The Collaborative Possibilities of Mediaturgy

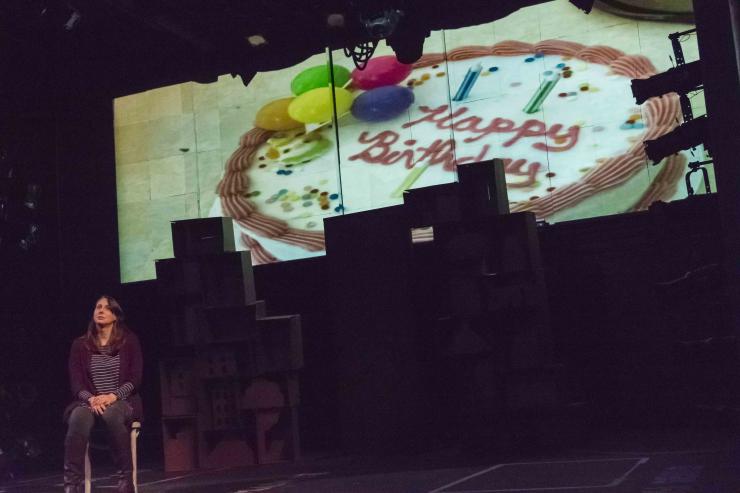

In the typical process of new play development, a script is delivered to designers a few months (at best) before opening; lighting, sound, and costume may spend some time working with the playwright, but ultimately, directors often influence much of the design. But for a production of Jennifer Barclay’s Ripe Frenzy, which was awarded the National New Play Network’s Smith Prize for Political Theatre, a unique collaborative process between playwright and projection designer Jared Mezzocchi allowed a close and ongoing dialogue between the two artistic positions. This made it possible for Ripe Frenzy, which I saw at New Rep Theatre in Boston in March 2018, to represent a complicated and often unheard perspective from the myriad narratives that surround gun violence in the United States: the perpetrator’s family.

Barclay and Mezzocchi, who are both Assistant Professors in the University of Maryland’s School of Theatre, Dance, & Performance Studies Program, started their collaboration on Ripe Frenzy by asking questions about how the media affected and perpetuated mass shootings. Their early conversations created points of origin for both playwright and designer: Mezzocchi’s projections would function as any character in a play, with defined wants and needs that became part of the behavior of the piece and that demonstrated a clear dramatic arc. Mezzochi calls this process “mediaturgy,” and it is this collaborative technique that makes the play’s nuanced approach to mental illness and gun violence possible.

Ripe Frenzy takes place in the aftermath of a horrific shooting that occurs during the third act of fictional Tavistown High School’s annual production of Thornton Wilder’s meditation on life and death, Our Town. The narrator, Zoe, a self-proclaimed “town historian,” takes on the role of Wilder’s Stage Manager, and leads the audience through her past memories and present revelations to detail events leading up to and following the event. The audience learns that the shooter, who remains nameless and faceless throughout the play, is in fact Zoe’s son. She grapples with the reality that her son, her “Bright Eyes,” was both a beloved child and wrought appalling violence on the town in which she herself grew up. As the final line of the play says, “both things are true.”

Mezzocchi’s projections would function as any character in a play, with defined wants and needs that became part of the behavior of the piece and that demonstrated a clear dramatic arc.

Barclay chose Our Town as an anchor for Ripe Frenzy because mass shootings have become, sadly, a quintessentially American experience; she was interested by the juxtaposition between the youth and vibrancy of Grover’s Corners and Tavistown, New York and the stark reminder of mortality that descends on both communities.

These initial ideas developed over the course of a series of workshops and productions supported by National New Play Network’s funding structure, which not only provided support for Barclay, but also coordinated a Rolling World Premiere at member theatres across the country. Ripe Frenzy was workshopped at Woolly Mammoth and the Ojai Playwright’s Conference under the direction of Margot Bordelon. Barclay expressed how Bordelon made herself “intensively available” during each workshop, helping Barclay explore changes to the script, and bringing her “smart dramaturgical mind” into the workshop environment.

Later in the process, Ripe Frenzy was selected for the first collaborative workshop between NNPN and PlayPenn; the two organizations assembled a cast and director to develop the project alongside Barclay prior to the official start of rehearsals at New Rep. NNPN and PlayPenn’s efforts made it possible for other important collaborators to be in the room: Michele Volansky, the Associate Artistic Director of PlayPenn served as dramaturg, the design team for the New Rep production was also in attendance, and Rachel May, who would later direct the production at Synchronicity Theatre in Atlanta, all provided space for Barclay to “push the boundaries of [her] work.”

Collaboration with new directors continued with full productions in March 2018 at New Rep with Bridget Kathleen O’Leary directing; in April, Synchronicity Theatre in Atlanta produced the piece with Rachel May at the helm; and in May Greenway Court Theatre in Los Angeles premiered the piece, directed by Alana Dietze. Barclay commented that each of these collaborations brought new ideas and interpretations to the table. What remained consistent throughout all the collaborative moments, however, was Barclay and Mezzocchi’s commitment to the connection between the design and the script.

The play opens in darkness. The first light the audience sees is the red glow from a GoPro camera that sits atop a man’s head, just before he disappears again. Zoe charges after him with a flashlight but is too late to catch up. She turns to the audience and begins her opening monologue. Complete with latitude and longitude coordinates, Zoe recounts the history of Tavistown. The New York equivalent to Grover's Corners puts on a yearly production of Our Town at the local high school. She and her best friends, Felicia and Miriam, were all part of the production when they were at Tavistown High, and now their children—Zoe's son, Felicia's son, Matt, and Miriam's daughter Hadley—are following suit.

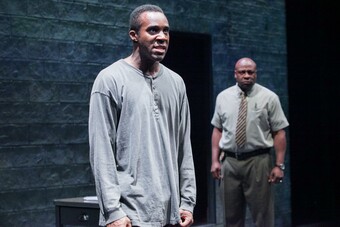

As Zoe narrates, a projector suddenly casts an image of a “shadowy forest, a little menacing” onto the backdrop behind her. This sudden and disturbing appearance of the forest is our first introduction to Zoe’s unnamed son. Zoe locates him for the audience at the back of the house, at the tech booth. He created the scenery for the production—beautiful images that enhance the fictional world of Grover’s Corners —but was not cast alongside Matt and Hadley. Furthermore, the audience learns he is not attending the prom alongside his friends, as was always the plan for these former "Three Musketeers." His social position, it seems, had changed in the months leading up to the shooting. But rather than representing Zoe’s son as an embodied character, and before Zoe reveals the truth of his own crime, the audience meets Bryan James McNamara, a seventeen-year-old high school student who carries out a school shooting and films it using a GoPro camera. The details of his crime emerge during the preparations for Our Town, ceaselessly pushed to character’s cell phones in a series of “ping” notifications.

Over time, the news media has codified the personality traits and personal circumstances of mass shooters, even though neither psychologists nor law enforcement have been able to offer a definitive profile: a white male, he is usually categorized as a loner with a violent past, and perhaps a history of mental illness. He idolizes his predecessors, looking to past crimes as inspiration for his own. Most importantly, the shooter wants to make a mark on society through violence. He wants his name to be known, even infamously. In Ripe Frenzy, both McNamara and Zoe’s son represent this figure, but the play’s mediaturgy provides a more nuanced interpretation. The audience learns about his childhood, his relationships, and his emotions through the images projected—in the Boston production—on three large screens around the theatre. His character remains in continuous dialogue with his mother as she tells the story. The images give a voice for the nameless and faceless antagonist.

Barclay's text and Mezzocchi's projections were in dialogue throughout 'Ripe Frenzy,' seamlessly supporting each other while telling a powerful story about the complexities of violent acts.

Barclay and Mezzocchi use McNamara as a simulacrum for Zoe's son and his own crime. Zoe is unwilling and perhaps unable to recount the details of what happened on the day of the shooting in Tavistown, but she confronts McNamara in a scene that allows her to fantasize what she might say to her son if only he were there. Mezzochi's projection work here depicts him as trying to antagonize Zoe, attempting to remind both her and the audience of his terrible actions as she struggles to advocate for him in multiple scenes that represent their past relationship. As McNamara and her son's crimes weave in and out of the narrative, Zoe fiercely clings to both the happy memories of her son and how she tried to raise him "to see the beauty in life," despite the images that seem to contradict her hopeful memories.

The audience's final interaction with Zoe's son comes in the last moments of the play when the audience learns what happened on the opening night of Tavistown's Our Town. In this moment, the mediaturgy of the piece reaches a dramatic climax. As Zoe, Miriam, and Felicia reenact squeezing into the tech booth to watch the performance, the GoPro video shows Zoe's son's final trip backstage cutting out just before the shooting begins. This perspective, supported by the design and the text, allows the audience to see what he sees. After nearly eighty minutes of this character making his feelings and motives known through image, it is almost as if he is finally speaking in these last moments, even though the film is silent.

Barclay's text and Mezzocchi's projections were in dialogue throughout Ripe Frenzy, seamlessly supporting each other while telling a powerful story about the complexities of violent acts. What made this exchange possible was their close collaboration from the project's inception, and the support from the National New Play Network that allowed their partnership to continue. While both had invaluable "dark time" during which they worked independently, they also shared a vision and concept for telling the story. The play, then, represented a narrative about mass shootings that lent considerable nuance to a trope perpetuated by the media. The perpetrators of these violent acts all belong to someone and live somewhere, even if those relationships have broken down or changed over time. The shooter can be mourned, and the mourning can be not only for their act, but also for the way their act affected the life of those left behind. A killer can be loved. Both things are true.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I really enjoyed this show when it was in Boston. Thank you for covering it!

Any chance of crediting the actor and other designer’s work who appears here?

Thanks for bringing this to our attention. We've updated the piece. Hope you enjoyed the article!