On Dreaming Early, Beach Dramaturgy, and an Old Stinky Mop

An Interview with Heidi Taylor

Elaine Avila: Can you describe Vancouver for our international colleagues?

Heidi Taylor: Playwright Hiro Kanagawa gave a fantastic talk looking at our colonial history, the technological history, and the relationship to futuristic dystopias through William Gibson’s writing. I found it very stimulating and thought provoking. It helped provide the LMDA (Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas) conference theme, “Adapting to Change: Creative Response in the Terminal City.”

This idea of Vancouver as a terminal city is an interesting one. Some take it in a negative sense, "the end," and in some ways it is—the edge of the continent. It's a port, a railway terminus, a hub for immigration, while simultaneously the home of ancient indigenous cultures. We're perched on the edge of a rain forest; you can look at snow-capped mountains while swimming in the ocean, all minutes away from a theatre.

Here the first nations history goes back to time immemorial. The first nations culture here is very current and lively, with a strong impact. We have one of the few urban reserves in the country, the Musqueam Nation in South Vancouver.

You also have this puritan level of colonialism—the no dancing in restaurants by law, no beer on the streets, and an emphasis on the rights of the home owner. Someone might move in right next door to a venue that’s been operating for thirty or forty years and then make noise complaints and put that venue at risk. Even for people living in metro Vancouver, they often approach their cultural activities as suburbanites. The city and the parks board are very forward thinking about these questions. How do we plan communities so that there are artists in every community, each part of our city landscape?

Elaine: What do you wish your colleagues across the United States and Canada knew about west coast playwrights?

Heidi: They are very theatrical; there is an awareness of the audience that comes through in a lot of different styles. At Vancouver’s Playwrights Theatre Centre (PTC), we have a variety of aesthetics, content, concerns, threads.

Sited performance is perhaps one of the most emblematic aspects of Vancouver theatre. You can expect that it is going to be happening in unusual places. That reflects something about Vancouver’s audiences. They’re interested in events. That affects the way theatre is made here. There is a real focus on the social event of theatre.

We need to contract our relationships. We need to talk about how we work best. If you are in a playwrights’ development center, you’ve got to have that conversation with every single writer, for every single project. People change. The project has different demands. The closer you are to a writer, the more you may be susceptible to assumptions that are going to kick you in the ass down the road.

I couldn’t describe everything that’s happening in west coast theatre. There’s a lot of it that I don’t get to see, pockets of the community that I may not know. That is important for all of us Vancouver theatremakers to begin to grapple with: that the community has grown to a size that nobody knows the whole community.

New work now coming out of some of the training institutions is often the response to the real maturation of the devised and image based companies that came out of the late 90s. The new artists are making something different that, in some ways, is more traditional, with a flavor of those experiments that permeates through.

Elaine: What do you wish our colleagues knew about dramaturgs?

Heidi: I wish people knew what to pay them. There are free guidelines available on the LMDA website. Not just the amount of time it takes, which is often completely underestimated, but what kind of expertise is required. A dramaturg must know:

- Whatever is happening in contemporary theatre.

- Whatever subject matter the writer is working with.

- An awareness of what potential lies in a draft.

- To be able to see what lies beyond what’s on the page.

- To see where the fruitful pointers are.

- To not pass judgment too quickly.

Those are all skills that a good dramaturg has to unwrap a little bit more for other theatremakers. Theatre makers who collaborate deeply with dramaturgs obviously honor that process, but it can be hard to quantify as dramaturgs. It is always a value of mine to make sure the primary creator gets paid.

In a context of scarcity, that can mean undervaluing the dramaturg’s contributions or not articulating what those contributions are in as robust a way as we could. It’s about understanding what our role is and sharing a vision for that. How do I as a dramaturg help theatremakers see dramaturgy as an essential part of every theatre process and then make sure that we invest in it?

We need to contract our relationships. We need to talk about how we work best. If you are in a playwrights’ development center, you’ve got to have that conversation with every single writer, for every single project. People change. The project has different demands. The closer you are to a writer, the more you may be susceptible to assumptions that are going to kick you in the ass down the road. Expressing what their needs are is a part of the conversation I find playwrights to be depressingly terrible at…the kinds of contortions they’ll do…

Elaine: How would you describe the theatre community in Vancouver?

Heidi: There’s the potential for something to accelerate through small-scale production to presentation by other companies in a fairly rapid way. Some very recent university grads put their first, all original, project together, STATIONARY: a recession-era musical, by an amazing theatre artist Christine Quintana. It premiered at the Neanderthal Arts Festival, for emerging artists, and then went on to get presented at Presentation House, a major theatre on the north shore of Vancouver.

There is another stream of Vancouver theatre that is very internationally focused, stimulated by the PuSh Festival, an international performing arts festival very similar in terms of its programming to On the Boards in Seattle, and Under the Radar in New York. Executive Director Norman Armour and his curatorial team shop at the same places as those festivals. He cultivates collaborative opportunities between the visiting and local companies. The festival is big enough that there is a range of work coming from all over the world, but it’s small enough that you can meet and talk to those artists and create that sort of genuine connection that results in future collaborations. There is a direct link. Rimini Protokoll, for example, has had a big impact on the aesthetics of Theatre Conspiracy’s productions, and Theatre Replacement has broken into the international touring circuit.

Elaine: What excites you most about your transition from Dramaturg to Artistic and Executive Director at PTC?

Heidi: I am interested in seeing how PTC functions in the dramaturgy of the city. Maybe that’s just a way of me searching for a new building, reading bylaws and things like that. I’m kind of an urban planning nerd, I dig reading about how cities grow and change. Where do playwrights live in our culture? How can we make the support they receive equivalent to the incredible investment that writers put into their work?

Elaine: You mention that one skill a Dramaturg needs to have is finding potential in a script. How do you develop this aspect of your practice? I think that is something we tend to be weakest at (dramaturgs, playwrights, teachers, the field in general).

Heidi: It is really challenging. The best way is to know the artist, to be able to see their work being done. Whether it’s a little workshop in the back of a grocery story or a self produced project or even a video clip, it gives me a sense of what they’re aiming at. What the theatrical blanks are—that are maybe in their imagination, but not on the page yet. There is a sense among some playwrights that “people aren’t getting my work…why isn’t it getting produced?” And I read it, and it’s not getting produced because it’s not very exciting. It’s a competent, old-fashioned play. And I’m just not interested in that. Its not to say there isn’t a market for that. I’m interested in theatre that acknowledges its form. It doesn’t have to be violently experimental. But it needs to some how place itself within the world. You can have a really compelling story, issue, character, that you just want to know more about. If a script makes me feel curious in some way, awed in some way those are usually good signals for me that there is something going on there.

Elaine: What are your views on diversity in terms of PTC programming?

Heidi: I go back to what my mentor, Don Kugler says, “your choices and your actions tell people what your values are.” Keeping that in mind has helped me clarify programming decisions. I need to be clear about every single playwright relationship I take on. If not enough women playwrights apply, I realize I didn’t do my job in clarifying this opportunity to enough women writers and I’ve got to fix that.

When we designed the Associates Program we decided to have a designated position for an aboriginal writer. There are incredible aboriginal writers here, but we looked at the density, and it is not layers deep. Many aboriginal writers go immediately into film. We need to make the potential in theatre clear. Part of it is to focus on what I don’t know. If I don’t know how to support that work, I find out or make a connection to those who can.

Elaine: One of your values as a dramaturg is early witness. In my experience this is unusual. What has emerged from this practice?

Heidi: For me, it’s part of having so many projects on the go simultaneously. What are you reading? What are you researching? Can we read alongside each other? Can I know what I’m looking for with my recreational net surfing? It helps me feel we’re in the same story; we’re on the same investigation. We can make mistakes early on, that can get corrected while the stakes are low.

If I have an interest in a very generally proposed project and start to research that and send links and I don’t get any response, and a writer doesn’t have much of an interest, then it tells me something about her proclivities. It also starts to establish a rapport, so that we can send one line e-mails to each other and have a sense that it’s a conversation that’s already ongoing.

For writers, its nice to know do you write daily or do you need a week where we find you a cabin to go crazy? What’s your time signature? And to acknowledge how those time signatures shift.

That work may be beach dramaturgy—taking the dog for a walk and talking generally about the piece when the writer isn’t ready for me to read anything. I can get a sense of what their emotional relationship is to how they’re writing.

You have a sense of how writers are serving a particular process.

Some of my writers want to go off, finish drafts, and then start to engage. I give writers the option. Send me something every week, we don’t have to talk about it…use me as an internal deadline. Then when you finish the draft and say hey, can we meet tomorrow? I’ll be ready, because I will have been reading along with you and actually be able to say something intelligent. If you haven’t let me read anything for three months and then you give me the script, then, no I can’t meet tomorrow.

Elaine: When you and Kathleen Flaherty (the Dramaturg at the PTC) met with me about my next play, asking about research, it felt like I was opening this wonderful box. Synchronicity starts happening early.

Heidi: Dreaming early allows you to recognize opportunities as they come up and to prioritize taking advantage of those opportunities.

Elaine: I recently read your article with Steven Hill, “Devising Disaster” in Canadian Theatre Review. You practice a kind of non-traditional dramaturgy that can be extremely time intensive. How did you come to be an expert in that area of the field?

Heidi: “I don’t know, how do you do that?” is the basic question that arises for pretty much every project that I do, actually a useful dramaturgical starting point.

My roots go back to my training at the University of Toronto that had a very rigorous approach to dramaturgy. We did new work. The sense of structure arising in the room is something I have explored to the nth degree at Leaky Heaven under Steve Hill’s direction. I regularly ask—”What do we need in the room, what are we going to get out of the room?”

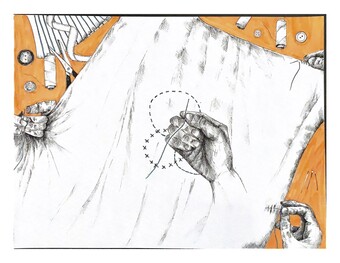

When we did Antigone Undone which Michele Valiquette dramaturged and created the script for, I was the consulting dramaturg, there was a point when there was an image being created in the corner. The actor grabbed an old stinky mop and created this incredible image of Antigone’s brother in a field, stabbed and suspended on a spear. The lighting guy focused on him immediately, ‘Bing!!” Then I thought, ‘”Oh crap. That mop is going to be in the show now.” The massive mop head was the only thing that would stick to the wall appropriately.

That’s something I accept now. Examining everything that’s in the room is part of the dramaturgy.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here