Ciudades Creativas y Distritos Culturales y su relación al aburguesamiento/elitización residencial primordialmente de las comunidades de color. ¿Cómo es que esta dinámica imita la estructura de la colonización del colono?

La estructura neo-colonial, típicamente se caracteriza por un sistema económico el cual imita a la colonización clásica, pero con la patria natal reposicionada como nación “primer mundista” y a los países colonos como el “mundo en desarrollo” (o tercer mundista); un sistema cual también se nota de forma persistente en el ecosistema del teatro internacional. El neo-colonialismo es también caracterizado por la mercantilización de los sistemas extractivos de las tierras y por la apropiación cultural, específicamente con fines de lucro, es decir que se puedan vender los productos culturales extraídos de los países “en desarrollo”.

Algunos ejemplos de las estructuras del neo-colonialismo en el teatro incluyen:

- Cualquier asociación internacional que asume que las narrativas occidentales y el teatro proveniente de estas brindan “la salvación” o el progreso ante comunidades “en desarrollo.”

- El hecho de la exportación de productos culturales estado unidenses que llevan como fin servir al imperialismo global por parte de los EUA.

- Brindar apoyo financiero a las instituciones o estructuras dependientes de compañías que ejercen la tecnología extractiva (varios teatros aceptan donaciones corporativas de parte de, o tienen inversiones en la industria del combustible fósil.)

- Las instituciones primordialmente blancas cuyas reciben dinero y son galardonadas por su trabajo entorno a la “equidad, diversidad, e inclusión” mientras que los teatros de y para las personas de color continúan sin recibir el mismo apoyo.

- A la hora de la planificación de la temporada, la cuantificación económica y la tokenización de las obras de "identidad" (es decir, tener una obra “negra" o una obra “Latinx", etc.).

La descentralización es una de muchas estrategias para comenzar la descolonización. Como antes dicho, la estructura colonial clásica posiciona al país natal en el “centro,” en aquel lugar del cual toda cosa va y viene. Esta es solo una versión de la historia y aquella que ha sido sistemáticamente centralizada durante nuestros tiempos. La descentralización, en este sentido, abre el espacio de aquel circulo imaginario con de que todos los presentes sean escuchados y vistos. Si le damos reconocimiento al circulo, nos situamos junto con todos los demás (humanos y mas-que-humanos), y de esta forma se nos hará mas fácil conectar y aprender uno del otro. Descentrar el centro significa entender que existen muchos tipos de historias, narrativas, y liderazgo. Por ejemplo, varios lideres tradicionales de raíz indígena toman en cuenta a su circulo y al grupo entero a la hora de tomar decisiones en vez de usar el sistema jerárquico (colonial) para tomar decisiones en el cual los individuos actúan por su propio acorde y luego reportan sus decisiones al grupo (¡al centro!). El descentrar nos recuerda que las comunidades sanas son aquellas en las que toda voz del grupo o circulo se incluyen.

Algunos ejemplos de preguntas sobre la descentralización que nos puedan ayudar incluyen:

- ¿Qué suposiciones hago durante juntas, procesos colaborativos, y otros puntos de tomar decisiones sobre las opiniones que mas valen? ¿Cuáles son mis prejuicios implícitos?

- ¿Cuál es la estructura de una obra y la forma en la que se elije el elenco? ¿Quién toma la mayor parte del montaje? ¿Cuál personaje tiene la mayoría de las líneas? ¿Existen otras maneras de pensar de quien es la narrativa que estoy contando y como hacerlo?

- Cuando me encuentro en el centro, ¿Cómo es que me posiciono como parte del circulo para darle lugar a otros? ¿Cómo es que puedo aprender a escuchar mejor? Si mi voz o la de mi comunidad es aquella que a sido sistemáticamente silenciada, ¿cómo es que le puedo dar enfoque a esa narrativa?

- ¿Cómo es que mi trabajo o el de mi institución le da el centro a los sistemas capitalistas, heteronormativos, y de supremacía blanca? ¿Cómo puedo yo o mi institución descentrar a estos y centrar en vez a las voces y los cuerpos de aquellos que históricamente han sido silenciados o erradicados?

Existen varias estrategias para la descolonización. Muchas de ellas tienen que ver con reavivar nuestra relación con la tierra, darle pausa al ciclo de la producción con tal de darle lugar al saber escuchar y descentrar la supremacía blanca junto con su ideología de crear barreras estrictas, fronteras, y a sistemas binarios.

Algunas preguntas que nos podemos hacer en nuestro peregrinaje ante la descolonización son:

- ¿Cuál es mi relación, o la de mi teatro, con las tierras y los territorios indígenas en los que vivo y trabajo? ¿qué grado de reciprocidad existe? ¿Cómo es que puedo comenzar a reconocer y a construir relaciones reciprocas con las personas indígenas de los lugares en los que vivo y trabajo?

- ¿Cómo es mi trabajo o institución cómplice en las estructuras coloniales y como podría interrumpir y volver a imaginar o reinventar esas estructuras?

- ¿Cómo es mi trabajo o institución partícipe en los daños hacia el medio ambiente?

Compartimos nuestra emoción durante esta semana al embarcar sobre este peregrinaje ante la descolonización y esperamos con emoción el dialogo que surgirá en este campo tan conectado sobre las varias formas en las que, unidos, podamos avanzar a un mejor futuro. Empezaremos con la conversación sobre la descolonización del texto, las palabras, y el lenguaje. Después, empezaremos a conversar sobre como descolonizar el proceso creativo. Siguiente, escucharemos sobre los principios éticos para trabajar con/ y entre varias comunidades. Seguiremos con avanzar la perspectiva mas allá de la Isla Tortuga (Norte América) y pensaremos acerca de la representación, las fronteras, y la identidad en un contexto internacional. Finalmente, nos uniremos en conversación en vivo sobre la interconectividad del ecosistema teatral.

Las preguntas que puedan surgir esta semana incluyen:

- ¿De que manera(s) colonizamos a nuestro publico, a nuestros artistas, y a nosotros mismos?

- ¿Como podemos desmantelar estos principios erróneos y ofrecer soluciones hacia la conexión entre la comunidad y la tierra de la cual somos parte?

- ¿Qué tan seguido pensamos sobre nuestros orígenes naturales? ¿Sobre los ríos y cuerpos de agua que nos brindan vida a nosotros y a lo que nos rodea? ¿Cuáles son nuestras raíces? ¿Las de su comunidad? ¿En donde se conectan unos con otros?

Esperamos que cada articulo en esta serie brinde mas preguntas que respuestas, y esperamos que los lectores utilicen el área de comentarios para unirse al dialogo sobre las varias formas en las que las estructuras coloniales se manifiestan en nuestros espacios y procesos creativos. Dicho esto, les invitamos a compartir otros momentos (personales o como miembros de su comunidad) en los cuales se ha observado la dinámica de poder de las estructuras coloniales, ya sea en su practica individual o trabajo artístico.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

As a cis white lady theatremaker/educator who is committed to doing work for social change, I want to admit that found myself having a lot of initial reactions of, like “pinch,” “ouch,” etc - realizing that I am complicit in many of these practices, but then also having that impulse to resist, to “throw up my hands,” or wish that there was the voice of the “devil’s advocate” represented more. But I am proud that with each of those reactions, I was able to breathe and try to step back and just listen, reflect, and accept that there is so much truth here and that there is so much implicit bias not only in the content of my work, but also in the *way* I work. I feel a little like the dude brah in the de-centering cartoon, maybe, and I really appreciate the sentiment of that one - the idea that we can be uncomfortable, but if we have the courage to step out of the center and work with our own discomfort, there is so much beauty (and truth!) to be seen. So I want to say thanks to the folks in this series for being the the lady in the de-centering cartoon (and all the cartoons) for taking the time and energy to do this article and this series. I am excited to read the rest. Thank you!

Hi Jane, Thank you for this insight! I think you're super not-alone here. I've heard very similar things from a bunch of folx about leaning into the discomfort and being able to find the beauty. Madeline and I did a session on decolonizing Shakespeare at the Shakespeare Theatre Association conference this year, and there were similar points raised. I'm always inspired when people are brave enough to name the discomfort publicly. You know? We're in it together. Thank you for sharing your perspective!