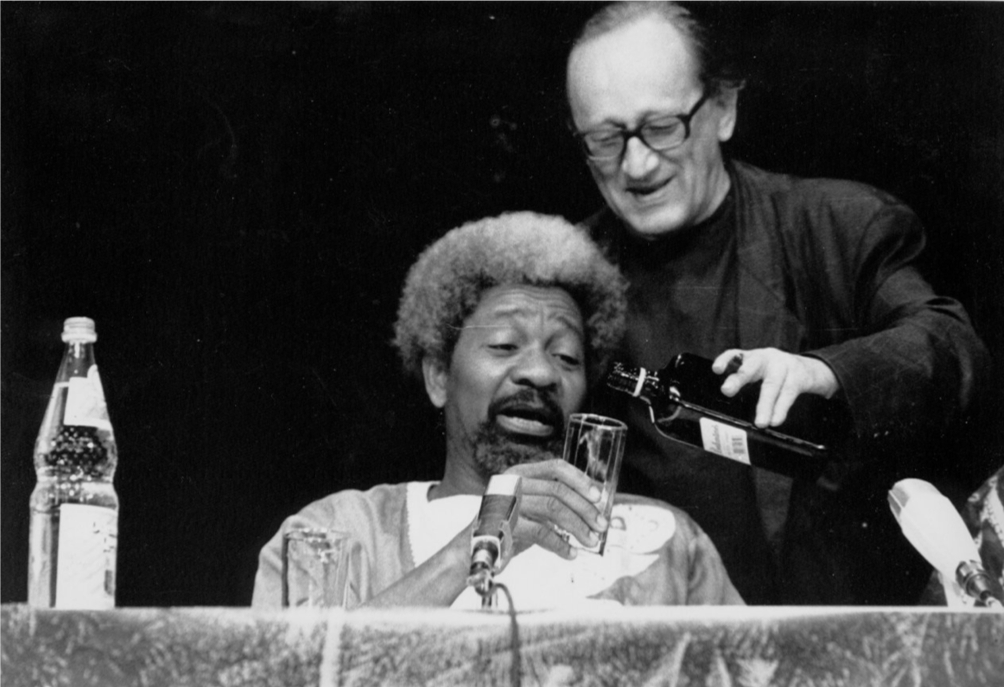

The discovery of the photo was both vivid and vague. It happened years ago as I was scrolling online. The photo is of Heiner Müller, an East-German playwright—the intellectual and spiritual heir of Brechtian thought—pouring whisky for Wole Soyinka, a Yoruba playwright born in Nigeria and the first African to win a Nobel Prize for literature. I don’t know much of the context for it but the photo spoke to me as though this thirty-year-old moment had been staged for my benefit: the “Black” playwright and the German aesthete occupying the same space. This gem encompassed my race, my profession, and my perceptions of the gap between the edgy German artist and the Nigerian Nobel Prize winner.

Last summer, thanks to a grant from Theatre Ontario in theatre curation training, I had the unique opportunity to document and participate in the Stratford Festival Lab’s “Beyond the Western Canon” series. These works workshops had the aim of gesturing toward a decolonial future. There were seven units, each dedicated to a culture historically underrepresented in our theatres. I was pleasantly surprised to find out that one of the units, curated by Ben-Eben Kwabena Tawiah Mfoafo-M’Carthy, would be dedicated to the works of Soyinka—in particular Death and the King’s Horseman, considered Soyinka’s masterpiece, and Madmen and Specialists.

To delve into Madmen and Specialists, a play that doesn’t engage at all with the white gaze, was akin to discovering a new world. Soyinka is seldom produced in Canada, a shocking fact considering the sophistication and depth of his work. His absence from our stages is almost unexplainable, except perhaps that Black theatre produced in Canada usually emphasizes immigrant stories and African American realism. Soyinka’s work takes us to the Continent, a place where North American mainstream culture rarely ventures—with the recent and notable exception of Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther. The representation of Black people in their indigenous territory confers agency, narratives, and aspirations outside of white experience. But casting a light where our society dares not look is surely part of the artists’ mandate, and artists cannot be absolved for keeping rank with collective, willful ignorance. Soyinka is by no means inaccessible, and the most disheartening part of a life in theatre is realizing how the gatekeepers are, for the most part, aligned with political and economic neoliberal power.

To delve into Madmen and Specialists, a play that doesn’t engage at all with the white gaze, was akin to discovering a new world.

In Canada, culture, race, gender, and trauma are some of the pillars of our theatre’s ordained categories. But what if a performance text and its writer don’t fit any of the categories? If “the African,” a Nobel Prize winner, does not appear on our stages, what’s the fate of the multiracial creator who doesn’t even have an immigrant story—never mind an African one—to tell? How does one brand the Black creator who is not African, not an African American, not an immigrant? Take my situation. I’m a Québecer of French, Irish, and African descent who knows nothing of my Black ancestry, and whose white family has been here since the 1600s. What is the point of me if white theatres can’t market me in a predetermined category of brown artists?

I favor a theatre of ideas, a theatre that isn’t rooted in storytelling and characterization. I make no apology for it and will continue working toward and advocating for a theatre by brown people that is formalistically adventurous. North American theatre is a largely populist form, which is part of the problem when it comes to what is put on our stages. But we can learn a thing or two from another medium, which involves audiences in a different way: visual arts. The chasm in the level of discourse between theatre and visual arts here could not be greater. For example, the phenomenal and far-reaching success of Hamilton is entirely different from the success of an Ai Weiwei show. Visual arts have managed to strike a deal with the audience that advantages them both. Art fanciers do not expect to have a perfect understanding of every aspect of every piece, which leaves room for open conversations between the audience and the art. Contemporary art is not afraid to baffle, shock, and make all kinds of demands on the viewer. I believe this should be the same with the theatre we are seeing.

As a child, in my native Quebec, school trips would take us to see theatre most North Americans would call avant-garde and which for us was... just theatre. I couldn’t grasp all of what Carbone 14’s production of Heiner Müller’s Die Hamletmaschine was throwing at me, same with Robert Lepage and Edouard Lock, and yet these interrogative productions left me fuller and fuller for longer than productions that spoon fed me a narrative grounded in unambiguity.

In English-speaking theatre in Canada, I detect a fear of leaving the audience disempowered, and this sense of caution is consistent with other forms where story is everything. As long as we are focused on theatre as story, the visual and mysterious takes a back seat. This vision excludes worlds of possibilities for theatre: theatre based on ideas, conceptual theatre, but also theatre from cultures that are not readily conversant with us. If a spectator without knowledge of Nigerian history or Yoruba culture expects context to be provided by Madmen and Specialists, they would be disappointed. Theatres can provide tools and give the audience member who feels stranded one of those luscious, curated programs that include articles providing historical and aesthetic context. They go for a nominal sum in Berlin theatres, and I’ve seen patrons study them religiously before a show.

James Joyce once said that the only thing he demands of his readers is that they dedicate their lives to his work. Without sinking into self-indulgence and self-aggrandizement, maybe it’s okay to expect that those who come to the theatre keep themselves abreast of world affairs and are aware of major world events, such as the Biafran War in the 1960s. And if they don’t know about it, they can read the program. Every brown person who interacts with the white world is expected to have PhD-level knowledge and understanding of what makes whiteness tick; it may be reasonable to expect a bit of effort in return. Yet even then, an erudite audience is not enough. The audience should be willing to be challenged and find wonder in inconclusive experience. The goal here is to heighten the exchange between artists and the public without fear that the latter will walk away with more questions than answers. The public is not equipped to set the standards of what a fully realized theatrical experience could be. We must bravely present them with these challenges.

But what if marginalized artists decide to make use of formalistic radicalism as a way of reflecting the alienation of being marginalized?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

So appreciated. i recall being advised by a racialized theatre maker in Toronto, a multilingual immigrant from outside North America, that once i moved to Montreal i needed to attend Francophone theatre events, even without knowing French, because i'd gain more as a theatre maker from them than from the English work offered. i've gained also from uses of surrealism, absurdism and other inventive structures in theatre work from South America and elsewhere.

Also recalling a few African immigrant writers and publishers i met once (before social media and digital publishing fully took off) while they tabled at an Oakland, California arts fair by people of color. As a white visitor seeking to ally, i noticed the rarity of scenarios where i'd meet these writers and arts promoters on their own terms; even though they were part of a racially mixed community contributing culture in the city, i wasn't finding where i could be introduced to their work directly, except at a few Black-led vendor spaces. This essay is a provocative reminder of the range of work-making and sharing we must strive for!