Developmental Through Lines

O’Neill, The Nether, and Bright Half Life

Like siblings who grew up in the same house at different times with different family members around, two plays recently concluded Off Broadway runs after being nurtured in the O’Neill Playwrights Conference, The Nether by Jennifer Haley and Bright Half Life by Tanya Barfield.

Jennifer Haley’s The Nether, produced by MCC Theater in 2015, explores personal responsibility for questionable moral and sexual explorations. Cyber-detective Morris (Merritt Wever) interviews businessman Sims (Frank Morris) and customer Doyle (Peter Friedman) about the Victorian-era cyber fantasy world Sims has created called The Hideaway where humans don digital identities and play out sexual fantasies involving children and violence. Virtual characters animate the fantasy world, including child object of fantasy desires Iris (Sophia Anne Caruso) and undercover investigator Woodnut (Ben Rosenfield).

Tanya Barfield’s Bright Half Life, produced by the Women’s Project at New York City Center Stage II, explores romance and social institutions with two smart women and fractured storytelling in an angular physical theatrical space. Love in the twenty-first century between two women who meet at work—Erica (Rebecca Henderson) is an overqualified temp and Vicky (Rachael Holmes) is her superior—marriage, children, a break up, a serious illness ensue.

Both plays push boundaries in theme and theatrical style. What follows are some reflections by the playwrights and O’Neill Artistic Director Wendy Goldberg.

The Nether and Bright Half Life Enter the O’Neill Process

The six-to-eight-member summer cohort of playwrights assembled each year at the O’Neill is in some ways, like a college class. “It’s important that people who are a part of what we do also have a range in experience,” noted Wendy Goldberg, O'Neill Artistic Director, about each season’s cohort. “I’m trying to put a community of artists together.”

Goldberg was already familiar with the work of Jennifer Haley and Tanya Barfield when she and her team finalized the O’Neill summer communities that eventually included Haley’s The Nether in 2011 and Barfield’s Bright Half Life in 2014. The 2008 Humana Festival introduced Goldberg to Haley’s fascination with the cyber world in Neighborhood 3: Requisition of Doom, in which suburban teenagers addicted to an online horror game encounter zombies and blurred lines between virtual and real worlds. This 2008 play won Haley a Primus Award citation in 2009 from the American Theatre Critics Association (ATCA) and in 2014 the ATCA awarded Haley with the Primus for The Nether. Goldberg had known Barfield since she was a Juilliard student and invited to a program Goldberg ran at Arena Stage for playwrights and their mentors—Barfield for a play reading and her playwright mentor, Marsha Norman, for a fully staged production.

The Nether at the O’Neill and After

The Nether presents modern online lives mashed with alternative life styles to explore what is private and what is public. Goldberg noted of Haley’s creation,

Everything we do on a daily basis has been co-opted or taken away somehow by computers. She’s taken our universe and looks not-too-far into the future, one of the reasons why the play is so incredibly provocative and allows us to enter into it relatively easily without having to stretch too far. It’s the uneasy side of all of the virtual life interaction that we have.

Playwright Haley sees The Nether as part of an “unplanned trilogy of technology plays,” along with Neighborhood 3: Requisition of Doom and Froggy.

The 2011 O’Neill cohort also included Deb Laufer’s Leveling Up about drone operators—creating a serendipitous theatrical conversation among the plays and their audiences that happens some summers. Goldberg mused that these artistic conversations don’t come out of a consciously created theme, but unfold on their own:

It was about educating the whole community about what we were looking at. I was so compelled by Jen’s play, really successfully wrestling with these questions of the dark side of virtual reality, and our culture’s obsession and our interaction and craze with it.

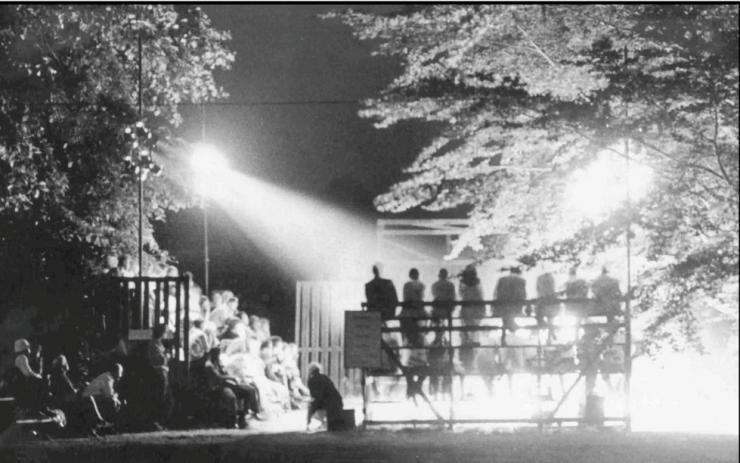

The 2011 O’Neill reading was held below towering beech trees at The Edith Oliver Theater, named for the dramaturg and critic long associated with the O’Neill. Goldberg recalled,

Those of us who had the opportunity to witness the play in that space—you could see its potential and start envisioning a fuller realized production. I think we all were just stunned. People didn’t want to move out of their seats. People were kind of uneasy and wanted to talk about it.

The Nether won the Blackburn Prize in 2012 after its work at the O’Neill and during its time with Center Theatre Group (CTG) in Los Angeles. During the O’Neill stage of the play’s evolution Haley experimented with a backstory about the Nether-based character Woodnut, the avatar for the real life interrogator character Morris. “I wrote out a whole backstory while at the O’Neill and then realized I could do that a different way.” She ultimately purged this labyrinthine idea built on monologue backstories after Neel Keller of CTG suggested Haley add the character of Woodnut, and repeated the advice after seeing a reading at Philadelphia Theatre Company. “Then I had to write that version. That’s what took a year leading up to the production CTG in Spring 2013. CTG gave me two workshops to start rewriting… That one note just made everything fall into place.” A London production opened in Summer 2014 at the Royal Court Theatre and transferred to the West End in Winter 2015.

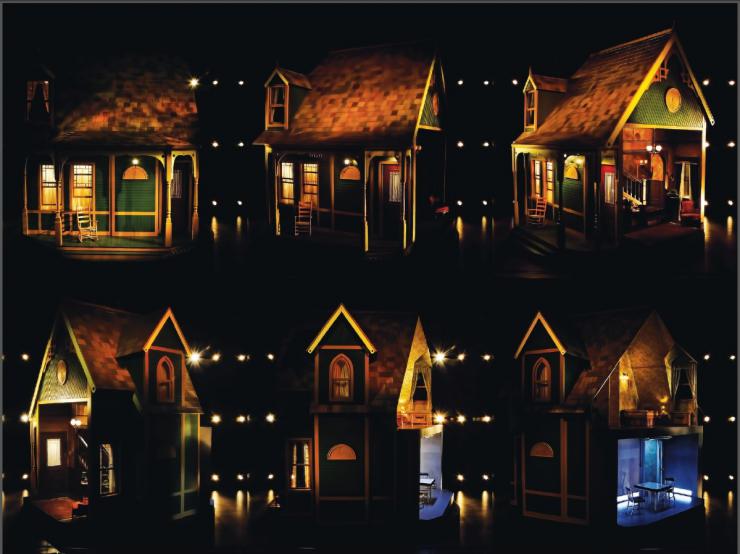

Production designs have varied dramatically—from a revolving dollhouse in 2013 at CTG, to digital high-velocity projections in the London designs in 2014 and 2015, to the hidden pocket doors that opened to reveal Victorian lushness in the 2015 MCC New York design. In the LA set, the interrogation room was below the digital child Iris’s bedroom. When the play started, everything was masked except the interrogation room so the reveal of the rest of the set was powerful. “Everything opened up,” recalled Haley.

The curtains pulled back, the curtain went up, masking pulled back, birds, sunshine, and you reveal this whole house. The house starts turning, and you can watch the little girl like look out her upper window and then watch her run through the house. Meanwhile Mr. Sims (the digital Hideaway creator) goes back into an interior portion of the house, and by the time the house is turned around to reveal the foyer, she’s running down the stairs, he’s coming out a door with his costume changed, and all of the transitions were just beautifully choreographed with this turning house.

Goldberg discussed the joy of discovering a play gem in an unproduced script pile, and the pride in watching the play move on.

We’ve just been so proud of everything that has happened for this play. I know that the initial design conversations were really informed for Jennifer, by what we first discussed at the O’Neill. How much of that world you want to see, how little of it, what should be surprising about it, what shouldn’t be, what’s the reveal, how do you go back and forth between the interrogation room and the Nether-space, what kind of on-line space we’re looking at. We did all of that under a tree at the O’Neill.

Bright Half Life at the O’Neill and After

Bright Half Life is a quietly potent tale of a romance told through fractured storytelling involving Erica, an overqualified temp, and her superior Vicky. Goldberg reflected on the 2014 O’Neill experience with this play. “That one closed this last season for me. I’m happy to have people leave the summer with a very poignant piece.” The non-linear storytelling was augmented in the New York production by a modernist unencumbered set. According to Goldberg, this production design began at the O’Neill. Rachel Hauck, the O’Neill Resident Designer (who also designed the New York production), holds a “dream design” meeting with each playwright to consider design possibilities for future productions after the O’Neill staged reading process. Goldberg recalled,

If anything in the development process, it’s terrific if we can all kind of get the original team together and that team stays together up to production, but we know that doesn’t always happen. When we find out that things are going to have a production and we have anything to do with it, we try to get the director who is attached and going to be moving forward with it. More often than not, the writer says, this is a first look and I want an opportunity for myself to explore deeper. I think having multiple conversations about the same piece with other perspectives is only a good thing.

The environment around us has become much more competitive. Everybody has a new play program... I just wanted our work to resonate and take flight all over, as much as it possibly can.

Through Lines and Summer Breezes

Goldberg described a dance the O’Neill conducts to keep their developmental process protected from commerce while seeking to place plays and playwrights with theaters for the next stage of their development. Some years that dance yields spectacular results. During 2014 and 2015 at least seven plays with O’Neill ties had runs in New York—one of which I explored here on HowlRound.

Some of this success can be ascribed to the teams and future life for O’Neill plays on which Goldberg spends much of her attention.

We try to build the team in the hopes that there will be some advocacy for the play beyond the O’Neill. I’m always thinking about those things as we work. It’s not been a big part of the O’Neill culture in the past. It’s something that I’ve been much more invested in because I’ve had to be. The environment around us has become much more competitive. Everybody has a new play program. People have ways in which they work on their commissions, which they keep in house. I just wanted our work to resonate and take flight all over, as much as it possibly can.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here