The History of the Cultural Vampire

Monsters are born from the projection of cultural fears onto the body of an ostracized “Other.” As these fears shift, so too do the characteristics of the monster. Throughout history, the male Jew has been demonized as Satanic, animalistic, and over-sexed, as well as effeminate, sickly, and impotent. In the Weimar Republic, the tropes merged: The Jew was at once a harbinger of disease—intentionally spreading syphilis to his many sexual partners and polluting German women with his inferior bloodline—and a weak, feminized queer, whose deviant sexual behavior and propensity for illness rendered him inferior to German men.

The vampire accompanied the queer Jew from the medieval period through the twentieth century, and in the 1920s he manifested as Count Orlok, who represented both sides of the same, queer coin. This Nosferatu was balding (a symbol of impotence; of circumcision displaced from the penis to the scalp) and effeminate (delighting at sucking a man’s finger). But he was also oversexed (feeding on men and women indiscriminately) and animalistic (rat-like in appearance, and accompanied by swarms of vermin). In short: he was everything Christians had feared about Jewish people for a thousand years, much of which stemmed from the alleged health effects of their supposedly deviant (aka, non-heteronormative) sexual behavior.

A few years later, Hitler blamed Jewish and queer people for spreading syphilis and “degeneration,” and equated Jews to plague-carrying rats in his propaganda films. During the AIDS crisis, the same rhetoric of health and morality was used to label AIDS a “queer disease.” The media likened queer people to monsters and serial killers on account of their alleged threat to public health, the sacred family unit, and the spiritual health of the nation. The discourse of invasion was also applied, such that AIDS came to be seen as a “foreign” disease “invading” American borders. Like European Jews several decades before, queer people were painted as a predatory foreign entity.

I believe Nosferatu, The Vampyr still serves to dismantle antisemitic tropes, due to the fact that Jewishness and queerness are inextricably bound in vampire lore.

Nosferatu, The Vampyr

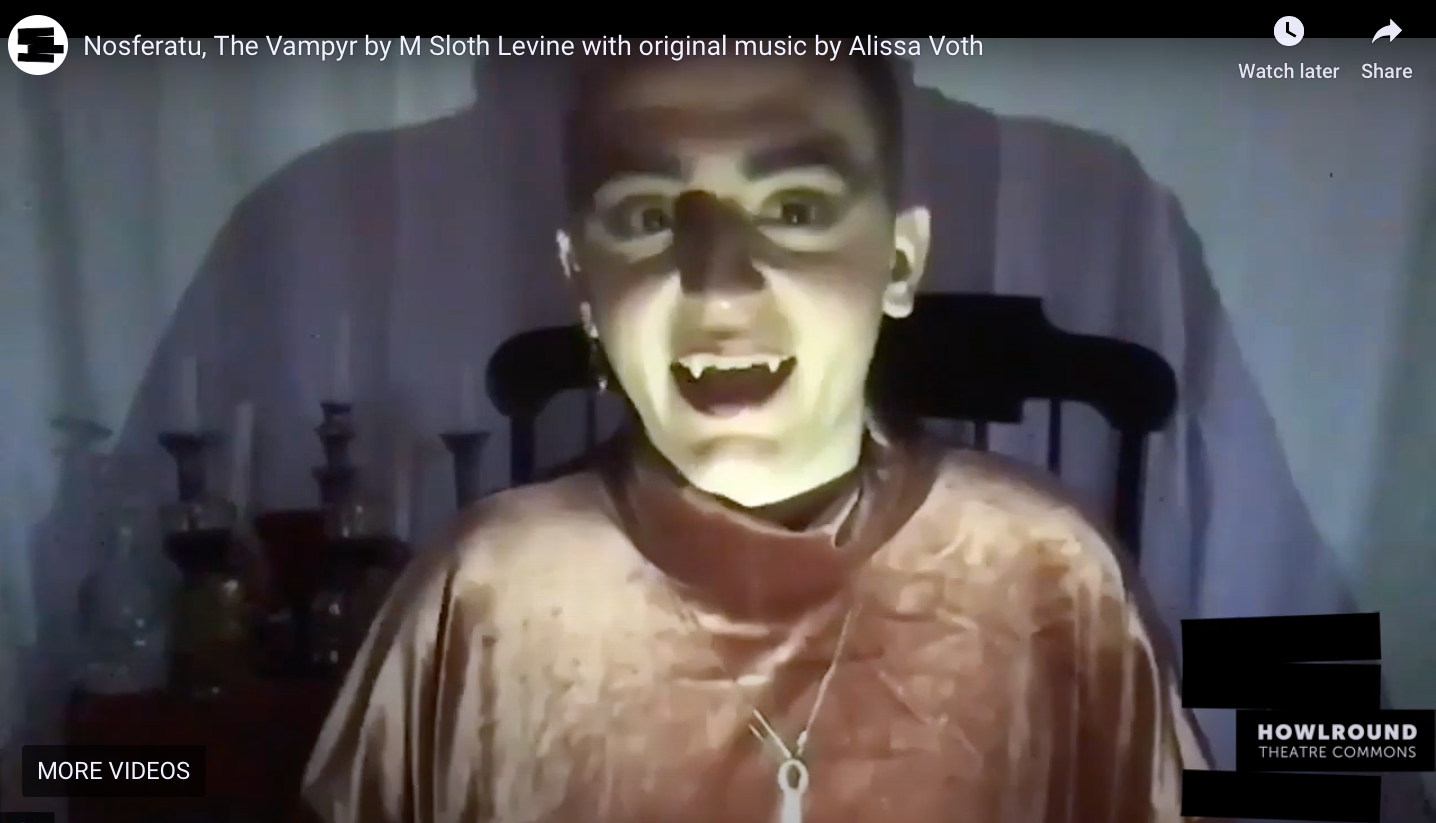

Stoker and Murnau’s tales were successful conduits of propaganda because the vampire’s queerness and Jewishness were veiled beneath heterosexual love stories. This subtext of hatred, fear, and repressed desire infiltrated the viewer’s mind, normalizing the image of the queer, Jewish monster, and intensifying pre-existing prejudices towards queer and Jewish people. By giving the Count in Nosferatu, The Vampyr an explicitly queer identity and pointedly sexual appetite, Levine prevents the semi-conscious absorption of queerphobic, antisemitic ideology and stereotypes. Stripped of ambiguity, the queer-Jew-vampire can be recognized as a social construction.

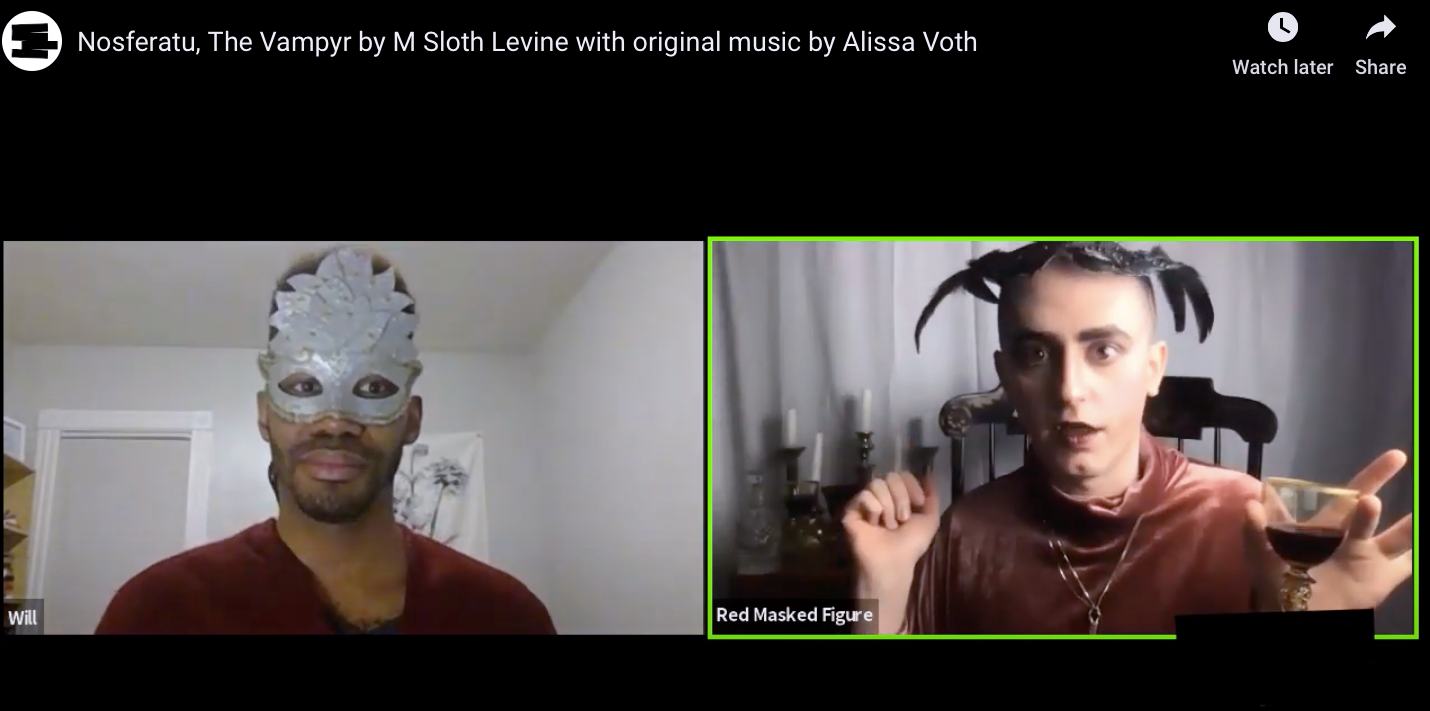

Subverting a powerful stereotype is a significant achievement as is, but what makes Nosferatu, The Vampyr truly profound is the way the story links its source material to queer trauma and contemporary queer experiences. From the bare bones of the deconstructed vampire tale, Levine constructs a complex queer narrative in which a plethora of queer voices are heard. Orlok is non-binary, and Harker (Dev Blair) and Will (Maurice D. Palmer) are a happily married trans couple. Lucy (Victoria Brancazio) is polyamorous, and her partners span the gender spectrum. Nosferatu, The Vampyr retains the structural components of its source material, but its characters experience the fears, joys, and mundanities of queer people today—a level of realism achieved, no doubt, by a creative team and cast composed almost entirely of queer and/or non-binary people.

These bare bones are a constant, quiet presence beneath the surface of the story; not the structural beats of the vampire tale, but the specter of a mythologized figure—the queer predator—who hovers in the background, in those liminal spaces where the light from my laptop cannot reach. Levine’s characters are not archetypes, but their lives are affected by queer history, and the queer-vampire-Jew is an unfortunate pathogen in that history. Its ghostly detritus manifests as trauma, enveloping the tale like an invisible plague and burrowing deep inside Orlok’s psyche.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Great article! Just also wanted to point out the spelling of Antisemitic. :)