The spectrum of eating disorders is varied; they manifest in a myriad of ways and with a variety of symptoms in addition to emaciation. Unintentionally, this singular representation re-enforces a cultural misunderstanding about eating disorders. For example, when I ingested stories such as Cassie’s from Skins or Ellen’s from To The Bone, my pre-recovery brain processed something even more insidious: I mustn’t have a real problem, because I don’t look “sick enough.”

For Food Fight, the play I was working on, it was imperative that the plot would provide impetus for several disordered patients to interact. These patients would have varying presentations of the disorder, offering points of comparison and similarity, which would allow me to focus on accurately presenting the broadness of the spectrum so that someone at risk might have the opportunity to reflect on their relationship with their own body. Complexity and accuracy were the overarching goals—as much as is possible without reducing the characters to a list of symptoms in a one-act show.

Emily and I began our development journey by consulting an organization called the Butterfly Foundation, one of Australia’s foremost eating disorder support foundations. They oversaw the development questionnaire, which was passed on to young people in various stages of recovery. This questionnaire was designed to understand the emotional realities of the young people’s experience with the disorder and their hopes regarding shifts of public understanding. With this material and my own recovery journey as a starting point, I began writing. Once the draft was created, we needed to approach the next hurdle: casting.

Complexity and accuracy were the overarching goals—as much as is possible without reducing the characters to a list of symptoms in a one-act show.

A Medium Problem

When we talk about eating disorders on stage and screen, we’re often ignoring an elephant in the room: our industry is one of the worst for incidences of diagnosed and undiagnosed eating disorders. Actors, crew, and audience members are at risk—all groups are at the mercy of a machine that reports to a culture of impossible beauty standards.

Almost no one is immune from the beauty-centric pressures of our Western society (a firmly accepted precursor for the onset of an eating disorder), but the risks are especially high for young people, trans people, and female—and increasingly male—performance professionals. The environment in which we are expected to work does not protect us or provide a healthy foundation with which to view our physical form.

For performers, the physical form is regarded as public property, a canvas that must report to a slew of other creatives. In no other profession would there be a formal expectation that employees or volunteers alter their physical appearance in order to do their job. Professional chameleons, actors are expected to change their physical appearance in pursuit of “realism” at best and “cultural ideals” at worst.

The industry-accepted “necessity” of physiological flexibility is publicly endorsed with celebrities candidly citing the help of various weight-loss specialists in public forums whenever their projects seem to demand it. The presence of psychological support networks is deafeningly absent from the public discussion; this absence is felt in casting rooms, rehearsal rooms, and post-show foyers. We tacitly accept the reality that our relationship to our bodies is not protected.

Performance works that portray the experiences of people whose bodies are in extreme distress potentially endanger actors even further: if a character is anorexic, an audience member may, subconsciously or consciously, think, That actor doesn’t look sick enough, or, God, that actor probably is anorexic. The suspension of disbelief can only protect an actor for so long; their body may “belong” to the character psychologically inhabiting it, but it first and foremost belongs to them, even when the audience believes it is the property of a fiction.

With actors who are willing to engage in body alteration (Lily Collins is a prime example; she famously returned to an anorexic physicality for her role in To The Bone despite suffering the disease previously), the risk of a negative psychological impact is significant. For our play, Emily and I asked ourselves, “How can we protect our actors without compromising on authenticity or clarity in our storytelling?"

Safe Practice

We explicitly enlisted performers who were able to safely engage in the topic: open calls to actors within our social media networks allowed actors to approach us. Inevitably, a huge number of these people had an interest because they had experienced body-image related challenges either first- or secondhand.

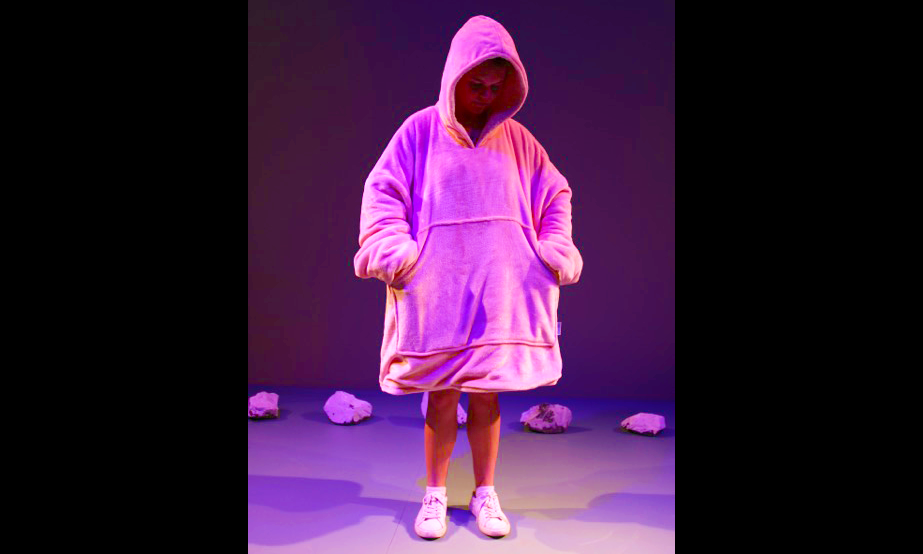

We also devised a way to subvert the expectation that the audience should have access to the actors’ bodies at all; the plot justified them covering up in costumes that were comically large and form-obscuring. By disrupting visual access to the actors, we negated the pressure for them to pursue physiological realism and invited audience members to investigate eating disorders on a different level.

But, even with the actors protected, there was another reality to confront: a visual medium that mishandles this complex topic can achieve the opposite results of the prevention it sets out to achieve.

“How can we protect our actors without compromising on authenticity or clarity in our storytelling?”

Contagion

One of the key dangers of a shock-tactic approach is the risk of unintentionally inducing copycat behavior in vulnerable audience members.

Plays that depict or describe acts of self-abuse such as binging, purging, or starvation in explicit detail—and featuring emaciated figures in the pursuit of authentic “grittiness”—unintentionally provide at-risk viewers with a “how to” manual. Vulnerable viewers may subconsciously store away the things they view, only to have their unwell brain present this behavior as a misguided “solution” in moments of emotional vulnerability or distress.

We know that when the media explicitly depicts self-harm there are spikes in occurrences in the real world, especially amongst young people. Media contagion effect is an observable, well-studied phenomenon in which “the relative risk of suicide following exposure to another individual’s suicide was 2 to 4 times higher among 15- to 19-year-olds than among other age groups.” However well-intentioned they are, high-impact visuals and “explicit” demonstrations of binging, purging, and starving could increase the risk of a ripple effect—and, according to some studies, an estimated 20 percent of females have an undiagnosed eating disorder.

Far from a simple discomfort-based objection, “triggering” speaks to a moment, object, or scenario that provokes an involuntary emotional and physiological reaction in people with past associations with trauma or disorder. This person might then feel the impulse to engage in faulty coping strategies associated with their disorder, rendering our efforts to create a preventative work null and void.

While it’s impossible to control what triggers us, or adequately anticipate all of the things that may trigger a viewer, we felt we had to try for our project. The first step was to necessitate through the plot that all characters were prevented from describing or enacting behaviors related to their disorder.

The discussion (and in some cases frustration) around the use of trigger warnings in theatre is a salient moment to assess our intention as makers: in our case, minimizing triggers was an act not of political correctness or box ticking but one of politically engaged compassion. Far from rendering the subject inert or sterile, we could use the opportunity to provide a safe space to engage with a potentially dangerous subject.

As theatremakers, it is our job to frame eating disorders compassionately, to create an environment that’s free from judgment and that’s instead full of empathy.

Reframing the Disease

The word obscene derives from the Greek word obskene. Translated, it means “behind the backdrop,” deriving from its use in the staging of ancient Greek plays. Moments of intense violence or mutilation were not erased from our plot, they were simply kept off stage—referred to but not seen. The focus then shifted from the brutality or the severity of the acts themselves to the emotional impact of these moments afterwards or before.

The ways in which I used food as a coping mechanism was the least interesting element of my disorder: the issues below the surface, such as with control, comparison, denial, secrecy, and conflict avoidance, were far more compelling. What is interesting about these behaviors is that they are universal, and focusing on what’s universal about coping mechanisms rather than what’s specific or scary about eating disorders sheds new light on an otherwise stigmatized topic.

There is no simple answer for what causes or drives eating disorders, and understanding this is part of the key to prevention. Underlying triggers that have been known to cause eating disorders include past abuse or trauma, low self-esteem, bullying, poor parental relationships, borderline personality disorder, substance abuse, non-suicidal self-injury disorder (NSSI), a perfectionistic personality, difficulty communicating negative emotions, difficulty resolving conflict, and genetics. The provocations for our characters are endless and necessary.

Pulling our play’s storytelling focus away from explicit depictions placed an exciting challenge rather than a limitation for us: it challenged us to focus on the emotional drivers of eating disorders, allowing understanding and empathy to flourish. It also forced us to rely on structure and character to drive home catharsis, rather than spectacle or shock.

Making the Unsafe Safe

Far from pretending that eating disorders are not painful, scary, or challenging realities, a well-constructed piece of theatre for young people should provide the at-risk with a safe space to engage in the questions and challenges of this health epidemic. The pursuit of accuracy or authenticity should not further endanger them.

The theatre has always been an ideal place to explore the unsafe: with mirror neurons firing, our brains view the action ahead of us and vicariously process it, preparing us for the emotional challenges of our own lives. As theatremakers, it is our job to frame eating disorders compassionately, to create an environment that’s free from judgment and that’s instead full of empathy. We must signal in our practice and performance works that our bodies deserve to be cared for and kept safe.

If you are about to embark on the journey of eating disorder representation, especially in work that is directed at young people, here are several things to keep in mind:

- Clarify the desired impact of your work: Is it to educate, explore, enlighten, prevent?

- Identify a way to frame the disorder that keeps audience members safe.

- Avoid explicit depictions of disordered behavior (starving, binging, purging) to prevent contagion.

- Develop resources for audiences that encourage critical thought about the work and the topic.

- Protect actors by enforcing confidentiality. Reinforce the role of therapeutic resources if they are at risk (rehearsals are not a substitute for medical support).

- Consult with survivors to prioritize accuracy in your material.

- Consult educational organizations to ascertain the appropriateness of your material for young audiences.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I really appreciate your interest of issues such as eating disorders by working with teen actors. People sometimes don’t understand these issues because the not educated about this topic since it is very sensitive.

Thank you for your comment, Kitty!

In my experience, I prefer describing the more explicit elements associated with ED as 'behaviours', or maybe even 'misplaced coping strategies' rather than listing the actual practices. This was the language I developed around it in a therapeutic context and it feels a little more objective. It also re-directs us to think about the actions as symptoms of something else, rather than becoming the focus in isolation.

Perhaps the same "death by" phrasing and logic could be used in reporting, for example: "death by anorexia" (anorexia does have an incredibly high mortality rate)?

I greatly appreciate your discussion on trigger warnings as a tool to discuss potentially harmful subjects with compassion!

Have you found that there is language that better facilitates connecting with ED survivors? For example, journalists are urged to use "death by suicide" when discussing suicide in the media.