Why is Jewish Theater Producing Asian American Plays?

#JewPlay: What is the future of Jewish theater in the United States? In this series, co-curators David Winitsky, Artistic Director of New York’s Jewish Plays Project and Guy Ben-Aharon, Producing Artistic Director of Boston’s Israeli Stage, asked Jewish theater practitioners from major regions of the country what Jewish theater means to them.

“Why is a Jewish theater producing a play about Asian Americans?”

This is a question we anticipated as we prepared to open David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face at Theater J—a professional theater and one of several cultural programs of the Washington DCJCC—in January of this year. The easy answer was “well, they do talk about Siberian Jews!” which is, in fact, a comical side plot in Hwang’s wild and funny ride of a play. But that wasn’t the real reason.

We chose to do Yellow Face because of the meaningful questions it raises about the parameters of identity. We chose to do Yellow Face because of the revealing and resonant glimpse it gives at immigrant families in the United States; because of its multi-layered examination of the “American Dream”; because of the uproarious and irreverent way it uses humor to expose darker themes. We chose to do Yellow Face because clearly, it’s a Jewish play!

But what does that even mean?

I’m pleased to report that the play was well received by both our long-standing patrons (subscribers and friends of the theater) and the sizable new audiences who came to our theater for the first time. Very few people asked why we were producing this play—they recognized the same qualities and values that attracted us to it.

In addition to an expanded audience, we found ourselves enriched by the community of Asian artists we were working with—several for the first time (including our brilliant director, Natsu Onada Power). They shared with us, in rehearsal and in post-show talkbacks, a sense that they’d found something of a parallel community here. We acknowledged a shared recognition of the story Yellow Face tells—of a community simultaneously united in its efforts to have its voice heard (figuratively and literally), but with differing ideas about how this should be achieved.

An Ever-Changing City

Theater J articulates its mission as: “producing thought-provoking, publicly engaged, personal, passionate and entertaining plays and musicals that celebrate the distinctive urban voice and social vision that are part of the Jewish cultural legacy.” In the past five years we’ve embraced that urban voice by recognizing with greater depth the community beyond our specifically Jewish community—that is, the community that comes with being a part of the vital and diverse city of Washington, DC.

According to the website areavibes, which compiles data from the US Census and other sources, the neighborhood in which we reside (Dupont Circle) is approximately 75 percent Caucasian, 8 percent African American, and 6 percent Asian (with other races making up the other 11 percent). Once affectionately referred to as the “fruit loop,” Dupont has also an active LGBT community. This marks a change from the period between the race riots of 1968 (which resulted in a dwindling population and boarded up storefronts) and the reversal of white flight in the 1980s and 1990s. During that time the historical building in which we reside was sold to the city and operated as Federal City College, a forerunner to the University of the District of Columbia.

When you expand the current demographics to the whole of the District of Columbia, the numbers reveal an even more diverse population. Now on a continual growth curve, the District added 30,000 residents between 2010 and the end of 2012 (that’s compared to the 20,000 it gained in the entire preceding decade, according to The Washington Post). A Census Bureau report found that as of July 2012, an estimated 50.05 percent of DC's residents were "black or African American" (Washington City Paper). The same Census report lists Caucasians at 42.9 percent, Hispanics at 9.9 percent, Asians at 3.8 percent, and other minorities at 3.3 percent. One of only five states (or equivalents) with a majority-minority population this landscape is also rapidly changing as neighborhood after neighborhood is taken over by trendy restaurants and high-end apartment buildings.

So when it comes to telling stories that reflect the make-up of the community in which we reside, it was becoming increasingly clear that stories about race and identity (and indeed—gentrification!) were an essential part of our narrative.

This isn’t a brand new idea. In the mid and late-1990s, the center engaged in a program titled Windows and Mirrors, a collaboration between the DCJCC and the African American Resource Center at Howard University, which celebrated shared traditions between the African American and Jewish communities. In many ways we are picking up where that programming left off.

Diverse Stories Illuminate Our Own

In 2008 we produced a play by a Slovenian-American playwright, which ended up winning the 2009 Charles MacArthur Award for Best New Play at the Helen Hayes Awards. What was Jewish about Stefanie Zadravec’s Honey Brown Eyes? Nothing overt. This play, which introduces us to two young men on opposite sides of the Bosnian war, was our first exploration of parallel narratives. In 2010 we produced Winter Miller’s In Darfur, a richly-researched work about a young Darfuri woman caught in the ongoing genocide in the Sudan and the American female journalist intent on telling her story, in the hopes that it might affect some change.

In 2012, we told the story of two young men—one a former slave and the other a Jewish former slave-owner—caught in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War with Mathew Lopez’s play The Whipping Man. In 2013 we programmed David Mamet’s Race—in many ways an obvious choice (a play by a popular Jewish writer) but in other ways a play that stretched us into new territory. None of the characters are specifically Jewish, and the essential questions of the play revolve around perceptions of race.

We continued that season with a deeply personal play by our Artistic Director Ari Roth, Andy and the Shadows, which includes amongst its examinations a look at race relations in the South Side of Chicago. And we finished the season with the first play Theater J has produced by an African-American playwright, Jacqueline E. Lawton’s The Hampton Years, which told the story of a Jewish refugee from Austria coming to the United States with his wife and son, and then rejecting the anti-Semitism of the Ivy Leagues by choosing to teach at an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) instead.

The Sum of Our Parts

One of the most satisfying outcomes of our expanding mission is the way in which our “obviously Theater J” plays engage in a meaningful dialogue with our “less-obviously Theater J” plays. This season that’s played out with Hwang’s Yellow Face and Amy Herzog’s After the Revolution. Herzog’s play tells the story of a politically radical Jewish family veering into the start of the twenty-first century. When new revelations about the deceased family patriarch come with the release of the Venona project documents, the family is thrown into turmoil. Words like “loyalty” and “spy” are bandied about and the Rosenbergs are evoked. These same words all come up in Yellow Face, as do Ethel and Julius.

This happened again with the world premiere of Darrah Cloud’s Our Suburb and the newly-commissioned version of Alexandra Gersten-Vassilaros’ The Argument. Our Suburb, like After the Revolution, looks at a major event in Jewish-American history: the proposed (though never completed) Nazi march on Skokie, Ill. It also tracked the rise of feminism and the growing number of options for women in the late 1970s (set four years after the passage of Roe v. Wade) in a very human and intimate way. The Argument (again, a play with no specifically Jewish characters) picks-up twenty five years later with an incredibly personal look at the politics of choice (both reproductive choice and the choices surrounding life and career). The two plays together acknowledge and scrutinize the accomplishments of the women’s movement, and the ways in which it may have failed us as well.

So why is a Jewish Theater producing plays about Asian-Americans, abortion, an Okie folk singer (Woody Sez) and a historically black college? Have we become one more theater embracing a “multi-culti” mission while still purporting to be culturally specific? I don’t think the two are mutually exclusive. The stories we tell that come from other cultures resonate with both our Jewish community and the larger DC community—of which we aim to be a vital and important member. We are serving our community by expanding our community. This has kept us engaged and relevant.

***

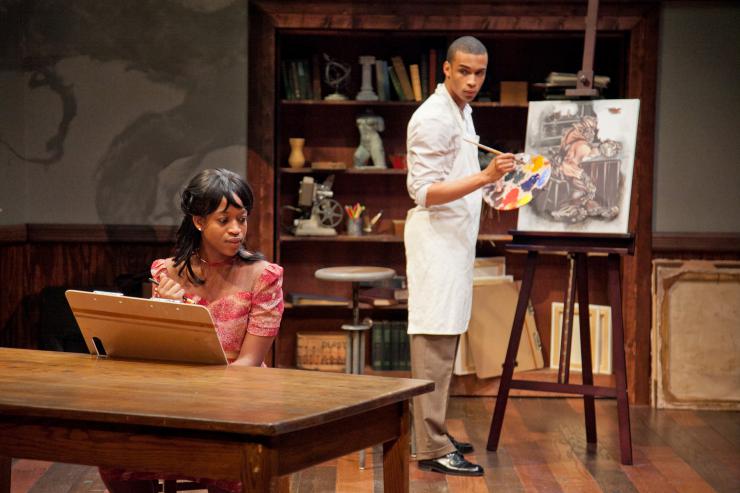

Images: Scenes from Yellow Face and The Hampton Years. Photos by C. Stanley Photography.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Wonderful essay!

Beautifully written piece. When the whole DC theater -plays-in-the-pipeline thing was blowing up online, I had wanted to stand up and point to Theater J. How in an effort to deepen their mission statement Theater J, (a theater with a supposedly narrow focus) always manages to find and produce smart plays by women writers and writers of color. Not as a forced and self-conscious act, but simply because of the kinds of smart and compelling stories they are interested in telling. In my case, (2008's Honey Brown Eyes) they chose an untested play by a then unknown playwright, because they thought it was an important story told in a compelling manor. As Shirley states, it extended the conversation for Theater J's audience. As a writer, the ongoing community conversations, allowed me to experience the impact of my work in a way I never had. Beyond reviews and awards, it was a completely meaningful and rewarding experience.