Leah Nanako Winkler, The Mikado, and This American Moment

In response to the protest and aftermath of the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players’ now canceled production of The Mikado, this series addresses the racist performance and casting practices of Yellowface in the American Theatre. This series was curated by Jacqueline E. Lawton for HowlRound.

Victor Maog: What happened around the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players' (NYGASP) Mikado? Why did it matter to you?

Leah Nanako Winkler: Here's what happened from my perspective:

I receive a flyer for NYGASP's upcoming production of The Mikado. It looks like this, I post a picture of that flyer on Facebook to make sure that I'm not alone in my visceral reaction. I quickly realize I'm definitely not alone and make the decision to call NYGASP directly. I make three phone calls to NYGASP, described in my post here, and contemplate if I should just forget about it due to fear of hate-mail, threats, backlash, and labeling.

Then I dishearteningly remember the national headlines that surrounded the protests of a mostly Caucasian production of The Mikado done by Seattle Gilbert and Sullivan Society just over a year ago and upon further research, realize this particular incarnation by NYGASP has already garnered criticisms and protests dating back to 2013, which makes me think that letting this production go up without at least demanding a conversation would be irresponsible not only as a artist and an Asian American person, but as a person in general.

I email a few journalists who covered the Seattle protests for advice. Sharon Chen (former editor of the Seattle Times) responds almost immediately, and encourages me to write a post outlining my experience. I’m not sure I would have written one if it wasn’t for her.

I also email my friend Ming Peiffer, who emails her mentor David Henry Hwang for advice, who in turn emails a few other people, who email other people, and pretty soon there is a thread of ten or so activists and/or leaders of the Asian American Arts community that keeps growing and growing. Among them is Howard Sherman of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and playwright Jacqueline Lawton, who begins facilitating conversations that are the first steps of organizing a forum.

Meanwhile, the post that I quickly wrote gets shared and posted like rapid-fire and reaches twenty thousand views in two days. As a result, NYGASP gets bombarded with letters, tweets, emails, and even negative ratings on their Yelp and Facebook pages. Overnight, NYGASP releases a statement on their website explaining their intentions of the production—refuting racism by sighting satire and good intentions and receives further backlash from the Asian American arts community and beyond.

In the next twenty-four hours, our team works around the clock to solidify next steps. However, before we do or say anything, NYGASP replaces The Mikado with Pirates of Penzance at the Skirball and releases this statement. This postponement makes national coverage and prompts even more debates and conversations.

A couple of days later, Playwright Rehana Mirza, Jacqueline Lawton, Howard Sherman, Ming Feiffer, and myself have a civil conference chat with NYGASP's executive director, David Wannen, who describes further developments regarding two previously booked tours of NYGASP's Mikado being replaced with Pirates of Penzance, and another tour that removes wigs, make-up, stereotypical gestures, mannerisms, characterizations, offensive promotional material, and some text, in addition to a program insert for the audience that describes the shift. He then expresses his excitement to break new ground and re-imagine a new Mikado in NYGASP's 2016-2017 season. We end the chat and all of us agree to further discussion at a forum currently being scheduled and figured out. That's where we stand now.

I think Gilbert and Sullivan would have wanted to stay relevant. If they were around now I'd imagine them getting drinks as they brainstorm how or if it's possible to reimagine The Mikado in present day without demeaning a vast majority of a minority group.

Victor: How did you come to your understanding and knowledge around yellowface?

Leah: Disclaimer: I'm half White and half Japanese. I am both races and I am neither race and I can claim what I want when convenient. That is a privilege. Also, outwardly to many people, I'm a white girl, which is also a privilege. So keep in mind I don't speak for all Asians.

I came to my understanding and knowledge around yellowface in 2005. The college I was attending at the time decided to do a production of Carol Churchill's Top Girls and a perfectly kind and beautiful white girl with blonde hair was cast as Lady Nijo, a Japanese character. Being the only person of Asian decent in the theatre department, and also bilingual, I was asked to teach this girl an authentic Japanese accent and help her with the pronunciation of some Japanese words. I did it, because I didn't want to come off as someone who wasn't a team player. But on opening night, as I saw this well-meaning actress shuffling her feet in a Kimono while speaking in this accent I had taught her based off of my mother's speech patterns in front of a crowd of mostly white people who were laughing at her stereotypically Asian mannerisms, I felt deep shame. And that’s when I understood that when a white person dresses up as another ethnicity and uses stereotypes to portray that ethnicity for cheap laughs, no matter the intention, it perpetuates the dehumanization of non-whites that so many people fought against for so many years, and even though I am a team-player and I love jokes, I don’t ever want to be part of one that sets us back to a time where the POC perspective or stories literally didn’t matter unless it could be played for ridicule, especially if it is constructed by a white person who has never experienced this sort of ridicule. That is not only offensive, but dishonest.

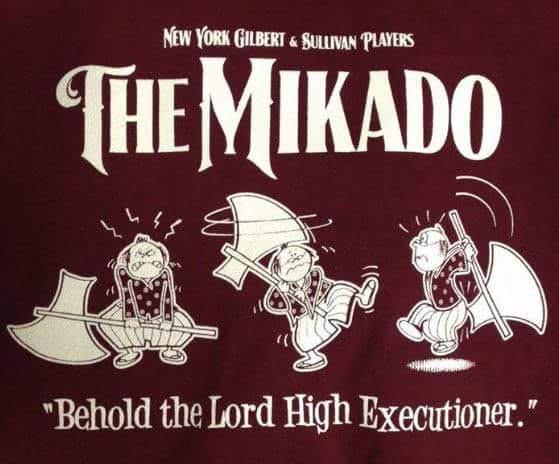

A t-shirt NYGASP sold for a previous production of The Mikado.

Victor: What has surprised you most about this situation?

Leah: I'm surprised that NYGASP was so responsive, but also not surprised considering the many other complaints they've had regarding their specific production of The Mikado over the years as well as the various controversies surrounding The Mikado in general.

I can't say I'm surprised that the Asian American community stood up for themselves, but I am surprised at the relentlessness. For every troll or yellowface defender in the comments section, there are a handful of people who refute their comments. People just aren't giving in. The community has also begun moving the conversation forward themselves in the aftermath of NYGASP’s cancellation by questioning, engaging, and writing. It’s really amazing. I’ve also made a ton of new friends!

Victor: What has surprised you the most about yourself during this situation?

Leah: Although I have the privilege of coming from two cultures, I have personally experienced discrimination and isolation from both sides. Many Japanese people in Japan don't consider me Japanese—I'm considered Hafu, which means half-breed, and one of my earliest memories is being called a gaijin at my own local playground, which literally means foreigner. And white people have always made me the butt of Asian jokes when convenient—my nickname in high school was “crackerjap,” for example.

I used to play along with all this annoying shit with a smile and even perhaps at times I was complicit—using placation as a means for making friends and seeming nice and cool—but as I got older I realized that I couldn't do it anymore. It was too exhausting. So I didn't. And I'm surprised by the strength I’ve found in this exhaustion.

I already know I am cool and nice so I don't have to prove that. And I like being in a world where a woman can be cool and nice and mean and opinionated and classy and classless and compassionate all at the same time and also have a career and be loved and not be just dismissed as some whiney bitch. And what surprises me about myself despite my mistakes, despite my impetuousness, is how my voice both as a person and a writer gets stronger every day.

Victor: Where are people of color having opportunities and where are people of color being held up?

Leah: Right now in storytelling "white" still means "normal" and that mentality can be very isolating for a lot of audiences, creators, and people of color. The audiences have changed but a lot of the content has not. I still rarely go see a play I can relate to (though for me that has to do more with class) but when I do, it's awesome and validating and incomparably rejuvenating. Doesn’t everyone deserve that experience? If so, then why is seeing a cast that isn't an all-white and written by a white playwright who comes from a background of privilege still rare? It's also rare to see a minority character who isn't defined by solely by their ethnicity. And the worst part is, some people just don't even notice these things. It's exhausting and discouraging. And when you point it out, you're seen to be some kind of “fun killer.”

However, I do think the landscape is changing. We have Hamilton, where actors of color tell the story of our white founding fathers in an explosive way (and no, I don't believe white-face is a thing). We have Robert O'Hara who continues to amaze me. Of course David Henry Hwang. The incomparable Young Jean Lee. Tom Bradshaw. Mike Lew, A Rey Pamatmat, Nick Mwaluko, Rehana Lew Mirza, Susan Soon Hee Stanton, Charly Evon Simpson, Jackie Sibblies Drury, Lauren Yee, Nandita Shenoy, Martyna Majok, Jaclyn Backhaus, and many others who write unceasingly for a wider audience.

We also have a handful of wonderful non-POC writers casting actors of color in leading roles that are not defined by race but are defined by complicated, intricate human qualities. I saw it in Max Posner's Judy. Same with Heidi Schreck's Grand Concourse. Mallery Avidon’s “Mary Kate Olsen is in Love.”

There are also great examples of fully-formed characters of color on TV—I think theatre needs to catch up to stay relevant. I think Gilbert and Sullivan would have wanted to stay relevant. If they were around now I'd imagine them getting drinks as they brainstorm how or if it's possible to reimagine The Mikado in present day without demeaning a vast majority of a minority group. They’d probably laugh at the whole situation.

Victor: What's wrong with the system that's not letting people of color through to the top?

Leah: We all love to see own perspectives reflected back to us. But if you're a person of color with a perspective that a lot of gatekeepers (who tend to have the white male perspective) don't particularly see themselves in, then you need to not only be undeniably talented but extraordinary in order to have even a chance. However, if you have a perspective that is considered universal because you have an experience that is common to the people in power, it's not as hard because someone will automatically see themselves in your work. This isn't the only systematic bias, but it's a huge one.

Victor: In your own work, how are you addressing expectations around leadership and diversity?

Leah: No matter the level of the production, I make sure my collaborators know that I don't work with an all-white cast unless it's a necessary artistic device (like Young Jean Lee's Straight White Men, for example) or if I'm participating in a program or exercise where I'm literally drawing actors out of a hat and have no control over the situation. This challenges the casting people to consider actors they normally might not and challenges me to do better artistically.

If I'm writing for someone other than my own race (which is Asian AND white) I ask a friend of that race to read it and buy them a dinner in exchange for an honest reaction (I make sure it’s a friend though—I don’t want anyone to think I’m using them as a resource). If they're offended, I ask why and listen instead of going immediately on the defense. This has made my work more honest and at times, funnier. I advocate for actors who need advocates. I write the perspective that I want to see and hear. I strive to be extraordinary.

Further reading: the Asian American Theatre Series (curated in 2014 by Jane Jung and myself) that laid out the history of the movement, challenges of yellowface, and how Asian Americans create a sense of home despite being treated as the perpetual foreigner. I even confess my own naiveté around the 1990 controversy of Miss Saigon, where British Caucasian Jonathan Pryce played a Eurasian. Some months later, I wrote about the complications of leadership as a person of color and the need to capture our culture. As a theatre community, we seem to be coming to some understanding about the complexity of this American moment and the challenges ahead.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Although I do agree with much of this argument, The Mikado was a satire on the British Government, set in Japan to avoid scrutiny. I am not sure that t believe the show should only be done with a Japanese cast. If this is the cast.

While most of this is spot on, the bit about the author being the impetus for "the casting people" considering other actors they would not normally consider is a bit overreaching; having worked in professional theatrical casting, it is a top priority to find firstly the person who is best equipped to play the intricacies of the role and secondly to find the actor that fits what the artistic team (director, playwright, music director) has envisioned for the role. Casting's job is not to decide who gets the role but to facilitate bringing in the people who are best suited for the project's needs. To assert that any casting director would not bring in people of diversity unless the director TOLD them to is absurd and incorrect.

That's not what I said at all actually...nor is it my assumption about casting people.And why are you assuming I've never worked with a professional casting director?

I appreciate the Top Girls anecdote. So often people can go into a project with complete sincerity and good will and not completely understand the dynamics until it is executed. It often seems there is a swift rush to judgment that can blindside and overwhelm you before you have an opportunity to process and reflect yourself.

I am not necessarily saying this is what happened with NYGASP. The controversy attached to Mikado isn't new. I was at the Arts Midwest Conference this year and NYGASP had a sign and cards with images I feel were a little more exaggerated than the one you link to. I immediately thought of the situation in Seattle.

I was a little surprised when the issue arose just a couple days after I returned from the conference. I guess they started their PR push around the same time.

Even though there was some initial defensiveness when Leah first approached them, I think they ultimately took the right steps to evaluate and address the complaints people were making about their programming decisions.

The thing that needs to be remembered is that the speed at which people can meet and have a measured, deliberative discussion about the problem and how to resolve it is far outstripped by the speed at which social media discussions can circulate and gather steam.

There were three days between the time Howard Sherman posted about it and NYGASP decided to cancel/postpone. From the sense of immediacy about needing to address the issue being communicated by all the conversation about it, I would have sworn it was at least twice as long.