Conversation with Playwright Jackie Sibblies Drury

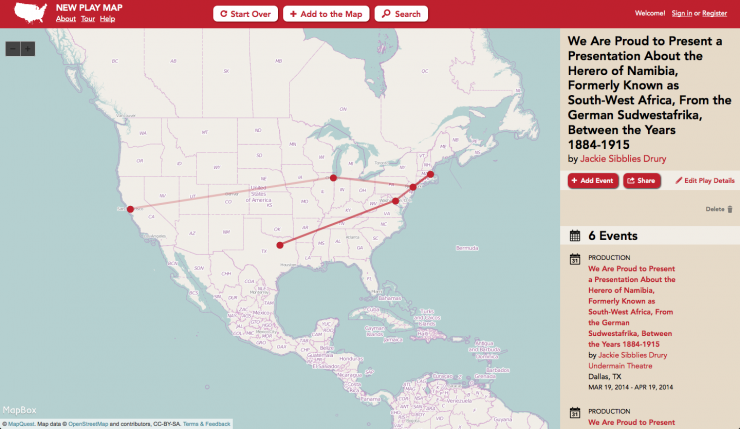

View this play's journey on the New Play Map.

The following is a transcript of a post-show discussion with playwright Jackie Sibblies Drury for the Boston production of We Are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 which is a current co-production between Company One and ArtsEmerson. This event was livestreamed, recorded, and archived on Sunday, January 19, 2014 using the global, commons-based peer produced HowlRound TV network at howlround.tv. The transcription was produced by Nancy Vitale.

Ilana Brownstein: Jackie, I wanted to ask you to start us off by giving us a sense of how you came to playwriting. What is it about this form that attracted you? Were you always a playwright? Did you come to it late? What was that for you?

Jackie Sibblies Drury: I think that I didn’t come to playwriting. I started off as an actor, which is what most people that work in theatre do. No one has the opportunity to write a play in their elementary school, but everyone gets to be in a play in their elementary school. I acted a bunch in college, and moved to New York, and realized that I could not...that I was not really cut out for that kind of life. I looked at the first advertisement for headshots, and saw how expensive they were, and I was like, “Nope. Nope.”

Laughter.

So I sort of lived in New York, and kicked around, and helped friends with shows, and did all kinds of odd jobs, and started writing mostly for myself. And eventually realized that I really liked using characters to explore ideas. And ended up applying to graduate school, because I felt like I needed someone to tell me that I had learned how to be a playwright, and had given me some sort of, I don’t know – Oh yeah, I guess it’s called an MFA, which tells you you’re allowed to be a playwright.

Ilana Brownstein: Can you talk a little bit about how it is you came to write this play.

Jackie Sibblies Drury: I was trying to research a very different play, where I thought...sort of a play based around this actor who is the son of this German woman and an American GI. He always plays an American GI in these 80s Fassbinder movies. I don’t know why I thought that would make a good play, but side story...

I was just trying to find more information about him, and I just Googled “Black people plus Germany” to see what would come up. And there was a bunch of hits about genocide, the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. I hadn’t been familiar with it at all. I didn’t know that Germany had committed genocide before WWII. I didn’t know that Germany had any African colonies. I didn’t realize that any of that had happened. I guess this is really arrogant, how surprised I was, because I was like, “I’m not an idiot. I have taken a history class. I know a little bit about this.”

So I started doing research about the genocide. Then I went to graduate school, and was sitting on this stack of information, and tried to write a play about the Herero Genocide as my graduate student thesis.

That play was really terrible. Yay, terrible plays. I had a reading of it in the middle of the semester. And I was like, “oh no, how am I going to graduate? I need that paper that tells me I’m allowed to be a playwright. Oh, no!”

I freaked out. Got more and more interested in the ways in which I felt the play was failing.

I introduced this meta-theatrical element (the big M-word) that allowed a group of actors to struggle with a similar thing that I felt I was struggling with – in trying to capture in this story.

Ilana Brownstein: So, your development process obviously began with the failed play. And then moved on to the version that you submitted to the Ignition Festival. Can you talk a little bit about how you got from that first version of the play, which has a very different ending from the one that those of you who are sitting in this room saw tonight? How did you track the path? Can you talk about what the differences were in the first draft versus now?

Jackie Sibblies Drury: I think that when I was in graduate school producing the first draft of the play that you saw at this festival in Chicago... In graduate school, in the sort of workshop production thing that we did—which just means that there’s designers, and stuff, that we’d produced it for 2 or 3 shows—the play had slightly different endings every day in tech and in the production. I was having so much trouble trying to end this...or what happens in this moment of where the play breaks.

I don’t know why so much of this process was failing miserably and publicly over and over again. We tried different things. We tried having a moment, where the actors walked forward and said their names, their actual names. But that ended up feeling like some sort of weird PSA for some sort of disease from the 90s. It was just awful.

I did some workshops of the play with the director Eric Ting, who directed the first production of the play in Chicago and the second production in New York. He and I had a really close collaboration. I remember doing a workshop in Chicago in the middle of a blizzard that about three people saw because of the blizzard, and trying the very first version, iteration of the ending that was what you guys experienced, and what I had been working with. There’s something about giving a lot of opportunity – and no language – an opportunity for the actors to have a reaction to the moment before the end of the play. There was something about it that just felt right. Trying to sort of have a resolution, or a more tradition resolution to the play, felt a little offensive to the shit that’s dredged up in the play. So any sort of “sad ending” felt like saying that, “Racism is sad. Genocide is Sad. I feel Sad.” I can leave, and go get a sandwich.” But I wanted to—sandwiches are delicious—but I wanted to allow for a different kind of interaction with the ideas in the play.

Ilana Brownstein: So for those who don’t know, the original ending also had some more catharsis for both the actors and the audience. That it found some places where maybe the audience was able to walk out and feel like, “Oh, that was rough, but, ok, we’re going to soldier on.” But I think now the ending—and for those who are watching on our livestream, who maybe don’t know the play—it ends in a very non-traditional way in which there isn’t a curtain call per se. Certainly the actors appear later, and we acknowledge them whenever they arrive in the lobby. But in the space, it is a place where there are still questions. It feels, in some ways, unfinished.

Can you talk about how you and Eric Ting worked to get to this version? And it was the same version that was at Soho Rep last year. For you—as you were thinking about how the audience leaves the experience of this play, which has such drastic pendulum swings between comedy and some really dark places—what were some of the important things for you as you were thinking as both a playwright and actor originally to get to this version of the play?

Jackie Sibblies Drury: I think for me a lot of it is based in my own experience of seeing play and being...a very deferential person and nervous person. When I am personally made uncomfortable in a situation, I want to make myself feel better and make the other person, who made me uncomfortable feel better almost immediately by making a joke, laughing the situation off, being ironic about it. And I wanted to free the audience and the performers of that need to make everything ok, because it’s just not ok. Allowing that was really important to me.

Now I’ve made myself a little uncomfortable, and I don’t remember what the question is. Sorry.

Laughter.

Ilana Brownstein: No, that’s fine. I think you answered the question. So, I’d like to take an opportunity to open this up to our audience, our actors, our collaborators, Summer and Ramona, and give them a chance to ask you some questions and maybe vice versa. If you have some questions for our audience, you can ask them.

Audience Member: This is a question for Summer about the ending. As a director, how did you navigate helping the actors find their way through that ending of the play?

Summer Williams: Awkward, because they’re in the room. Don’t say anything, guys. So one thing I said was, “there’s only so much of this that is directable, right? We’re trying to get to the center of something. I can only talk you around the center of it, and you’re going to have to figure out how to enter it yourselves. I, throughout the process, have been asking them to be really transparent and be really naked, and to be vulnerable enough to be the most naked in that moment, especially when it’s difficult. There are things that are very specific that have to happen, right? One, Three and Five can’t notice Four too soon. That’s a very practical thing. Four has to reset the space in some way, shape or form. There are critical pieces that he needs to make contact with and engage with so that we in the space can feel that moment, right? It’s important for us to watch him start to break down the wall. It’s important for us to see him pick up the chain, pick up the paper, to take down the noose. It’s important to watch him pack that stuff up in the chest.

Outside of that, it’s them. And it’s what happens in that space, their feelings in that moment, with each other and with all of you. And what you, you being the audience, do or say in that moment greatly influences what that moment is. There are times when Actor Four, played by Mark... There are times when I’ve seen people extend their hands to him. I’ve seen people hug him. I’ve seen people speak to him in the moment when he’s trying to speak. And that is something that he has to deal with in the moment, and be open enough to allow himself to feel that. So, it’s a tall order. There is nothing about this that is at all easy for them.

Ilana Brownstein: Thank you for that question. Joe Kidawski, one of our actors, has a question.

Joe Kidawski: Hello! We as a group spent a lot of time talking about, and trying to create a space, where we were comfortable enough to allow ourselves to say something that might be offensive, or to create a space where it might be ok to just sort of jam our foot as far into our mouth as humanly possible. And I was wondering about your process of creating a space that was comfortable enough to say these things. It might not be the same for a playwright, but I know as an actor, you have to own these things that you’re saying, even if they don’t exactly reflect your personal opinions. You have to find an ownership for them in the space. And I’m wondering if you had to deal with that “I can’t say this...”

Jackie Sibblies Drury: That’s a good question. I think... I don’t know. In that way, I get to feel incredibly optimistic and positively hopeful about the people the artists involved in making the play happen, and so much of it is dependent on the direction, on the performers themselves. I didn’t realize—as I was writing the play—I didn’t totally fully realize that it was going to be produced. I honestly didn’t think about it at all. That was dumb.

Laughter.

What I’ve come to really appreciate and respect is that as much as the play sort of mocks the process of a devised, collaborative theatre company, it also forces groups of individuals to create a collaborative and devised theatre company and be successful at it—much more successful than the characters are, while also hewing much more closely to who the characters are. So it’s a super ironic complement, I guess to the theatre.

I wasn’t there for the rehearsal process at Company One, obviously... You know that. But when I was involved in previous rehearsal processes, and I was talking about this with Eric Ting yesterday, about how even the audition process was really different—especially for him, because he has directed a lot for a bunch of regional theaters, where you have actors come in and read a part of the play. That’s a normal way to audition people. Come in and sing a song.

And for us, we had people come in, and we had an interview, where we asked them—maybe assaulted them—with personal questions. I firmly believe that, strangely, the only requirements for the performers in the piece are that there’s three white actors, there’s three black actors, that all the actors are good at—are smart people, that can empathize with the character. I don’t think someone has to be 5’2”, or have medium-olive skin, that there’s no specific requirements besides generosity, interest, and empathy. I get excited about the opportunity to let groups of people come together in that way.

Audience Member, Maggie: I really enjoyed your performance, or their performance. My question is, although this deals with—and in the title—it’s very much about the specific historical occurrence with which you are dealing with. But to me, it felt like a very American play, and it felt like, a lot of times, especially because of the conceit in which you wrote it, it dealt with American, inherently American, issues. I’m sure it’s something you took into consideration, but exactly how that came into the process as it unfolded through the writing of it. Because you started with the nugget of the idea, and it took off from there.

Jackie Sibblies Drury: I am very aware of the fact that someone who is very interested in finding out something about the Herero, that this is an incredibly disappointing play.

Laughter.

You actually learn more from the Wikipedia page. Actually. I also, as I was swerving into this—whatever the thing that you saw is—that I was hyper aware of the fact that in some ways I was just using their story to tell a different story. It could be seen as incredibly offensive to boil someone’s—this huge atrocity down to an example of something, and point at it and not investigate it. But I also think that because I’m not a historian—this sounds like a cop-out, and I don’t mean it to be–because I’m not a historian, I did a bunch of research about the Herero, and I just felt completely incapable of creating a piece of theatre that would somehow speak for these people. So I did feel I was equipped to tell a story about America and contemporary race dynamics.

I take solace in the fact that even though the play is ultimately not about Africa or about Namibia or about the Herero, specifically, it is at least exposing people to that history. I’ve had the chance to talk to a couple descendents of the Herero who came to see various productions of the play, which was terrifying and incredibly exciting. Talking with one couple in particular and their children, there were excited that it was finding a way for American people to connect to this story, and to learn about it, and be more interested in, and be able to go out, and do some research about it, and learn about it. And that has been gratifying.

Ilana Brownstein: This is a question about the accents and about how they move through the play. Summer, do you want to take that?

Summer Williams: That’s Jackie, in terms of the drifting into the American South, and the way she sets us in this kind of netherworld all of the sudden between investigating the germ in the Herero situation and doing that by way of exploring what the black/white dynamic is in the American South. There’s a really lovely kind of not identifiable finesse that happens in the moment between those two actors as they begin to slip deeper and deeper into it, which feels generous and organic and tells the story really well. But that’s Jackie’s genius.

Ilana Brownstein: One of the questions we’ve had at a couple of our post-shows is where the accents happen and why. I don’t know if you want to talk about your thoughts about that.

Jackie Sibblies Drury: Pinpointing exactly where it happens is something that is up to Summer and the performers, but the scene it happens in is this longer-form improv that gets a little murky between the black-man actor and the white-man actor. To me, it happens there because it’s at a point in the play where the actors are committing more to the process in terms of how they’re investing in the characters. It’s coming from their own imagination rather than something that they are trying to fulfill externally. It’s something that from inside rather than pointing and trying to become something else. They, in my crazy brain, they subconsciously see the dynamic which they have, which is this sort of black/white dynamic, and subconsciously and immediately layer onto it the most recognizable version of that black/white hostile dynamic.

Ilana Brownstein: For those who haven’t had a chance to read the interview in the program that Ramona did with Jackie, Jackie you say something in that interview about how you yourself felt a similar kind of recognition, when you were looking at photographs of some of the Herero—you saw documentary photographs of them hanging—that you made a connection yourself to the American South. It’s interesting to me that, night to night, our actors have to navigate that exact thing that you were talking about.

Audience Member, Andrea: So, one of the things that I loved was when one of the characters took on the persona of the grandmother in relation to the image that the other actor saw, and talked about that you can’t walk in somebody else’s shoes. And it was very acute to me carefully watching how that character transformed into a perpetrator of sorts. Then I felt that was kind of dropped, and then we watched all the characters become either perpetrators or victims of sorts.

I was just struck with two things: one of them is that in my deepest heart, I hope and I believe that all my work is predicated on this notion that there are a small percentage of humans, the species that we are, that actually are able to look at and be accountable and say “no.” And I found that really interesting that you left that out. And so that as we watch the actors workshop and improvise themselves to the point that they were walking in what they imagined someone else’s shoes to be that option wasn’t a part of the palate at all. And I just wondered what you’re thinking about that.

Jackie Sibblies Drury: In reading about genocide or thinking about genocide, a big part of it it feels ridiculous to me to pretend like I’m some sort of expert on genocide, but we’re just going to roll with that for a sec. It seems like it’s not about one evil person making a decision to be evil. It’s obviously about a community; everyone in the society is implicated in the extermination of a section of that society. That’s just... So to me, there is no “No” if you’re a part of a system of oppression in that way. I also think that in a very different way, so much about the art of performance and the art of theatre is about never saying “No” to anything. I love improv, but I’m making it sound like, that people say it super ironically and with an eye-roll, “he played yes-and.” So your collaborator comes into a room and they’re asking you to do something wrong and stupid, but you don’t say that, you say, “yes, and” try to add to, instead of...

I think that as scary as complicity in a system of oppression, I think that investment and openness is beautiful in theatre—that there’s something interesting about complicity and this “yes-and” about live performance and of the audience, and of suspending disbelief and all of this. I’m not trying to draw a relationship, or some sort of one-to-one, but I think that those things fit together. So I think it’s right to not have anyone say “no” or stop until the play breaks.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

"And ended up applying to graduate school, because I felt like I needed someone to tell me that I had learned how to be a playwright, and had given me some sort of, I don’t know – Oh yeah, I guess it’s called an MFA, which tells you you’re allowed to be a playwright -" I understand that perhaps in someway Jackie was being ironic - and it was one of those very in the moment - jokey kind of things. But I still find this comment deeply troubling on so many levels.

Okay. So I went to sleep, woke up and now I feel like a jerk. After a good night's sleep here are three things I believe. 1) I read way to much into what Jackie said and put my own spin on it. 2) I am still troubled by the MFA stat but not by Jackie because she seems really cool, and I can't wait. to see We Are Proud to Present when Undermain Theatre does it this spring - Dallas Theater plug. 3) I think the MFA thing is still a button pusher for many. How do we address that and get past it? It seems like we always talk past each other.