Dispatch from Tehran—33rd Annual Fadjr International Theater Festival, Part 2

In January 2015, I was lucky to be in Tehran, Iran and catch the first few days of the annual Fadjr International Theater Festival. Having taken a six-month sabbatical in Iran in 2010, I am hooked on Tehran’s theatre scene and try to catch as much of it as possible. In Part 1 of this article, I talked about two plays that premiered at Fadjr, Goftegooye Fararian (Fugitive Conversations) written by Mohammad Zare’i and directed by Milad Shajareh; and Parvaz bar faraz-e Shahr (Flight above the City) from Armenia written by Anush Aslibekian and directed by Narine Gregorian. In Part 2, I discuss productions that premiered outside the Festival.

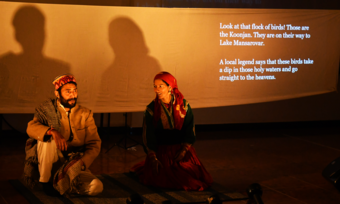

Khaneh-vadeh. Photo by Hossein Esmaeli.

The Fadjr Festival also presents a selection of plays that were staged in Iran during the past year. Some of the best work I saw was in this category. Khaneh-vadeh (The Family—spelled unusually, implies an implosion or a falling apart), written and directed by Seyyed Mohammad Mosavat, depicts an extremely happy and satisfied family. Everyone is dressed the same, smiles in similar exaggerated manner, and chews their happy (invisible) family meal around the table with the same voracious vigor. Then the father announces that he has purchased an airplane for the family, which is on display outside. The whole family lines up facing upstage to see the plane. We, the audience do not see anything. The family oohs and aahs incessantly and nods in satisfaction. Suddenly, the eldest son exclaims, “But I do not see an airplane!” And so with this simple “the emperor has no clothes” statement, begins the implosion of the family. The eldest son is excommunicated and is never spoken of again.

Khaneh-vadeh. Photo by Hossein Esmaeli.

The family resumes their charade, but the eldest son succeeds in connecting with the daughter and through her continues to challenge the family’s assumptions. His efforts come to a head during the younger son’s birthday celebration. Each family member presents the boy with an elaborately decorated, but empty, gift box. Ceremoniously each box is presented to the young boy who exudes joy every time he opens an empty box. Last, the daughter presents a gift box we know was given to her by the elder brother. The boy opens the gift box to find a large fuzzy golden duck (similar to an Easter toy. The actuality of the gift is too much for the family to bear and the whole celebration falls apart: grandparents run around the stage, the mother attempts, unsuccessfully, to reassure the despondent father, and the younger brother weeps; all the while the sister and elder brother try to calm the family and explain that there is no need to be scared of the truth. This reasoning falls on deaf ears. Khaneh-vadeh was expertly staged and performed by an extremely versatile ensemble fully committed to the piece’s grotesque aesthetic. The actors skillfully executed each moment. The performance was both deeply thrilling and disturbing.

Khaneh-vadeh. Photo by Hossein Esmaeli.

Ham-Havayi (Sharing-air, implies a super connection) written by Mahin Sadri and directed by Afsaneh Mahian brought together the real-life story of three ordinary Iranian women whose lives were propelled by extraordinary circumstances. Staged in northern Tehran, in the basement of a large villa that was converted into a cultural center, Ham-Havayi is set in a fully operational kitchen. In the process of telling her story, each woman prepares food: one bakes a cake, another a funeral plate, and the third a dish that requires much chopping of vegetables.

Ham-Havayi. Photo by Hadi Hirbodvash.

The play opens with a monologue by the wife of a jet pilot during the Iran-Iraq war; like everyone else, she expresses surprise by the pilot’s decision to fly his plane into a government building in Baghdad. This was in the 1980s, long before the events of September 11, 2001. The second character in the play is a teenager who meets her hero, a famous football player. Her innocent admiration as a teenager evolves when as a young woman she meets the footballer again and he returns her affection by offering to set her up (as a mistress) in an apartment. Their notorious love affair is thrown all over the news when the young woman, in a jealous rage over his wife, attacks and murders the football player. The third story is that of a young woman who yearns to climb K2. She trains for several years and has a few successful climbs of lesser peaks. Her attempted climb ends in tragedy when the team loses a young man who refuses to follow orders and proceeds to climb the mountain despite storm warnings. The women’s shared tragedies, self-inflicted or not, provide fertile common ground for dramatization.

Ham-Havayi. Photo by Hadi Hirbodvash.

The kitchen setting raises expectations of deeper connection and collaboration, possibly even meal-sharing. But the play keeps the three stories separate and short of a few meaningful glances, the three women remain dramatically apart. Perhaps my longing for greater integration of the three stories was unique, as audiences, particularly women, received Ham-Havayi with enthusiasm. I felt a deep sense of admiration by the audience for these women who were each unique in their own way and were tossed into the public eye unexpectedly, yet lived through their moments in the spotlight gracefully.

When I was in Tehran in 2010, discussions around private versus public funding of theatre were just emerging. Artists were fed up with government control of all aspects of theatre. Briefly, to make a production, one must first apply for approval of the play text. Once approved, it used to be that the government (Dramatic Arts Center of Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance) would provide full budget, marketing, rehearsal space, and performance schedule at an assigned venue. At that time, few theatre artists staged their work with little or no financial support from the Ministry and instead signed a contract directly with the municipality of Tehran that runs two venues of its own. The municipality has a separate budget for art and culture. It also provides some marketing support in the form of highway banners. Some artists worked strictly with the Tehran municipality and others produced work through private sponsors who provided advertising and/or financial support.

On this most recent trip, however, I was told that government funding of theatre had been severely cut in the last two years... Government cuts have forced theatre artists to seek private subsidies yet no incentives have been provided for individuals or private companies to sponsor the arts.

On this most recent trip, however, I was told that government funding of theatre had been severely cut in the last two years. Artists are now expected to self-produce with box office proceeds as their only source of revenue. Government cuts have forced theatre artists to seek private subsidies yet no incentives have been provided for individuals or private companies to sponsor the arts. Consequently, ticket prices have skyrocketed and production values have plummeted. In 2010, tickets at Teatre Shahr (City Theatre), Tehran’s main theatre venue ranged from 5-10 Toomans ($3-$5), while this year, the price range was 15-40 Toomans ($5-$13). The increase in pricing is less obvious when measured in dollars but the value of the Tooman has fallen nearly 400% since the economic embargo began in 2010. People are making less money (many benefits and subsidies have been cut) and prices have increased. This has made theatre, among other things, far less affordable for the masses. Now in 2015, the stages seem to be occupied by emerging theatre artists who are hungry for opportunities to create and show work. I saw little of the more experienced and established artists who are not willing to work without a proper budget and salary. Ironically, reduced funding has not meant less control over content. The government must still approve every play and production.

Ironically, reduced funding has not meant less control over content. The government must still approve every play and production.

One noteworthy new trend I observed is the private development of office or residential space into new performance venues. One such example is the Tamasha-khaneye Seh Noghteh (Dot, dot, dot theatre) where an entire floor of a five-story building has been turned into a performing arts space including a forty-seat black box studio, a tiny café, an open lobby space, an office, and restrooms. Workshops and theatre classes are also offered at Seh Noghteh, in addition to performances. Here, I saw the play,Bavar Konid Man Gregoir Samsa Hastam (Believe me, I am Gregory Samsa) written by Samiramis Babayi and directed by Arash Vahedi. This capably performed ensemble piece was reminiscent of Chaplin’s Modern Times. Centered on the “cog in the machine” plight of our age, the play began in a factory atmosphere established through energetic, militaristic physical movement performed by the ensemble in impeccable unison. Eventually, one laborer chooses to stand out but is immediately reported, investigated, and “corrected” in a series of mental and physical exercises. In a casual conversation after the performance, the young playwright explained how the play reflects the challenges of resisting the dominant culture—of choosing to stand out in the crowd. The director who also works as a filmmaker added how frustrated his generation feels with the lack of resources and unrelenting content control. Bavar Konid received several awards at the University Theatre Festival earlier in the spring including best costume design, best music, best direction, and best ensemble acting. The playwright and director appreciated the opportunity to self-produce their work, even in a small studio, but admitted that bringing audiences to a lesser-known space has been a huge challenge.

For those of us who occupy multiple identities, the physical shift from one country to the other can be a jarring experience. In Iran, when I introduce myself as the artistic director of a theatre company, people are often impressed. I think they imagine me running the Lincoln Center or producing on Broadway. When I tell them we have a tiny budget and I spend most of my time writing grants, fundraising, and marketing, they are baffled. These are foreign concepts in a country where the performing arts continue to be managed, funded, and promoted by the government. I envy their relative financial comforts, their packed houses. I love the heated debates that follow most theatre performances—walking into a dark and smoky café (yes, they smoke in cafés!) after a show and hearing the same play discussed from very different perspectives at multiple tables. But what I love most about theatre in Iran is that it’s in Persian. I can’t help my American colleagues hear the plays in Persian, but I hope I have succeeded in developing an appreciation in them (in you) for theatre in Iran.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

There is so much alternative venue theater here in the States -- it takes on a more resonant meaning in a country with a wildly devalued currency. To force open free spaces and talk within them about the overall story that people are struggling with -- it sounds like a vibrant form of political theater - living theater - politics - art mix. Thanks for the report, Torange!