Democratizing the Arts, Aesthetic Practice, and the Relationship to Community Change

A Conversation with Roberta Uno

P. Carl: You have been an inspiration to me in the past couple years—the impact you’ve had, the ways you continue to reimagine your own interventions. I’m wondering if we could talk a little bit about your very hybrid career—you’ve been a teacher, a scholar, a director, dramaturg, an artistic director of New WORLD Theater, a Ford Foundation program officer. How do you describe your own evolution as an artist, a thinker, and an innovator?

Roberta Uno: You know Carl, I’m not a person who ever thought about making a career in any of those fields. I always really thought about making the world that I want to live in, and that may sound really idealized, but as a woman of color and specifically as one in the Asian-American Pacific Islander category, one encounters incredible marginalization and even invisibility. I used to laugh, because my kids would play this game where they’d ask people, “If you were a superhero, what superpower would you want?” and when people said invisibility, I always thought, “Ah…right—I already have that superpower.”

I just started making theatre, and making the community that I wanted to live in, and many, many years later, people described that as audience development, or community engagement, but for me it was about making a world.

When you encounter that type of invisibility, it’s also a space to imagine, so I started making the work. I have a community organizing background—I worked for the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee when I was in high school. So I just started making theatre, and making the community that I wanted to live in, and many, many years later, people described that as audience development, or community engagement, but for me it was about making a world. And I didn’t find many texts when I looked at the canon, so I began to write and edit and document.

Carl: From the very beginning you’ve been doing these anthologies and excavating voices that have gone unheard in our field. Can you talk a little about that?

Roberta: When I studied theatre in college in the mid-1970s, I didn’t have any texts that had any Asian American or Pacific Islander voices in them. There was that wonderful Black Theatre USA: Plays by African Americans, edited by Ted Shine and James Hatch, Paul Carter Harrison and Ed Bullin’s work, and Doris Abramson’s book on black playwrights. There were some texts, but definitely my theatre education was like practically everyone else’s. The only reason that I knew any different was that I was born in Hawaiʻi and grew up in Los Angeles, so I grew up under different tutelage, seeing people like Mako of the East West Players—he was one of my mentors—and plays at the Inner City Cultural Center where C Bernard Jackson was already pioneering the type of multiculturalism that followed in the theatre.

When I founded New WORLD Theater in 1979, I also started teaching. I had photocopies of people’s plays, and I realized, “Maybe I should start actually creating some type of contextualized anthology so people could understand the perspective behind these works.” So that’s the publishing part. All of the work I’ve done has stayed in print. My publisher in the UK, Routledge, recently asked me to revise and create new editions of three of those collections because the number of students has actually increased because of the changing demographics, so this is a perfect refresh moment for those collections to include new voices. Two new editions of Monologues for Actors of Color will be out soon on Routledge; I’m also working on a new edition of Contemporary Plays by Women of Color.

Carl: It’s amazing—very few of those kinds of anthologies stay in print that long, so it’s a testimony to the fact that you’ve been filling that gap for a long time.

Roberta: The work that we were doing at New WORLD Theater was ahead of the curve of where America was going; ahead of the curve in terms of a multi-race, multi-ethnic approach. I think the issue of difference was something that we ascribed to the fact that we weren’t just holding hands and singing kumbaya—we were really pushing up against the notion that people can be siloed into reductive multicultural categories.

One has to use the power that one is given to change and transform things. The question for me was really, ‘What does it mean to take my values and experience into this arena that actually has the power to shape policy and national practice?’

Carl: You’re really ahead of the curve in a lot of your thinking. You’ve just come off twelve years as a program officer in the arts at the Ford Foundation. I always think of that as a great listening job where you get to hear from people all over the field. I’m wondering how that work of intersecting with so many diverse artists has influenced your thinking. How would you encapsulate that time at the Ford Foundation?

Roberta: To be honest, I never wanted to be in philanthropy. I was really happy before I was recruited. But I felt like it was a moment when I just couldn’t say no. One has to use the power that one is given to change and transform things. I went from running a small/mid-sized theatre in a small corner of New England to having a national platform and national responsibility. The question for me was really, “What does it mean to take my values and experience into this arena that actually has the power to shape policy and national practice?”

I think you’re right in describing that as a kind of listening and learning, but I also felt it was a place of activism. I did not see my role in philanthropy as passive—I tried very hard to create transparency and accountability. That is easier to say than to do because transactional relationships are based on who has the money. A colleague told me early on, “As long as you’re at the Ford Foundation, everything you say will be brilliant, because at the end of the day it’s a transactional relationship.” Many grantees who worked with me talk about how much I pushed them in the sense that doors could be opened or closed based on how they would walk through them, and based on the case they made for the larger field.

Joan Shigekawa at the Rockefeller Foundation taught me to ask grantees, “Who else do you think is doing this kind of work, who do you look towards for inspiration, and who are you learning from?” When I encountered people who told me “Nobody else does what we do,” I would think, “Wow, they are pretty isolated.” People who are very connected to others and have generosity is part of the world I want to live in.

I ultimately saw that job as a kind of community building—how do we actually work in these arenas, not just to strengthen our own practice but to build a larger community towards social change, social justice, and cultural equity issues?

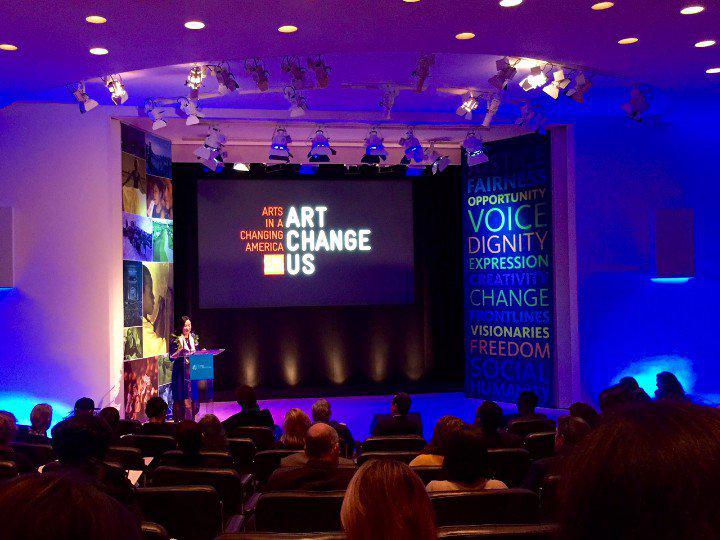

Carl: That community building you’ve been doing over time is really coming into a new venture of yours, Arts in a Changing America—ArtChangeUS. You talk about this initiative as reframing the national arts conversation in the intersection of arts and social justice. Could you unpack that for me a bit: what frame have we been working in, and what does a reframe look like for you?

Roberta: Arts in a Changing America is a five-year project. I see this moment of demographic change in the United States as something that will forever transform this country. People are aware of this change. Wherever they live, some aspect of the population shift has happened. It seems to me the United States is either going ahead into the future and becoming more connected to the world and to a global community and a type of global citizenship within our own country, or this is a time of retreat into a narrower, Balkanized, and ethnocentric America.

There’s an urgency to reframe at this moment because, first of all, reframing is happening on a large level. But within this big arts conversation, I think the frame that we’ve had to look at has been both advanced by and paradoxically diminished by multiculturalist policies of the last century. The multiculturalist framework was always about representations: black history month, and Asian American history month, and Caribbean week… This is awesome because we need to celebrate, but it’s also reductive.

How does that change when we’re thinking beyond inclusion into an existing dominant culture paradigm? We haven’t made progress in integrating many institutions—they have remained very nondiverse. Many places have actually resegregated—cities like San Francisco and others that are losing their populations of people of color. So this is an effort to say, “How do we evolve the framework in the arts to think beyond inclusion?”

A lot of that is why I started Arts in a Changing America, and why we are based on a model of fifteen core partners. It’s modeling new millennium thinking. We are saying this is five years: we’re not building a building, we’re not building a 501c3 to last forever. We are meta-organizing.

As we think about these new frameworks, we’ve tried to reframe even the focus of demography. We’re not social scientists, we’re not counting numbers of people and making assignments of resources; we actually try to blow that up because demography can marginalize people and populations that don’t have large numbers. You’ll very rarely hear demographic presentations that include Native people. So from our very start, we deeply inscribed Native and Indigenous leadership within our programming and co-partnerships.

Carl: Another question I have around Arts in a Changing America is about leadership. As I look around the national arts landscape, the leadership continues to look very much the same across the board, with little pockets of promise. How will this initiative be a catalyst for change?

Roberta: Something that I learned at the Ford Foundation is that it doesn’t really matter what the budget size of an organization is, but around this issue of cultural equity and social justice there are learners and there are leaders. It exists in a spectrum of practice. So again with the core partners, the idea was to really start with recognizing that leadership. These are fifteen people who—yourself included, Polly—have thought in innovative ways about democratizing the arts, about aesthetic practice, and about relationship to community change. If you look at our list, it really runs the gamut—some are academically-based, some are very large arts organizations, some are very small, many are artist cultural practitioners themselves.

It’s about trusting those theatremakers, those performance-makers, those art-makers, those social change-makers to be able to bring what they have amassed into a much more elevated, connected national platform.

Carl: The events themselves, from my experience of them, feel like a place where there are people who have been in the trenches for a very long time, but there are also fresh voices around the changing leadership in the theatre structure.

Roberta: Absolutely! I don’t know if you’ve noticed the Art Change US team itself is very, very young, and that was really intentional. We also felt that it should be led by working artists, so Kristen Calhoun and I are both working artists, but she’s of an entirely different generation than I am and many of the team are of even another generation.

Going to this issue of language, a lot of language around next generation is emerging leadership and emerging community, but hello! They’re here. These to me are now generation leaders; these are future conversations happening now. We don’t have to wait for a next generation—they’re actually in the room with us. But do we make space? Do we listen? How do we share that intergenerational mutual responsibility that we have and the joy of that?

For me, a huge part of that reframing has been as basic as language. When we tell people one thing is ethnically-specific and one thing is mainstream, the changing demographics begin to completely shift that kind of inequitable language. If you’re in a city and you refer to the mainstream, and yet the population has already shifted to 70 percent people of color, what is the mainstream? In so many grant applications and descriptions, people describe culturally-diverse organizations or people of color-predominant organizations as “ethnically specific,” and yet there are organizations that will have a pretty homogenous white board, staff, leadership, and even audience, but they aren’t labeled as ethnically-specific or racially-specific. How do we use language that isn’t code for the status quo?

Carl: You did that, Roberta, in one of the convenings I was at where you were talking about the terms majority and minority and how we are misusing that. Maybe the book for you to do next is one on language.

Roberta: I was speaking recently with a black faculty member who’s in a very, very white department (which is all over America), and he was saying, “What can we do to bring on more minority faculty members in my department?” I was listening to him talk and realized that he teaches in a school in a city that has already made that flip and a state that has already made that flip and yet he was still perpetuating that language. And I said, “Maybe you don’t want to use the word ‘minority’—maybe you want to talk about future faculty, people who actually relate to the future of America.” Then maybe people won’t see inclusion as an act of goodwill—it’s not medicine to take. It’s not your missionary duty in terms of a moral stand.

It’s actually something that corporate America gets, that the military gets, that many other organizations that function within a kind of American context realize: if you’re not relevant to the future of America, you won’t be able to function—whether that’s theatres building audiences or organizations building boards or staffs or curators and artistic directors making programming choices that need to be relevant to the future, to the globe, to the world. Whether the world is what we want it to be or not, it is here. The future is here. I think that’s where we need to change the conversation.

Carl: Arts in a Changing America is doing a REMAP convening April 15 and 16 at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, and HowlRound’s going to livestream. I’m just wondering what’s on the agenda for that convening; what do you hope to accomplish?

Roberta: One of the things we do is bring people together in real time and then share it through livestreaming in these REMAP events. In addition to the event in San Francisco, we also have another REMAP event we’re looking at potentially in Detroit and then another partner event in Dallas.

At REMAP we bring about two hundred people together in real time. We want to make sure that we don’t exceed a number where we won’t be able to have smaller conversations. Wherever we go it’s about 50 percent artistic and idea producers from that place, and about 50 percent from outside that place. We want to create a national conversation, but that is informed from the ground, from the place where our core partners are.

One thing we always do is lead with the art. We start with an immersive, experiential participatory arts experience that’s going to be led by amazing artists from all over, including people like D’Lo, the comedian and performance maker, Reggie Gray, the FLEXn dancer/choreographer from Brooklyn, Ananya Chatterjea, choreographer from Minneapolis, and many others. We want people to be destabilized, in the best sense, to not just come and be passive and think about things, but actually be activated. They’re already going to enter into kind of a pool of people that they might not have known. That whole concept of leading with the art is really important to us.

The types of themes that have been emerging for this particular REMAP are mostly area-informed, but also relate to national agendas of what is the change that’s afoot in this country. For example, we’re going to have a roundtable Surveillance and the Police State that Carlton Turner, our core partner from Alternate Roots in the south, will lead and it will have people like Hasan Elahi, the visual artist, and Jinho Ferreira, rapper, theatremaker, and law enforcement officer. You can get some of this information from our website. We have a session on Redefining Language through Identity. We have a couple of sessions that deal with the issue of gentrification and people being displaced—the resegregation of our cities. There’s one you referred to earlier, Changing Structures, Shifting Systems, which is going to look at that whole issue of how institutions change.

We are co-hosted by our Bay Area core partners, including Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and Youth Speaks, so we will feature new work by Grisha Coleman and close with the 20th anniversary Youth Speaks Poetry Slam, which will kind of exemplify this whole issue of creating space by taking over all of Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco with thousands of teen voices and poet performers.

Carl: It sounds just amazing, and I’m glad we’re going to get to livestream it for the folks that won’t be there. There’s just so much here we could talk about for hours, but I just have one last question. What feels like success for you when you map out five years of this work? How do you more broadly define success in the work that you’ve been doing over time?

Roberta: One indicator of success is that this experiment of bringing these fifteen core partners together happens and builds more together than we can individually. When people think of something like this, they say, “Oh, there’s an advisory board or a brain trust,” but for us, we feel it’s an indicator of success if the partners are actually brought together in collaboration around the programming and the design of the project and that their networks are strengthened and that their complimentary practices are brought into a conversation. From the beginning, when we thought our kind of strawman was, “We will do one annual REMAP over five years! We will do five of those!” that’s what we originally thought. Because of our partners, this has totally accelerated. We just did one in October, and we’re already doing one in April in New York City, now we’re going to the Bay Area, and it looks like we’re going to do another one the following October. So core partnership activation is one of our real indicators of success. If you look on our website, we have started to build this repository of presenters who have been part of what we did last October. It’s beautiful to see artists and cultural leaders like Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation, next to Alison Warden, who is an incredible Alaskan native performance artist.

I think the other kind of indicator of success is to what extent are our ideas engaged by others? Is there relevance? If we’re just doing the project ourselves, or even just with our wonderful partners, we might be in a kind of isolation. So the extent to which others have already contacted us to collaborate—such as the Aspen Institute, the National Immigration Integration Conference, Citizen University, and others—in and outside of the arts. The Kennedy Center is also very interested in a multi-year collaboration with us, so the creation of new models of equitable partnership is another indicator. And then the bigger one—the big, big one—the perception of changing demographics in the US changing from being a threat to one that is a cultural asset. I think if our art field can become even more relevant, then we as arts-makers can play a greater role in advancing a larger social understanding of equity.

Carl: I like that end point of thinking of our demographic shift as a cultural asset. If we get there after this particular election, that will be life-changing for all of us in the next five years.

Roberta: Other people have said, “Roberta, why are you doing this, you’ve been an artistic director, you’ve been a full professor, you were at the Ford Foundation—why and how would you imagine a start-up project.” But that’s just who I am. As theatremakers we have to be fearless about confronting the unknown.

Carl: I’ve personally already been able to see the impact that you’re having on the field and the conversation, so there’s much gratitude from my perspective that you’re diving into the start-up at this stage in the game. I hope for myself that the next venture I start will be as risky as the one I’m in now.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here