Gilgamesh and Guantanamo

D.C. Theater Explores the Spoils of War

On a recent May night, on two stages in Washington, DC, two separate demigod kings suffered and grew wise. At Constellation Theater, Gilgamesh fluttered the sleeves of his royal raiment and ordered a boy jailed, a toe cut off each day and sent to his father.

Gilgamesh is the tale of a cruel man-god transformed by grief. In verse and the first produced play written by Pultizer Prize-winning poet Yusef Komunyakaa, with dramaturgy by Chad Gracia, Gilgamesh is based on the earliest surviving work of Mesopotamian literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh. The epic poem chronicles the exploits of a king who ruled what became modern-day Iraq some 4,500 years ago.

Komunyakaa and Gracia have carved the epic down to a sumptuous drama. The story is familiar to many hero myths: the hero harrows hell to bring back a boon for humankind. In this case, interestingly, the hero fails.

In this case, interestingly, the hero fails.

Gilgamesh is a tyrant, imprisoning people who are unable to pay him their tribute of meat or wine, entering the bedchambers of virgins on their wedding nights to exact his due. “I am afraid/ the part of you that is god/ has eaten the heart of the man,” his mother worries. Enkidu, a man-beast created by the gods to distract Gilgamesh from oppressing his people, searches Gilgamesh out to tell him he is a bad king. When they cannot defeat each other in a fight, Gilgamesh recognizes Enkidu as the friend he has dreamed about.

Together they go to battle against the evil Humbaba and defeat him. But the price of slaying him is Enkidu’s death. “I struck at evil’s first/and last birth roots,/and we are both innocent,” Gilgamesh says. Enkidu wonders, “Can we be innocent/with blood on our hands?” Apparently not. Enkidu dies of a sudden fever. Gilgamesh, destroyed by grief, descends into the underworld in an effort to bring him back to life.

The life-giving flower he fishes out from the depths of an underworld river is stolen from him while he sleeps. He returns to his city with Enkidu dead on his shoulders. He frees all the prisoners and demands that a feast be prepared. “Teach me to be a king,” he implores. “Teach me to die like a man.”

The strength of Komunyakaa and Gracia’s play is its poetry—which is also, at points, its weakness. The language is steadily lyrical and sound driven, at times sacrificing immediacy and clarity simply to please the ear—a fine enough aim in poetry but one that works against our involvement in the action of the drama.

And sometimes the metaphors are less than fresh. A woman comes to Gilgamesh to beg for her husband’s release from the stockades. “Do you remember these breasts?” she asks him, hoping to use her sexuality as leverage. Gilgamesh answers, “They are still succulent as the ripest fruit.” We expect more from Komunyakaa.

But generally Komunyakaa’s poetry is alive. If it keeps us at a distance, with its slightly formal, elevated diction, it also keeps us carefully attentive. The poetry sharpens when the action intensifies. Both beautiful and hard-hitting, it serves the drama while sending shivers down the spine. Gilgamesh says of Humbaba, the evil one whom he has come to kill,

Humbaba is no god.

He is a small beast

in a big forest.

He is only a roar

among the night trees.

The ferryman who has tried to dissuade Gilgamesh from crossing the underworld’s river waxes eloquent in a direct and powerful way:

I tried to tell him

the night winds are blades

whittling a bone . . .

As Gilgamesh returns to the city with Enkidu’s bones on his back, a chorus member remarks, “He’s carrying grief / in a grass sack.”

The power of the language and the elements of Constellation’s production—gorgeous and surprising costumes, compelling music played by a single musician live in a corner of the stage (drums, keyboard, kalimba, and seventeen other instruments), skillful choreography and mesmerizing dance—are more memorable than the king’s struggles or triumphs. Constellation founder Allison Stockman, who earned a degree in comparative religion at Princeton before studying directing, produces plays that explore universal questions.

Gilgamesh does raise the big questions but is too diffuse in its themes. Mortality and its acceptance, friendship, power, the difference between god, beast, and humankind, the search for a name: all are inquiries or feints, either hinted at and dropped or neatly tied up at the end—too neatly. Nonetheless the play succeeds in making the spine tingle. Afterwards, the audience buzzed with excitement and seemed to have been uplifted, put in touch with the eternal questions, whatever they might have been and however they might have been answered.

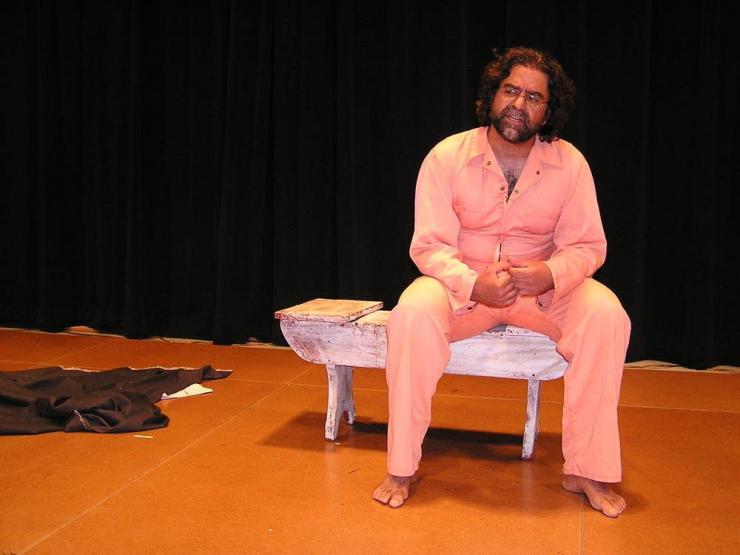

Just up the street from Constellation, at the DC Arts Center, another demigod from ancient times prowled the stage—in this case, Jesus. Matthew Vaky’s one-man show, Jesus at Guantanamo, is every bit as carefully wrought as Gilgamesh—more so, even—and is vitally important.

Like Gilgamesh, it explores power and its abuse, an apt topic for a DC stage. The play is taut, funny, gut-wrenching, and never predictable.

Like Gilgamesh, it explores power and its abuse, an apt topic for a DC stage.

Off-stage, as the play begins, Jesus intones the Sermon on the Mount. When he reaches the line, “Blessed are the pure in spirit: for they shall see God,” he pauses. “TA-DA! Can you see me? You can’t? Well, I guess you aren’t very pure in spirit, then.”

He emerges in an orange jumpsuit, laughing.

“I’m just kidding. Relax. What are you afraid of? It was just a joke. It’s me. Jesus. Christ, not Jimenez. You know, King of kings. Lord of Lords. God. Blessed are the pure in spirit, for you shall see God. Ta-Da. Well, the Son of God.”

He pauses and considers his jumpsuit. “Does this thing make me look fat?”

Alternating between humor and earnestness, with the light ball-of-the-foot dance of a boxer, Vaky leads us gently into places none of us would otherwise willingly go. That Vaky chose Jesus—an innocent man—as his protagonist is in one sense outlandish but in another terribly apt. Of the almost eight hundred men jailed at Guantanamo over the years, only eight have been convicted of any crime. Most were never charged or tried. A 2006 review of over five hundred prisoners found only eight percent had been Al-Qaeda fighters. Many of the detainees, like Vaky’s Jesus, were handed over by individuals interested in claiming the five-thousand-dollar bounty American troops offered for presumed terrorists. Out of desperation, at least a hundred men have embarked on a hunger strike, which is now entering its fourth month.

Vaky launches headfirst into the current crisis at the prison:“ . . . the guards are holding them down, putting a nice long tube down their noses and feeding them a cool refreshing can of ENSURE. Sounds like heaven doesn’t it? Unless you don’t like Ensure. And I don’t think you get to pick your flavor.”

He deftly pivots back again into humor. “Hello, I’m God incarnate, I can hear your thoughts. So I know what you’re thinking. Right now you’re thinking—Well, right now you’re thinking can he really hear my thoughts? But before that you were thinking, ‘He’s not God. He’s some nut who thinks he’s God. This place made him go crazy.’ Don’t deny it. I can hear your thoughts. There’s only one of you out there who thinks I’m really Christ. Thank you, by the way.”

With this perfectly timed, skillfully acted, and adroitly devised approach and retreat, Vaky moves ever closer to the throat.

The play is never tedious, never heavy handed. Vaky understands how each word will work to draw the audience in. A former member of the Guthrie Acting Company in Minneapolis, he has worked for years as an actor, director, and writer.

Only someone with his finely honed talent could take us so deeply in. He passes around a picture of Maher Arar, the Canadian citizen mistaken for a terrorist while in transit at JFK airport. Our government rendered him to Syria and Jordan, where he was brutalized for months. Then he passes around photographs from Abu Ghraib. “I’m sorry,” he exclaims, pacing the stage as nervous, neurotic Jesus. “I’m sorry. Keep passing. Keep passing. Everybody needs to see.”

Tears are flowing down the audience members’ faces. We are experiencing, communally, for the first time, those photos. That is ritual. And that is necessary.

Although it wouldn’t seem possible after that moment, the intensity continues to build. Vaky encapsulates the evolution of human rights law over the past few hundred years.

You decided that you couldn’t hide people away and not give their families a chance to see them. And it was good. You decided that you couldn’t lock people up indefinitely. And it was good. It was all good. But even through all that history of doing good, you stayed so afraid. But what are you really afraid of? Are you afraid of evil? Or are you really afraid of good? Are you afraid of others? Or are you really afraid of yourselves? I’m not going to give you any answers, because I don’t know. I really don’t know. . . . All I know is that you always have the choice to turn the other cheek. And you choose the crucifixion every time.”

At the beginning of the play, he frets, “They’re going to string me up again, aren’t they?” Now it is no longer “they.” He places the responsibility squarely in the hands of the audience.

“So what’s it going to be this time?”

He cues the song, “You Can Leave Your Hat On.” He unzips his jumpsuit, strips down to his boxers, gyrating. He grabs a blanket, holds it in front of himself as if suddenly bashful.

When the lyrics command, “Come back here, stand on that chair, put your hands in the air, shake’ em,” he climbs on a chair, blanket over his head, hands outstretched. And we have before us the iconic image of the man standing on a box, hands held out to the wires.

The play ends with Jesus making a pivotal decision about his fate. Just before making his decision, he asks, “When I was hungry, did you feed me? When I was thirsty did you give me water? When I was sick and in prison, did you come to me? Because verily I say unto you, what you do to the least of these, you do to me.”

Jesus at Guantanamo is a skillful and intensely relevant play. It deserves a long run at a big theater, rather than the three-night, self-produced run it recently had at a theater with sixty seats. It is a play our country needs to see.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here