Andrew Jackson Is Not As Bad As You Think—He’s Far, Far Bloodier

This week on HowlRound, we are exploring Native voices on the American stage. I have deemed this week: “Instead of Redface” (#InsteadOfRedface)—as our voices collectively question why redface is more prevalent on the American stage than our own authentic Native voices. I asked Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee) to contribute her thoughts because as a recent recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama this past November, she is uniquely positioned to explain the devastating effects of the continued performance of redface on our Native Peoples, Nations, and communities. —Mary Kathryn Nagle

Many scholars know that Andrew Jackson, seventh US president, was an Indian killer and zealous champion of Alabama, Georgia, and other “states’ rights” to ethnically cleanse “state lands” of Native Peoples. Some acknowledge it, but sort of gloss over the Indian part. Some deny it and twist and obscure the facts. Some just copy what others copied before them and call it history or art.

When I criticize the emo rock musical Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, I don’t blame its creators for their initial ignorance, but for their resistance to knowledge, as well as for their failure to work with Native theatre folks and to recognize that Native professionals could have helped them.

Bloody Bloody opened at the Public Theater in New York City and moved to Broadway, where it suffered a mercifully short run in 2010. The Public held a meeting with some Native actors, directors, and writers, but only after the play was set and Broadway bound. It seemed they were looking for Native endorsements and never acknowledged that some of the arts veterans in the room could have made it better theatre. Instead, Native theatre pros’ comments were taken as criticizing “creative license,” which was particularly insulting for those who are free speech and artistic freedom warriors.

“How does history get all sexypants?” That’s how Broadway.com started its pre-opening tidbit in Broadway Buzz (Sept. 21, 2010):

The cast of characters may read like a dog-eared American history textbook, but the story is anything but stale. Andrew Jackson doubled the size of the United States, created the Democratic Party and—if Bloody Bloody is to be believed—kicked ass, broke hearts and rocked out…Join in as we hook up with (the company) and get an inside look at bringing to life one of American history’s biggest badasses.

For some Democrats, Andrew Jackson is the beloved founder of the Democratic Party. However, many citizens of Native nations who were wrenched from their homelands and forcibly moved to Indian Territory (now Kansas and Oklahoma) say they are Republicans today because Andrew Jackson was a Democrat.

My critique of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson is more than a matter of Western morality concerning right and wrong. For Native Peoples today, it’s about life and death. The dehumanizing, objectifying portrayal of Native People in Bloody Bloody, as well as in other contemporary performances of redface, perpetuate the nineteenth century American story that Native People are less than human.

Some Native Peoples wanted to move to Indian Territory to get away from the gold rushers, only to find themselves losing nearly all the new lands to land rushers, to oil gushers, to taxes, and to inheritors of the Jackson legacy who married Native women for their land and black gold, then reported finding the wives dead at the bottom of basement stairs.

They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement which are essential to any favorable change in their condition. Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear. —Pres. Andrew Jackson’s Annual Message to Congress, 1833 (excerpt)

Many people who think they know American history do not know this history, which means they do not know American history. Most who think they know about Jackson and Indian removal believe there was only one Trail of Tears and only the Cherokee Nation was removed. Or they know of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, and other Muscogean-speaking Peoples from the South and their Trails of Tears. Most Americans do not know about the Potawatomi Peoples’ Trail of Death from their homelands in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin to Indian Territory.

Jackson attempted as an Indian fighter to break up the Muscogee (Creek) confederacy of more than sixty Nations and Tribal Towns, and failed to do so. He won election to the US Senate, where he chaired the Indian Affairs Committee, whose membership and that of its House counterpart included his own former aide de camp and other Indian fighters. Together, they devised the Indian Removal Act. When Jackson became US President, he proposed an Indian Removal Act to Congress and they sent it to him in record time. Rep. Davy Crockett and others spoke against passage of the Indian Removal measure, but Jackson’s forces had the votes.

The Indian Removal Act required a removal treaty with an Indian Nation before its citizens could be moved. Some Native leaders thought that it was certain death to remain among so many non-Natives who hated them, so they signed or made their mark. In some cases there was outright coercion. Often, Native People did not know that their leaders had agreed to give up their homes until armed movers showed up.

If Jackson could not get a removal treaty, he gave removal orders anyway, as he did with the Muscogee (Creek) Nations. There was no removal treaty and removal was carried out at bayonet point. Not only that, but Muscogee lands taken through the Treaty of Fort Jackson, negotiated by guess who, were supposed to have been returned to the Muscogee (Creek) Nations, in accordance with the treaty that ended the War of 1812, but they were not. Tens of millions of acres were taken illegally, and the Muscogee Peoples still grieve over the displacement, ill treatment, and injustice, and for the homelands and ancestors left behind.

And is it supposed that the wandering savage has a stronger attachment to his home than the settled, civilized Christian? Is it more afflicting to him to leave the graves of his fathers than it is to our brothers and children? Rightly considered, the policy of the General Government toward the red man is not only liberal, but generous. He is unwilling to submit to the laws of the States and mingle with their population. To save him from this alternative, or perhaps utter annihilation, the General Government kindly offers him a new home, and proposes to pay the whole expense of his removal and settlement. —Pres. Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress “On Indian Removal,”1830 (excerpt)

With a president saying such negative things as if they were observable fact, it’s no wonder that name-calling, belittling, and objectifying Native Peoples became fair game in America. These attitudes are readily apparent today in the disparaging “Indian” stereotypes in sports, the demeaning images of “Indian” women in popular culture, trick-or-treaters “dressing up like Indians,” and wooden-Indian and Indian-maiden depictions on stage and in film and cartoons. Who could forget “What Made the Red Man Red?” from the Disney classic Peter Pan:

When did he first say, “ugh?”

When did he first say, “ugh?”

In the Injun book it say when the first brave married squaw,

He gave out with a big “ugh” when he saw his mother-in-law.

Ugh is right!

And we’re back to ugh’s direct descendant, Bloody Bloody. Here’s a song sample:

Ten little Indians

Standing in a line

One got executed

Then there were nine

Nine little Indians

Haven’t long to wait

One got syphilis

And then there were eight

…

One little Indian

Nothing to be done

He went and hanged himself

And then there were none

When I saw the show at the Public, there were even more cringe-worthy lyrics and dialogue. Yes, it was insulting, but in an abstracted way. Simply put, it was evident that the creative team had not employed, talked with, or listened to any Native theatre people. One person they could have tapped, but didn’t, was Muriel Miguel (Kuna and Rappahannock) of Spiderwoman Theater.

Muriel is theatre history—in the original company of Joe Chaikin’s Open Theater and as founder/artistic director of Spiderwoman Theater—and, although vigorous and agile, is an elder.

The smartest thing that the New York Native arts community did was to ignore the Broadway opening of Bloody Bloody, rather than call attention to it by protesting and run the risk of prolonging the run. Since then, Native and non-Native theatre people at Stanford University and in Minneapolis have blocked productions of the show. On January 12, 2015, the Raleigh Little Theater announced cancelation of its production. Its many production fits and starts indicate that the creative team of Bloody Bloody still may not hear what Native People are saying.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Muriel and I were two of barely a handful (and I do mean a handful) of Native People in theatre in New York. I co-produced Native programs and was Drama and Literature Director for WBAI-FM radio station, where I got to produce such great projects as three original plays for radio that Samuel Beckett wrote for Joe Chaikin’s direction. And Muriel and I were always on tap for Joe Papp’s readings and fundraisers at the Public.

Muriel asked her girlhood friend Josie Tarrant (Winnebago and Hopi) and me to join her in a Native women’s improvisational group she envisioned, and we became the first Spiderwomen. Alas, Josie caught the flu and died, and I moved to Washington, DC. Muriel says it broke her heart, but she regrouped magnificently and worked with her sisters and now with their children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren to form the Spiderwoman Theater of today. Despite Muriel’s talent, experience, and longevity in the field and with the Public, she was overlooked when it came to script doctoring, improv staging, or any kind of help with Bloody Bloody, although the Public subsequently presented Muriel, me, and Soni Moreno of Pura Fé (an original version of the Native singing group Ulali) in a discussion of our experiences in New York theatre in the 1960s.

My critique of Bloody Bloody is more than a matter of Western morality concerning right and wrong. For Native Peoples today, it’s about life and death. The dehumanizing, objectifying portrayal of Native People in Bloody Bloody, as well as in other contemporary performances of redface, perpetuate the nineteenth century American story that Native People are less than human. The lessons of Bloody Bloody are seen in American society today. Today, Native women are murdered at a rate higher than any other race in America. The majority of the perpetrators of violent crimes against Native women are non-Native men. The “jokes” in Bloody Bloody about killing Indians are not “jokes.” They are a reality.

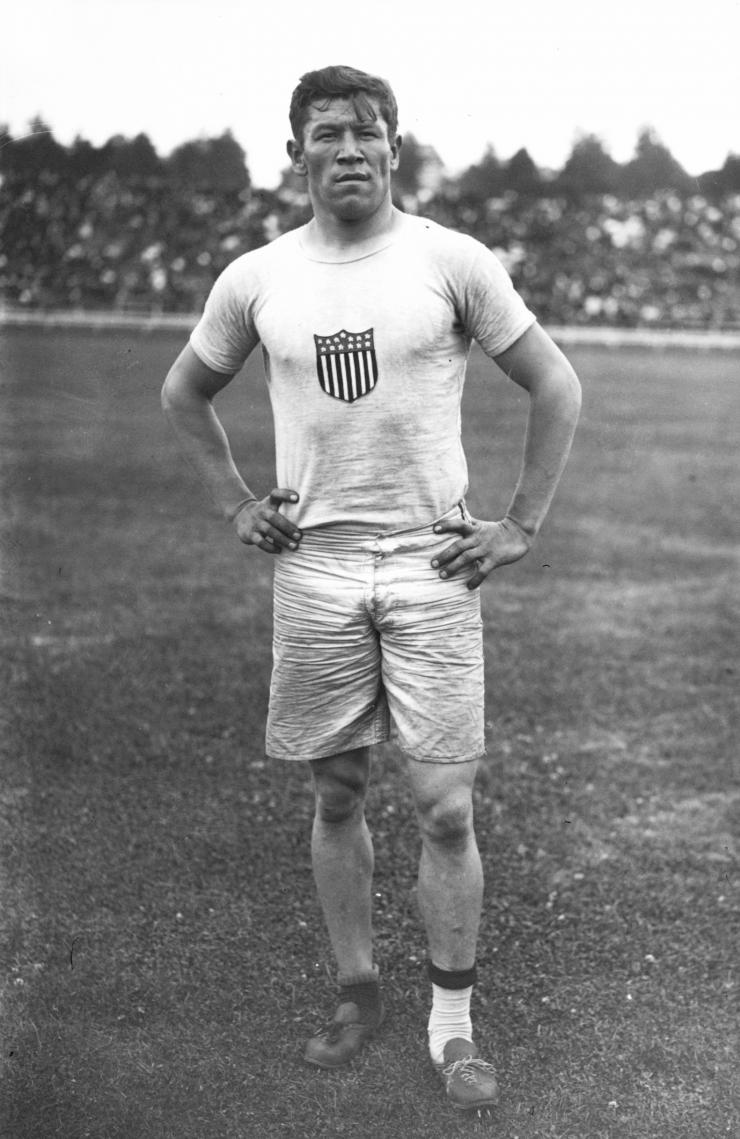

Or, take the story of Jim Thorpe. Jim Thorpe was Thunder Clan and a citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation, and a world-class athlete and Olympic gold medalist. He passed away in 1953 and the Sac and Fox Nation was carrying out his traditional burial, in accordance with his last wishes. Ordinarily, this Sac and Fox funerary process involves four days of ceremonies, followed by burial in Sac and Fox territory, where Jim Thorpe wanted to rest. However, on the fourth day, his third wife, Patsy, who was not Native, interrupted the returning-the-name ceremony, which is the last step before burial in Sac and Fox land. She burst into the quietude of this ceremony and took his body. The mourners were so stunned at this unprecedented disruption that they could do nothing to stop the desecration.

Jim Thorpe’s widow then shopped his remains to several cities, looking for the highest bidder. She found what she was looking for in Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, a town that agreed to pay her for Jim Thorpe’s body and rename the town “Borough of Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania,” in the hopes that it would see an increase in revenue from tourists looking to see the burial place of the man known as the greatest athlete of the twentieth century. For years, his sons have sought the return of their father to his home, so that they can complete his burial ceremony and put him to rest in the cemetery next to his siblings, parents, and now, children.

In October 2014, the Philadelphia-based Third United States Circuit Court of Appeals said that Thorpe's body should remain in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, determining that the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, which requires museums and other holding repositories possessing Native remains to return them upon request of the deceased's family or tribe, had been misapplied. Jim Thorpe’s sons’ efforts to bring their father home have been thwarted by an American legal regime that privileges white ownership over respect for Native religion, culture, and family. Undoubtedly, the defilement of Native identity in shows like Bloody Bloody signal that it’s okay to steal Native land and even bodies, disrupt Native burial ceremonies, ignore the last wishes of Native People, and make roadside attractions of Native persons, because Native People are only valued in death and as the property of non-Native America. Native Peoples worked for more than twenty years for laws to make certain that Native human rights would be recognized and that the kind of thing that has turned Jim Thorpe into a tourist trap would not happen again.

On February 12, I worked with the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology to stage a reading of a play I co-wrote with Mary Kathryn Nagle, entitled, My Father’s Bones. Our play follows the journey of former Principal Chief Jack Thorpe, Jim Thorpe’s son, as he struggles to bring his father home. If American theatres were to produce plays that substitute authentic Native stories for redface, Native People wouldn’t have to fight for years to repatriate the remains of their loved ones that have been “purchased” by non-Natives. The play was livestreamed on HowlRound TV, and you can watch it here.

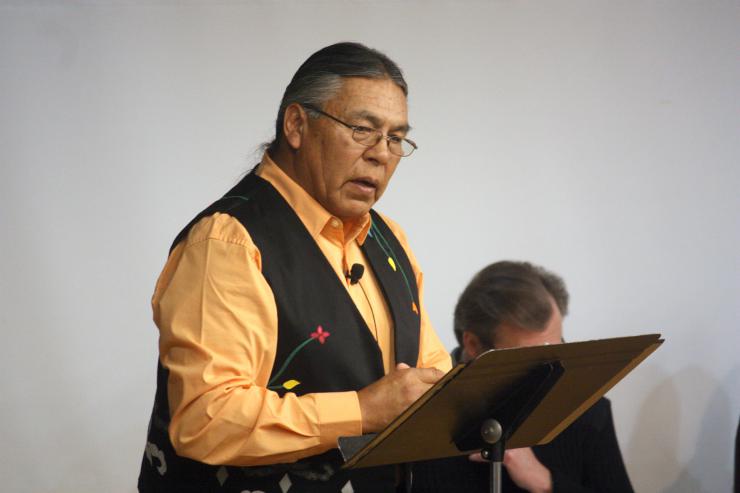

Much of my work has been dedicated to the advancement of Native religious freedom and protection of sacred places and ancestors. I was so honored that my work was recognized when I received a 2014 Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama. As with all life achievement awards, and especially with this highest US civilian honor, one is acutely aware of the arcs of life work. I am so pleased that I am not the first Native or Native woman recipient of the Medal of Freedom—Dr. Annie Dodge Wauneka (Navajo) was in the first group of awardees in 1963—and I am the fourth Native person to receive this honor.

This is how it is in the performing arts today. We are long past the “first” or the “only” in most categories. Granted, even though Native People worked in films from the earliest days of filmmaking—my mother’s grandfather, Chief Thunderbird (Cheyenne), was one of them—it was nearly a century before Smoke Signals (1998) came out, the first film by a Native director, Chris Eyre (Cheyenne and Arapaho), with a screenplay by a Native writer, Sherman Alexie (Spokane/Coeur d’Alene). But since then, it’s been hard to keep up with the new work by Native filmmakers, and the up and comers will find it hard to match the films of Sterlin Harjo (Seminole/Creek).

It’s heartening to see the myriad talented Native theatre and film people working today. However, the Bloody Bloody example remains a cautionary tale, in terms of where we have been and where it’s easy to get stuck, particularly when we are not in charge or when we aren’t being heard.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

It seems that "Michael" and "qwerty" are connected with the work and provide insider emphasis and meaning that do not appear on the stage in any proportionately effective role They sound like the kind of inserts that are designed to respond to criticism. It's interesting that one of the two disinterested audience members assumed that my critique resulted from an angry predisposition. I went to the performance having heard about the contentious meeting -- where those responsible for BBAJ did everything but spell "satire," as the Native pros were saying "bad theater" -- and with decades-long love and respect for the Public, which I thought would fix what was wrong with the writing, directing and performing before sending it to B'way. If anything, I was prejudiced in favor of the Public's keen sense of what works on the page and on the stage, and the good sense to listen to the New York Natives in theater about both the Indian stuff and the theater stuff. I don't know what went wrong, but the result was terribly disappointing -- just ask the B'way audiences, who gave it a collective "stinko."

Naturally people are entitled to view any work of art as it strikes them, but I loved Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson for its depiction of horrible people tricking the public by using populist jargon (and music) to make their actions appear cool. There isn't a white male character in BBAJ that's likeable, but we're watching the story being told as Jackson would have it told. That's why early on in the musical Jackson kills the narrator who's telling the truth so he can have control over how he's depicted. The joke is how he sees himself as a noble victim. I take the show as a cautionary tale to look beyond the glitz and educate yourselves about what our leaders are doing.

I'm fascinated that we both came away from one production with such opposite opinions - it verbatim calls Jackson "an American Hitler" and the arc of the play is predicated on how haunted he becomes with the atrocities that he commits. It is not some sort paean to this brutal era of American history, it mercilessly mocks Jackson and the racist public that elected him a la "Springtime for Hitler."

Furthermore, the works is not solely content to rest on criticizing dead white men - I believe the play's intention was to lay these horrors at the feet of contemporary Americans. One moment has characters discussing their misgivings towards (and ultimate acceptance of) living on land that was violently seized from Native peoples. This was done with contemporary speech, full of "likes,""ums," and other 21st century affectations that clearly point the finger at the audience. If that wasn't clear enough, the last song, "Second Nature," spells it out extremely plainly for us:

"The grass grows, a prairie

A wilderness across a continent

And we take it

We clear it out and make it

In our image

The backyards, the driveways

The covered wagons rushing

Through the high planes,

The motels on the canyon

They make a second nature"

I'm not sure how anyone can interpret it as anything but a haunting reminder of America's continued complicity in the genocide.

You have extremely valid issues with elision of Native voices on this or

any other project. Redface, like yellowface, is infuriating.I notice that you really discuss very little about the play itself. You've quoted one song without discussing its context - "Ten Little Indians" is interspersed with disturbing scenes depicting the breaking of treaties and the extermination of individual tribes, but here you've depicted it as an act of mockery. Please engage with a work on its own aesthetic and dramaturgical merits - it sounds very much like you decided to be outraged before you saw it. It reminds me of a Filipino hearing about "Here Lies Love," deciding that a disco musical about the Marcos regime can only be deeply insulting, buying a ticket and then waiting for their expectations to be confirmed.

Susan,

Thank you for writing this informative, important, and powerful piece. May the ripples of its impact propel, clarify and expand reader's consciousness and actions to this relevant issue.