A Higher Quality of Confusion

How to Make People Disagree

This three-part series chronicles the musings of a twenty-something college grad making theater in London, trying to figure out what to bring home.

My most recent moment of hideously embarrassing American ignorance came while I was in Edinburgh, spending a week at the Fringe and someone asked me what my opinion on Scottish independence was. I assumed that the question was entirely hypothetical, and it had to be explained to me that Scottish independence is a real, pertinent issue currently unfolding in the UK and on the 18th of September, 2014, the Scottish people will vote in a referendum to decide whether or not they want it to happen. It is an example of democracy at its most direct and, as with every important decision, it is a hotly contested issue.

There are several shows on the subject at the Fringe this year and over the course of the week I discovered that all of the people I spent time with, artists who loved and respected each other, had radically different opinions. A director explained to me that to leave Britain would be disastrous for Scotland’s economy while the actress in his one-woman show argued that the independence from empire is to be celebrated, and that to deny that to Scotland would be fundamentally opposite of what the so-called free world values. I cannot pretend that, after seven days in the country, I have a nuanced or even detailed opinion on the question, but the conversations are still ringing in my head.

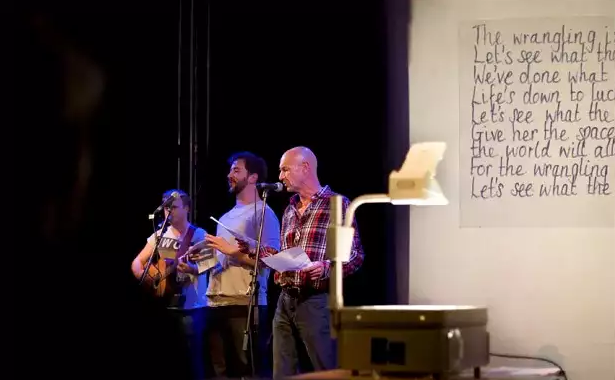

The most salient discussion of the issue, I witnessed in my time in Edinburgh, took the form of a piece of theater, The Bloody Great Border Ballad Project. Staged at Northern Stage at St. Stephens it is described by the theater as “part protest, part prophecy, part poetry, part party.” The night I was present, it was also part sing along, part ghost story and part astrophysics lecture, and afterwards almost the entire theater moved to the bar across the street to talk and drink.

The form is a mash-up of hybrids; first, two of six “resident balladeers” present a short piece, a ballad in the loosest form possible, that touches, somehow on borders. The night I went, I saw an astrophysics lecture about the possibility of life on other planets and was invited onstage with the rest of the audience to help tell a community-facilitated ghost story about social programs cut under the recent Tory budget cuts. At the end of this, the resident balladeers line up on stage to tell a story that was being written over the course of the entire festival, a more traditional “border ballad” about a baby girl found floating in the river between Scotland and England in the years after Scottish independence. In each performance, a new artist added a verse, taking the girl’s story another five years into the future so that the story grew as the Fringe progressed, finishing up at 18 verses in the year 2104.

In his opening speech, the artistic director of Northern stage described his motivations for bringing together the show, primarily his doubts over the situation in Scotland. He talked about the weeks of watching the debate unfold, seeing the differing opinions put forward by his actors and he stressed that the outcome was not a clear one, not a banishing of doubt, but “a higher quality of confusion,” a confusion that was at least informed, at least diverse.

The best description I have ever heard of political theater, and the mantra that I try to stick to is that “political theater excites our ability to disagree.”

The question of what political theatre should do is one that theater-makers, or at least the undergraduates I’ve spent most of my time making theater with, are constantly grappling with. The best description I have ever heard of political theater, and the mantra that I try to stick to is that “political theater excites our ability to disagree.” That sense of creating a space where audiences can disagree has always seemed to me to be one of the great challenges in America, where theaters tend to be patronized by very specific set of cultural groups. I have seen a lot of writing recently on HowlRound about theater relating to gun control, and every time I wonder whether those shows achieve that spirit of debate. The amazing thing about Border Ballad Project was that it was, to borrow a very American descriptor, truly bipartisan. Not all of the performers agreed, not all of the audience agreed. I can’t say that I know for a fact that anyone walked out of the theater with their mind changed, but I can say that there were challenges to every opinion and that no viewpoint was entirely validated or entirely vilified. I believe staunchly that America needs tighter gun control laws, and I believe that theater can be used to approach politics, but nothing is more frustrating than sitting through a political piece where you can feel the entire audience around you agreeing, where you yourself are agreeing because you aren’t being challenged by your theater, and if you’re not being challenged, is it really theater, or is it just cultural validation?

If you find yourself interested in seeing parts of the Bloody Great Border Ballad Project in action, the ballad written over the course of the festival is available on YouTube and the lyrics can be downloaded from Northern Stage’s website. Both the videos and the lyrics can be found in the show link above.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The proverbial Devil's Advocate: if a piece only introduces a Babel of equal morally/ethically/spiritually "valid" viewpoints, what's the difference between the show and turning on the cacophonous din of primetime cable news?

Theatre challenging the accepted status quo > Theatre strongly concurring with community's expected beliefs > Theatre with a variety of equally "valid" opinions. The second at least stakes a strong claim, e.g. "Laramie," which has an obvious and almost universally accepted editorial stance within a sea of opinion.

Some absolutely incredible food for thought in this piece, thank you so much for writing it. I want to say more, but it's going to take a bit for me to digest the questions you've raised. Thank you for raising them!