How Post-Colonial Imagination Can Make Theatre into an Agent of Revolution

Playwrights have particular access to the revolutionary potential of theatre by the choice of political roles they take on. In the act of political and artistic subversion, playwrights assume the mantle of truth-teller, historian, sociologist, and documentarian to help combat oppressive cultural and political dynamics.

One way revolutionary theatre takes form is in anticolonial work, in which artists examine implicit power dynamics within colonial states and imperialist movements, and deconstruct them aesthetically, historically, and symbolically. Such work is dependent largely on the playwright’s ability to access a deep anticolonial imagination—one that manifests the contradictions of statehood and national identity onstage—and project a narrative in which both can be subverted. This kind of theatre isolates oppressive colonial dynamics and provides cultural narratives and references from dominated cultures, wrenching them from the historical erasure they have previously been subject to.

Subversion is an important function of theatre and one that the art form, in its potential for rewriting history and confronting colonial logic and dangerous racial and cultural hierarchies, is uniquely suited for. Playwrights write about the tensions between the dominators and the dominated—skewering oppressive cultural narratives, uplifting and reinvesting in the work of the oppressed, and providing a potential future for liberation. The playwright is an intermediary between cultures, a documentarian of the multiple rifts and collisions between nations and peoples. Theatre becomes a medium in which an anticolonial archive can be accessed, cultivated, and deployed, and where an anticolonial future can be constructed and imagined.

Deconstructing the Colonial Gaze

David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, a study in the gendered politics of Western/Eastern domination of China, provides a particularly powerful rendering of the white colonial gaze. The play follows the true story of Rene Gallimard, a French ambassador to China during the Vietnam War, and his relationship with a performer in the Chinese opera. For the first two thirds of the play, the narrative is controlled and navigated largely from the perspective of Gallimard, giving an account of his heavily Europeanized tales in the “exotic East.” It is made clear by his erotic projections onto his surroundings that his lover, first introduced as Song, is not simply a beautiful woman to him; she represents a fetishized archetype that has long been the object of his obsession. As their relationship unfurls, Song becomes not just the manifestation of Gallimard’s white male desires, but a conduit to a culture and life that he has admired from afar but never approached.

Halfway through Act II, however, the narrative implodes on itself as Song is revealed to be not only a spy for the Chinese government using Gallimard for his intel, but also a man dressed as a woman. The reveal is shocking and damning; Gallimard’s active fantasy life is suddenly collapsed, and the motivating factor behind his delusions are picked apart in a dramatic courtroom scene in which Song, now dressed as a man, testifies against Gallimard. In describing their relationship, Song touches on an archetypal “rape fantasy” that European men harbor toward both Asian women and Asian culture in general, stating that “her mouth says no, but her eyes say yes.”

Elaborating on this dynamic, Song expands to the Western man’s perspective in general, stating that “The West thinks of itself as masculine—big guns, big industry, big money—so the East is feminine—weak, delicate, poor... but good at art, and full of inscrutable wisdom—the feminine mystique.” Finally, when asked about whether or not Gallimard suspected Song’s maleness, he answers: “You know? I never asked.” Thus the narrative turns on its head; the delusions of Gallimard are revealed as the delusions of the audience, who has accepted the perspective of the Western white man and are implicated in the violence of his gaze.

Hwang’s use of the anticolonial imagination is particularly deft in his detailing of the gendered dynamic of East and West. He takes the traditional Western gaze as interpreted through the play’s most cited piece of media, the opera Madama Butterfly, and deconstructs it through the fallacies of its Western protagonist. Hwang thus parodies the perspective of the Western state and reveals the conviction at the center of its relationship with the East as nothing but illusion. Such confrontation of colonial logic is vital to the anticolonial work of theatre and provides us with a precedent for the deconstruction of the colonial gaze.

One way revolutionary theatre takes form is in anticolonial work, in which artists examine implicit power dynamics within colonial states and imperialist movements, and deconstruct them aesthetically, historically, and symbolically.

Playing State

In Iphigenia Crash Land Falls on the Neon Shell That Was Once Her Heart, Caridad Svich’s swirling dark poetry reveals the oppressive and highly gendered nature of state surveillance and warfare through purposeful fragmentation of Iphigenia at Aulis, a classical Greek tragedy that in part forms the bulwark of the theatre canon.

Those familiar with the original tragedy will find its most basic plot structure intact; the great general Agammemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia for political gain: to ensure victory in the upcoming Trojan War. Svich’s incarnation rips through the play chaotically, setting the conflict within a violence-torn Latin American country and recasting Agammemnon as Adolfo, the unpopular martial leader of a divided state struggling to control his public image. In a desperate attempt to win the loyalty of his people and bring his nation to quick and efficient war, he hires a hit on his own daughter to make a martyr out of both himself and his family.

Pushed to escape from the heavy surveillance under which she is placed and the impending doom of her father’s choice, Iphigenia runs to the warehouses at the border of the nation in search of the certain nihilistic hedonism of clubs and parties. Back at home, her mother laments her position as Adolfo’s trophy and expresses an incredible apathy to Iphigenia’s danger. As Iphigenia throws herself into the mind-bending excess of raves and affairs, she is watched over and commented on by the ghosts of fresa girls who were murdered in the maquilas, factories often placed on the border of Latin American countries that are reliant largely on the cheap labor of poor women. Iphigenia awaits her looming demise at the hands of her father’s assassin, aware of her surveillance by the state and eagerly anticipating freedom from her father’s tyranny.

This fusion of past and present—a classical Greek play represented in a contemporary Latin American setting—welds together two cultural contexts to illuminate a historical precedent to the politics of femicide; we are presented with the classical archetype of the woman sacrificed for the sake of national unity. Adolfo’s choice is thus not shown with attention to his roiling inner turmoil, but to his calculating political mind. He is not simply a man of authority with a conflicting choice to make, he is in fact one of many men in a long line who are willing to exploit the deaths of women in order to generate national sympathy and invigorate a masculine desire for vengeance. The gendering of war and sacrifice are displayed in this dynamic, as Iphigenia’s murder as well as the deaths of the fresa girls of the border and even her mother’s domestic entrapment are thrown up as facets of national identity. Svich’s interpretation of Iphigenia at Aulis leads us to understand that the problematic dynamics present within classical Greek culture—namely the use of the female body as the site of military propaganda, the utility of femicide in the formation of national identity, and the use of women as powerful political currency—are not simply the archaic particulars of a lost culture. This gendered domination was vital to the construction of the contemporary nation-state and recontextualizes the problems of Greek colonial oppression to contemporary Latin American politics.

At times, the heavy state surveillance of these women is literalized, depicting them through the refraction of security cameras. In other instances, the gaze switches to those of the women—narrated by Iphigenia, the fresa girls, and Iphigenia’s mother—who make the violence of the politics that governed Iphigenia’s marriage to her husband incredibly clear. The nationalistic frenzy that accompanies the murder of beautiful young girls is deconstructed, parodied, and subverted through context. Svich reinvests the archetypal pretty female victim with feelings and emotional depth beyond dutiful servility and analyzes the massive public indifference to the ritual violence against them. The play looks at the intricate exchanges of power that occur in relationships between men and women, which are often generated by collective national anxiety. Svich here makes a strong connection between classical Western power dynamics and the material practices of colonial forces that hold them as heritage.

This is the crux of anticolonial theatre: the isolation of historical modes of domination and the subversion of such power dynamics. In the inversion of the classical gendered dynamic of father/state and daughter/subject, Svich imbues Iphigenia with a brooding nihilism, her mother with a wounded ferocity, and the fresa girls with a frantic energy that undercuts the trope of the tragic female heroine who is sacrificed for the sake of the male conquest. Here, the bodies of women are divested from their status as national currency and instead given a humanity that immediately rebukes colonial fetishism and implicates the audience in the romanticization of their deaths. Svich offers one of the most vital aspects of the post-colonial imagination in theatre: the gift of voice to the silenced and the reversal of dehumanization in colonial dynamics.

This is the crux of anticolonial theatre: the isolation of historical modes of domination and the subversion of such power dynamics.

Speaking Truth to Power

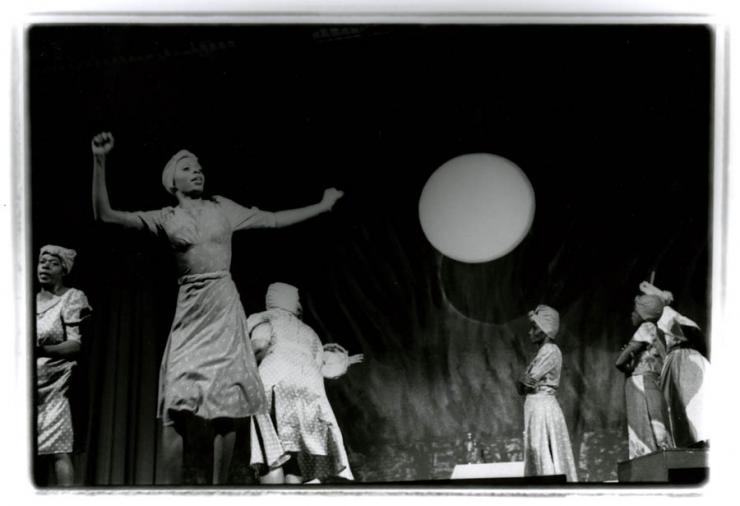

Language is the primary revolutionary element of Sistren Theatre Collective play QPH. The collective, based in Jamaica, works heavily with regional storytelling and testimony, writing plays informed by and crafted for the community. This hyper-localization necessitates a transliteration of dialects and intercultural references that directly contradict received English pronunciation and syntactical structure. QPH itself subverts classical modes of theatrical expression by rejecting the traditional mis-en-scène of Western theatre and instead opting for an experience more akin to rituals, invoking dance and song in grand gestures that totally undermine classical dramatic structure. Indeed, it seems that while the play takes a close look at histories of colonial dominance and offers ample critique, its primary concern is not with explicit analysis of classical Western conventions and philosophy. Instead, QPH reveals the ways in which the women it depicts subvert and participate in colonial structures every day.

The play follows the disenfranchisement of three Jamaican women leading up to the fire at the Kingston Alms house in 1980, a historical event that is well recognized by Jamaicans and the residents of Kingston but not by the world at large. Each woman’s story was extrapolated and synthesized from interviews and testimonies, leading to three distinct storylines: that of Queenie, former lover to a pastor who was thrown from her own church for attempting to take on more authority than was appropriate for a woman; Pearlie, a light-skinned socialite who lost her status and her wealth by her mother when she became pregnant with her gardener’s baby; and Hopie, a former maid disowned by her wealthy employers after the death of their matron. Each woman’s disenfranchisement is displayed in the terms of their social positions; their subjugation is explored through the different ways in which they individually navigate poverty and homelessness right up until the catastrophic ending, in which Hopie helplessly watches as Pearlie and Queenie are burned alive.

None of the depicted women’s stories are privileged over another’s; in fact, they are all told with equal time during a theatrical interpretation of an Etu dance, a ritual reserved specifically for communion with the dead. It is with this framework that the audience is brought from their seats, through the fourth wall, and into the story; we are witness, along with the actors, to the lives of these woman and the events leading up to the tragedy that befalls them. This entirely subverts the traditional theatrical logic by which playwrights and performers provide information for the audience to receive—instead, it invites audiences into an active role. The anticolonial content of QPH is not simply in argument, but by the literal structure of the narrative itself.

At the center of the piece’s anticolonial sentiment, however, is the linguistic intricacy represented onstage. Jamaican Patois is utilized and transliterated in such faithful and complicated ways that the only audiences sure to understand it entirely are those who are fluent in the dialect’s particulars. A scale of fluency is shown in the characters themselves: Pearlie’s pronunciation of English morphs based on the class of woman to whom she is speaking, and Queenie’s pronunciation is much more “proper” when she reads from the Bible. But the meat of the drama—the scenes in which the narrative truly comes alive—are rendered in full Patois.

To an outsider, this choice in language might seem insular or exclusive; what I read was a radical decentering of the Western audience’s comprehension. This play was written for the people it represents and feels no obligation to alter its speech for the literacy of others—a marked departure from the philosophy that theatre must provide a universal human experience. Radicality in this case is not a direct critique of Western domination (though there are racial dynamics present in the plot that point to the colonial history of Jamaica itself), but instead as the lack of attention paid to Western perspectives in general. Whereas M. Butterfly and Iphigenia perform their anticolonial work through deconstruction of the colonial perspective, this play operates as though the colonial perspective doesn’t even exist, offering the community it represents with a voice that it would otherwise be deprived of in Western media.

Conjuring from the Anticolonial Imagination

Each of these plays access the anticolonial imagination in a different way and offer us a view into the revolutionary potential of theatre. Theatre artists possess the capability to reconcile their colonial pasts, subvert violent imperialist dynamics, and, most importantly, imagine a future in which such dynamics can be defeated. In a playwright’s attempts to navigate the complex and interconnected histories of colonial violence, they have the power to shape and project the revolutionary futures that the understanding of these histories inspire.

Illustration by Rey Sagcal, inspired by the essay.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here