Step One: Prevention

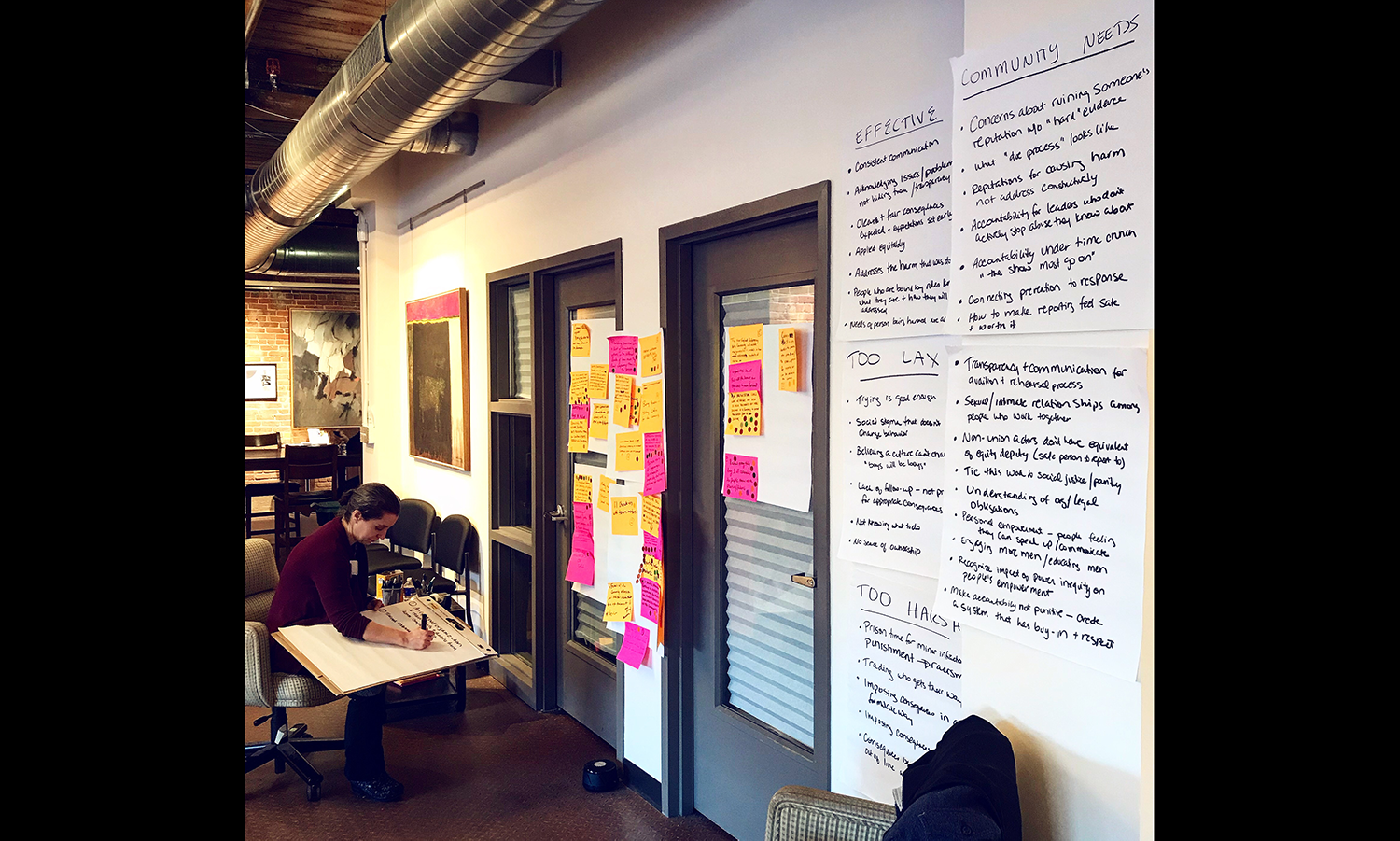

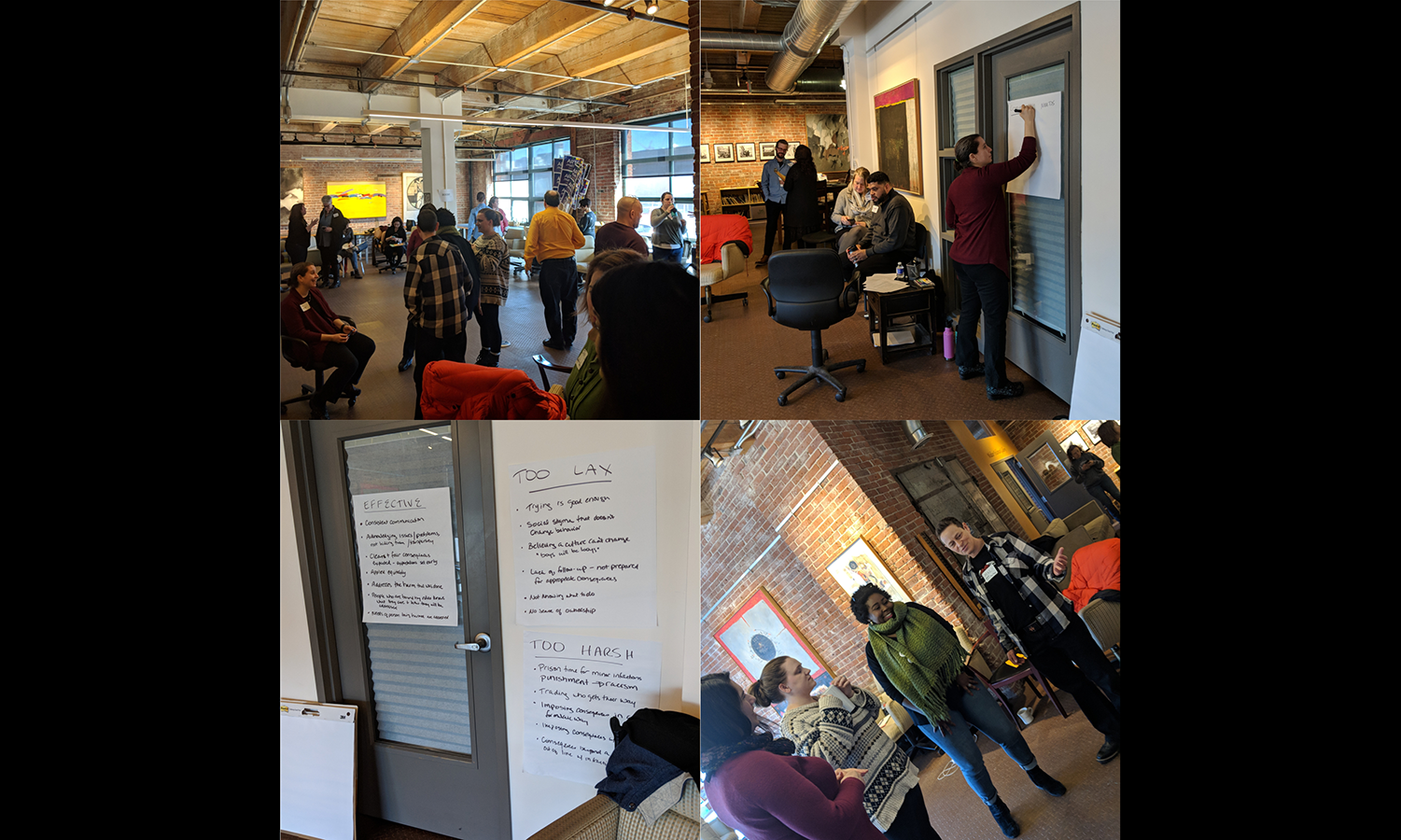

We called our membership to three brainstorming summits on the topic. Some people attended all of them, some just one or two, and some gave their input via surveys and online discussion. As a group, we all acknowledged our collective complicity in allowing continued harm—employing perpetrators and sweeping incidents under the rug—and thus our shared responsibility for solutions. While the work we did was community-focused and community-driven, what we uncovered was certainly not unique to New England.

During the summits, organizations shared resources, best practices, and horror stories. SpeakEasy Stage Company and Gloucester Stage Company (mid-sized companies with a budget around $1 million each) had just conducted major reevaluations of their own standards around harassment. Boston Playwrights’ Theatre and American Repertory Theater shared their resources as organizations working under universities with established HR systems, including Title IX (federal protections based on sex in education programs) and mandated reporting policies. Central Square Theater spoke about using an adaptation of the Chicago Theatre Standards, as developed by the Not In Our House movement, to address sexual harassment in Chicago theatres. Everyone shared their documents as models for the community, which StageSource shaped into templates for organizations to adopt and adapt to their needs.

Boilerplate harassment policies simply aren’t effective when the work sometimes requires individuals to change clothes, touch or kiss, and discuss sexual content with their coworkers.

In the brainstorming sessions, participants found substantial common ground among their roadblocks and needs. Participants asked for continuous bystander, intimacy, and related harassment training. This would ideally be done through a centralized source to give public and reliable credentials to artists and organizations.

There was also a desire for a set of harassment-prevention standards to be set across organizations. From that, we started drafting the Line Drawn Community Standards, which theatres would agree to and notify theatremakers of prior to hiring. This would provide freelancers consistency in terms of standards and recourse throughout the entire New England community. Standards proposed by the community included:

- Safety and responsibility supersede artistic, financial, or reputational goals

- Reports of misconduct will be acknowledged within twenty-four hours and include information for next steps

- Gender identity and sexual orientation will not be used to make assumptions about ability, talent, skill level, or performance ability

- Touch (by actors, directors, wardrobe, staff, etc.) will always be preceded by asking for consent

- Anyone who critiques an actor will focus on the actor’s work as a professional, not their appearance or identity as a person

- All employees will be held to the same standards of conduct. No one gets a “pass” because of age, donation amounts, reputation, or marketability

- Any nudity, intimacy, or touching required in a role will be clearly identified to the actor and all artists on or before hiring; it will never be added after hiring without the consent of the actor (note: there was variation of opinion by producers and artists on what this standard should look like—with some advocating for directors being able to add intimacy if it is supervised by a trained intimacy director)

- Intimate material will not be rehearsed without the presence of both a director and a stage manager and/or intimacy director

Each group felt strongly that solutions should be horizontal, stemming from survivor needs and desires—not top-down—and should include clear steps for moving forward after an incident is reported. Staff and leadership need to be trained in how to mediate and handle issues reported to them, and there needs to be specific training for mandated reporters—people legally bound by their profession to report instances of abuse to relevant authorities—on their responsibilities. We also discussed a system of reward, bringing attention to organizations that have taken definitive steps to curb harm in their milieu. A Line Drawn certification could be shown on their websites and marketing materials to help guide artists when choosing what companies to work for and to help guide audiences when deciding which productions to attend.

Each group felt strongly that solutions should be horizontal, stemming from survivor needs and desires.

Step Two: Accountability

Identifying shared values is vital, but we knew we couldn’t stop there. Harm has and will inevitably continue to occur. We also needed a system of accountability and recourse to remedy harm.

At our third community summit, we discussed two main approaches to accountability: restorative justice (survivor-centered and community-inclusive, with a possible goal of reintegration of the perpetrator back into the community) versus punitive justice (legal recourse with a goal of removing perpetrators).

With both approaches, participants mentioned they were scared of defamation lawsuits that might come from sharing information, and some feared McCarthy-era-like blacklists. Others protested they did not want to reintegrate perpetrators. Everyone was wary of, or under-informed on, relevant laws, and a lawyer participating in the conversation told us some of these hesitations were justified. The laws surrounding reporting and sharing this sort of information is murky and often not on the side of innovative solutions.

The proposed accountability system with the most buy-in, which kept cropping up during our discussions, was also the one that would be the largest undertaking: an external organization to receive reports and address harm across companies. This external organization would act as a central HR department to communicate incidents of misconduct in line with laws and union regulations, and to aid in the meaningful address of these reports. Such an organization could:

- Be available to all New England performing arts organizations as a co-op-style employee-relations group, allowing smaller organizations to access resources they could not otherwise afford

- Be a place to register complaints and act as an information clearinghouse and historic database; reports would be available to all theatres in the community, not just the one where the incident occurred, which would offer a higher degree of trustworthiness than just word of mouth during hiring and casting

- Have processes in place to allow for meaningful address of misconduct reports, which might include:

- An outside firm to conduct an objective investigation for more severe cases

- Available on-call restorative-justice facilitators

- Harassment consultants

- A system for anonymous reporting

- Facilitate training in intimacy direction, consent, bystander intervention, and inclusivity, and provide certified credentials to artists and organizations who participate in these trainings

An organization like this provides a layer of remove for individuals wishing to report an instance of harassment without fear of being labeled as a troublemaker, not being taken seriously, being intimidated into dropping the report, or receiving whistleblower retribution. A centralized database could also mitigate the number of freelance offenders who just move to a new company if they’ve been reported. It could give artists peace of mind and a manageable path to resolution that feels less perilous and career damaging.

There are models out there we can pull from, such as the US Center for SafeSport, but each has its own flaws and none are built to function with the unusual requirements of the theatre sector. If this entity were to be created, it would be an immense effort, but it’s one many people are standing behind.

The proposed accountability system with the most buy-in, which kept cropping up during our discussions, was also the one that would be the largest undertaking: an external organization to receive reports and address harm across companies.

Next Steps (Ours)

The next step for StageSource is to continue working with IMPACT Boston. This summer, Meg Stone, who works with them, is piloting a bystander training program specifically designed for the needs and situations of a theatrical working environment. With IMPACT’s aid, we are also seeking funding for the exploratory process of creating an external reporting entity.

In April, we brought a series of four “Introduction to Intimacy” workshops to Boston, taught by Claire Warden of Intimacy Directors International. Just shy of one hundred artists were trained in a single weekend on the foundations of intimacy work in theatre. We also noted a shortage of trained intimacy directors in our region, so we are currently in discussion to bring workshop intensives to New England this fall to get local artists on the path to becoming certified intimacy directors.

We also recently formed the Line Drawn Working Group, made up of New England–area artists, technicians, administrators, and board members. This group will continue to convene on a regular basis to share strategies, develop new resources, build community standards, explore an external reporting entity, and continue building momentum for change. If you live in New England, you can join the Line Drawn Working Group to stay up to date on our work and share your experiences and insight.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here