Let Us Not Thumb Our Noses

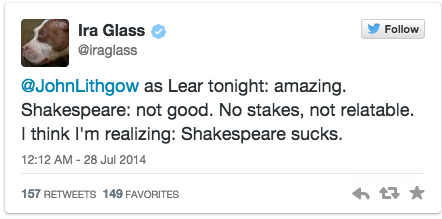

Recently, Ira Glass insulted Shakespeare. The Internet picked up its pitchforks.

He said:

I was delighted.

The New Yorker, on the other hand, skewered him in an article by Rebecca Mead that examined the provenance of the word relatable, asking us to thumb our noses at lazy, solipsistic, selfie-taking Millenials. In my own Facebook feed, full of Shakespearean actors and lovers like myself, it was the popular choice as the best available retort to Ira’s insult. The article closed with the following remarks:

to reject any work because we feel that it does not reflect us in a shape that we can easily recognize—because it does not exempt us from the active exercise of imagination or the effortful summoning of empathy—is our own failure. It’s a failure that has been dispiritingly sanctioned by the rise of “relatable.” In creating a new word and embracing its self-involved implications, we have circumscribed our own critical capacities. That’s what sucks, not Shakespeare.

I did not see John Lithgow as King Lear, and I do not pretend to speak for Ira Glass. I also do not want to thumb my nose at Rebecca Mead. But this was unfair to Ira, ungenerous to my generation, and uninspiring as a guide to meaningfully relating to Shakespeare’s plays.

We can bridge that distance and improve our Shakespeare by closing the social loop between crowd and stage that Shakespeare never intended to break, and by taking advantage of a very contemporary, even Millennial, desire to relate to what we watch.

I have dedicated my entire adult life to the study and performance of Shakespeare, and I for one think Ira Glass had a point. Most of the Shakespeare I see is not good, has no stakes, and is difficult to relate to.

I would like to address more deeply and more practically the question of how we are to relate to Shakespeare’s plays in performance. Because for those of us who make a life from Shakespeare’s plays, the theatrical expression of those plays must be the primary expression. Whether and how an audience relates to them is sacred. That is the faith we keep.

Shakespeare did not write for us; he wrote for the Elizabethan theatre. And how an Elizabethan audience related to theatre is fundamentally at odds with how we are supposed to relate to theatre today. We pay a heavy price for ignoring the distance between Shakespeare’s theatre and our own. It causes us to make his plays sanctimonious, formal, and yes: unrelatable.

We can bridge that distance and improve our Shakespeare by closing the social loop between crowd and stage that Shakespeare never intended to break, and by taking advantage of a very contemporary, even Millennial, desire to relate to what we watch.

*

For the last three and a half years in Chicago, I and many others have worked to keep that faith, and to bridge that distance. That work is called the Back Room Shakespeare Project.

I don’t speak for all of us who work on the Project. I speak for myself. But from my point of view, the basic idea is this:

The audience Shakespeare wrote for was a bloodthirsty bunch of drunks who came for the bear-baiting and stuck around for the tragedy. They were practically on stage, buying nuts and beer from wandering vendors all the way to the bloody end. There was no director. The actors owned the plays. They costumed themselves. They inserted their own bits when they felt like it. They rehearsed the fights, said their prayers, and tried to tell the truth.

Hell of a legend.

The work of the Back Room Shakespeare Project is to use that legend to pry Shakespeare out of the cancerous, rotten jaws of modern convention.

We are not trying to re-create Elizabethan London. We are trying to create an environment where Shakespeare’s plays can really come alive, where people can really relate to them.

For the Project, as in Shakespeare’s day, there are no directors. We cast and costume ourselves, collaborating independently with one another as we choose. In general, we perform only once. The audience is our complicit partner, not a passive observer. When we’re at our best, it all feels like a conspiratorial slumber party wrapped tightly around a play—whatever might happen, it’s happening to all of us.

*

Say you went to the Cockpit, or the Curtain, or any of the bankside citizen playhouses along the Thames in the late 1590s. The theatre was permeable, responsive, and fluid. It was essentially social in scale. You could get a beer during any act. You walked around, crunched nuts, you clapped and booed as the players pleased or displeased you. You did some business with your cousin, and you checked out or avoided the prostitutes, as your tastes dictated. You jockeyed for good seats—not just where you had a good view of the play, but where the crowd had a good view of you. A guy might stab someone in a tiff over a seat. Some of the stages even had fences to keep the crowd back, because every now and then some yahoo felt moved to climb on stage and participate.

We know all this because the playwrights complained about it all the time, publicly and privately—in poems, letters, and the forewords to their published works. They thumbed their noses at the lazy, solipsistic gallants more interested in showing off their outfits than in listening to the play.

But they didn’t just complain; they got to work—turning that dicey, charged environment to their advantage.

The plays-within-plays in Shakespeare (and more broadly, of the period) are a good example of this. In them, audiences discuss, undercut, applaud, and otherwise interact with the play they are watching. Although magnified (as all things in theatre are) to the point of clarity, the relationships are plain as day. And yes, it’s easy to see in this the hand of the playwright poking the audience in the eye, showing them why they should shut up for once, but it’s also a good filter with which to draw out what those playwrights were doing across their work: roping in those preening, self-obsessed nobles, scooping up the seething, social pit of groundlings, and enlisting them as rich theatrical resources.

Think a moment: the bare fact of the soliloquy ought to give us serious pause. The characters talk directly to the audience. That’s weird. Nowadays, we sort of live uncomfortably with the soliloquy as a tradition. Like a sad uncle who’s had too much to drink, we humor it, but we don’t trust it in mixed company.

Our suspicion is hard to reconcile with the theatre Shakespeare wrote for.

Because for the Elizabethans, the soliloquy was not an outlier, and did not temporarily change the rules when it showed up. It defined and typified the crucial hallmark of their theatre: an active, complicit relationship with the audience.

I have seen and loved a lot of Shakespeare at a lot of truly great theatres in this country. But in what I have seen, that specific kind of complicity has been almost entirely absent.

Shakespeare’s audience went to the theatre as an essentially public, social act. Today, we mostly go to the theatre as a private, observational act.

And how could it be otherwise?

Every convention of your average modern theatre serves to distance the audience from the play and from one another, make them passive, docile, almost entirely erased. We’ve taught American audiences to shuffle amiably and wash their hands. We tell them where to sit. We give them a potty break. We tell them to shut up and turn off anything at all that might make any kind of noise. We provide them no reason to ever have to interact with the person seated next to them. The pacification is profound: we don’t even trust them to unwrap a sucker in the theatre. We imply in a thousand ways that everything has been worked out in advance, encouraging total passivity of body, mind, and spirit. And then we turn the lights out on them and expect them to listen to complex, antiquated verse poetry that relies on an active, participatory relationship.

Can we really blame them for finding it a bit hard to relate?

When we try to jam Shakespeare’s plays into our modern theatres, when we make them follow modern rules, we alter them violently.

The difference between talking to an audience and being in a real relationship with an audience is very simple. Information must flow in both directions.

We live in the shadow of Realism, whose central tent-pole is the Suspension of Disbelief—a phrase coined in 1817: two hundred years after Shakespeare died. (For reference, that’s Jay-Z versus Ralph Waldo Emerson.)

The Suspension of Disbelief was not a part of Shakespeare’s theatrical tradition. On the contrary, he and other playwrights of his time kept their audiences tightly leashed to their actual surroundings by constantly enlisting them as complicit players in meta-theatrical games, with characters saying things like if this were played on a stage now, it would never be believed. He made constant use of the actual context and environment of the theatre.

For this reason, I think of it not as Realist, but as Actualist theatre.

But we who live in the shadow of Realism extrapolate, wrongly, that the Prologue to Henry V is asking us to suspend our disbelief. We imagine the fields and the horses, and we overlook the lines that strap us to the actual theatre we are sitting in, the lines that remind us forcefully of the role we are to play as participants.

This kind of actualist metatheatricality pervades Shakespeare’s writing. It is at the heart of one of Shakespeare’s darkest and most haunting speeches:

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.

Hamlet has a 59 verse-line soliloquy that weaves a complex net of reality and unreality that binds the audience both to actual and fictional truth.

Now I am alone.

O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!

Is it not monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his own conceit

That from her working all his visage wann’d,

Tears in his eyes, distraction in’s aspect,

A broken voice, and his whole function suiting

With forms to his conceit? and all for nothing!

Let me be clear: we’re talking about something other than direct address.

The difference between talking to an audience and being in a real relationship with an audience is very simple. Information must flow in both directions. When the actors deliver lines to the audience, that’s not a relationship. When the audience visibly or audibly responds, and the play includes that response as a part of what is happening, that is a real relationship.

Think of the comment box placed at the bottom of this article. It invites a relationship. Furthermore, it is even stipulated in my contract with HowlRound that I must participate in that comments section. That’s a real relationship. I look forward to the conversation it creates.

Theatres could stipulate the same agreement with their actors: that they must participate in what could be called the comments section of the performance—in a more meaningful way than by pausing for laughs.

Take Richard and Anne’s fight over the corpse of Anne’s dead father-in-law in Richard III. It is often played as the private seduction of an emotionally unstable woman. This gives Anne little to do but fall victim to the awful advance of evil before she exits and the scene breaks out into a delightful soliloquy, the villain explaining himself to a docile audience.

But if you play it with complicity—if you allow the audience to actively relate to the unthinkable seduction on stage—you will see that it is not so very far off from a Twitter flamewar. In both cases, the fact that an audience is watching is essential as to why the fight is happening at all, and also how it happens. In both cases, you must keep the tension of the argument in one hand, and the tension of public perception in the other. And in both cases, the audience will be immeasurably more in the grip of the unfolding drama because they have a voice, however small or implicit, in its process.

And this is why I refuse the accusation at the heart of that New Yorker article: that my lazy, solipsistic generation is incapable of relating to Shakespeare.

*

Our social lives are becoming increasingly performative and public. One hardly dare so much as eat a meal anymore without Instagramming it, tagging it, and favoriting selected comments to follow. This gives us more in common with Shakespeare’s crowds—and characters—than we imagine.

Let us not thumb our noses, then, at the self-aware hipster who is conscious not just of what she does, but of how she does it, who is perceiving it, and how they are reacting. Let’s put her on stage, and let’s buy her a beer she can drink at the theatre. Because that is exactly what Shakespeare calls for.

Let us create an environment of our own that will create the kind of relationship between the actor and the play, between the actor and the audience, between the audience and the play that will help people to relate meaningfully to Shakespeare’s plays.

Because those plays thrive on an intimacy that is both arrestingly direct and achingly self aware. Shakespeare needs his players to seize hold of the bloody spine of his verse, and hold it writhing while they look the audience in the eye. And he needs his audience to meet that gaze, reach out, and grasp the writhing spine the players offer. That is the faith we must keep.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The writing in this article was one portion of a larger whole. Since then, that larger whole has become a little book. At present (3/6/2015), it is about to be printed.

More information is available here: https://www.indiegogo.com/p...

Love Love LOVE the ideas and vision expressed here. I have been feeling around for this performance aesthetic for a while, and got the chance to articulate some of it in my senior thesis (not nearly as well as you did here, Samuel):

"When I began this project, my hope was that the consequences of this study would identify various elements that combine to create the “theatrical experience.” What I am left with is not a recipe for the perfect production; obviously, that does not exist. What I have gained is a new sense of possibility, both in terms of my own capacity to blindly stumble into theatre that is useful and compelling, and in terms of how theatre can transcend “skeptical impediments” and the “egocentric predicament.” This research and this experience have helped me escape my cynicism through the discovery of something that feels new. “[Susan Bennett] calls for the ‘emancipation of the spectator’ evident in non-traditional and often marginalized theatre practices, which allow for a more active role for the audience” (Fortier 137). The concept of “willing suspension of disbelief” is widely accepted, but maybe it’s time for a different paradigm- a willing acknowledgement of what is strongly believed, perhaps."

My even-more-cynical post-grad artist self needs to keep reading articles (usually on Howlround) that remind me of this discovery. As you said in a comment below, it's helpful, and necessary, to "connect the dots working in isolation out there."

Thanks for throwing out a connection, and thanks for spreading the word about BRSP. I hope that my travels to Chicago coincides with one of your projects!

I hope your travels coincide with one of our shows here, too. I think the emancipation of the spectator is a good phrase, and a good battle cry.

Great article Sam! I'd love to see one of your shows in Chicago. I think one of the reasons theatre has survived the technology revolution is its ability to create intimate interactions between audience members going to the theatre and between the performers and the audience. I think audiences often find a lack of connection among one another and with performers in "classic" plays. They often are reproduced soley because they are recognizable. I think it is on track to be skeptical of an abscence of intimate connection in these performances.

Finally, an article about the modern performance of Shakespeare I can get behind! I also grew up studying, loving, and being inspired by Shakespeare, but became disillusioned with it the more I saw it. I've been trying to articulate why I think it's become so stale for me, and I think you raise an incredibly relevant point that doesn't negate my experiences as a Millennial. Ultimately I feel that nowadays a lot of Shakespeare productions are just being put on for their marketing potential and the artistic goal follows after. I think the plays are seen as convenient vehicles for discussing topical issues because the plays themselves contain such universal truths (and are familiar and therefore more safe), but instead of watching a production of Macbeth set in Uganda - for example - I would really rather just see a new play about Uganda. I think Shakespeare's plays are brilliant and deserve productions today, but only in a very purposeful way. As you said, Shakespeare didn't write for our time, and while I have seen a few very successful modern adaptations of Shakespeare, I've enjoyed the most the ones that just got out of the way of the text and didn't try to turn it into anything it wasn't. We should focus less on making it relatable or familiar, and think of how it can truly engage an audience and why we need that particular play to do that. I look forward to checking out the Back Room Shakespeare Project the next time I'm in Chicago!

I think you're dead on. Shakespeare's plays have become a sort of blank template on which theatres paint their own stories: Romeo and Juliet is about moneyed privilege, Hamlet is about disfunction and misogyny, Julius Caesar is about masculine pride in American politics... and so on.

When we started working this way, it brought the actual plays to the surface with such alarming clarity. People routinely say that we are some of the clearest shakespeare they've seen, and i think that's the reason. Not because we are wizards of some kind, but because the thing that is happening is the play that was written, in the style in which it was written.

It's so great to read about this. I'm such a fan of Back Room Shakespeare. My one time attending was one of the most exciting nights I've had in the theater, and I so look forward to seeing it again soon!

Thanks, Joanie.

I want to come to Illinois to check you guys out! If you're ever in Utah (or Alabama or London), you should check out The Grassroots Shakespeare Company. We're an original practice theater company, and it sounds like we have a ton in common--we're all about ripping down the fourth wall, bringing the audience in as active, complicit participants in the drama, creating collaboratively without directors or designers, and so on. It's amazing what performing Shakespeare the way it was written to be performed does to it. I hope our paths cross and we can talk about our respective projects sometime.

Sounds great, Davey. I hope we do cross paths. One of the reasons I wanted to have this article on Howlround was to start to connect the dots working in isolation out there. I think we make more of a shape than we know, if you connect us.

SO very well said. Bravo.

I am fascinated by the play of language around words like accessible, relatable, realism, and distance. The original goal of realism was to _decrease_ distance, to make things seem _more_ relatable, by getting the audience absorbed in the play. That was the same reason that we started turning lights off, and telling people not to make noise - so nothing would get between the audience and the story. Brecht advocated direct address (amongst other techniques) in order to _create_ distance, by reminding people they were in a theater. But he was not shooting for alienation - at least not the sort that Mara is referring to. (I know we associate that word with him, but I think that is a terrible translation). I would say that Brecht was trying to use distance to create the sort of engagement that mirrors what Samuel is talking about here - to get the audience involved, rather than being passive spectators who can feel free NOT to relate to the story.

That is fantastic, Annie. It's always a pleasure to work with the Lenox people of Shakespeare & Co. I may be wrong about this, but I think that one of our repeat actors -Sarah Taylor (No relation) helped run that program for years.

In case anyone has any doubts about Shakespeare being relatable to young people, I present you this: https://www.youtube.com/wat...

The Fall Festival of Shakespeare in Lenox, MA. Over 500 high schoolers bellowing text like it's the air they breathe. They laugh, they hiss, they shout back at their comrades. It's a sight to behold.

Too weird, I'm in this video! I agree though. The Fall Festival of Shakespeare was the absolute greatest experience of my life. I am now a sophomore in college, and am taking a Shakespeare course right now, and all of the plays we are studying, I know from Fall Festival.

Shakespeare is absolutely relatable.

The stories can be told hundreds of ways. It is fair to say that my generation does not appteciate Shakespeare's work nearly as much as I wish they did, but some of us do. It's unfair to lump all of us together. As Annie said, there are over 500 students involved in the Fall Festival of Shakespeare, and that is just in 10 high schools throughout Massachusetts and New York alone. Imagine if this opportunity was everywhere. It'd reach a much larger audience of people my age and younger.

Hi Mara.

Thanks for reading. I hope that this article is useful to you in your aspirations. Accessible is another one of those words with bad associations, in that it's often a nice way of saying that something is dumbed down, flattened out, and without any edge. I always hope to give the audience access to the edges.

This is what I love about BRSP, even though I never could have put it into words. Thanks, Samuel. Looking forward to the next installment of BRSP, and of your work here.

Great insights and your thoughts on the "relatability" or accessibility of Shakespeare productions extend to the theater in general. It is sad to see, as an aspiring actor and artist of the millennial generation, that the views towards watching a show tend to focus on that distance between actors and audience that alienate so many. I am also someone who wants to work with classical theatre pieces and works, and I want my future work to jump that distance and focus on sharing the truth at the heart of every play or musical. Thank you for your article!

What's also impressive is the writing in both this article and the New Yorker one.

Thanks, Jonas. And I'm glad it makes your brain move, Wyatt. It is doable.

Preach Brother!

Nicely put. Makes my brain move. Makes my actor's body ache with want. It's a doable thing. Inspiration and catalyst.