The Lessons of History

Some Post-Election Thoughts

Something profound happened on the first Tuesday in November, something I’m still trying to digest fully. To my mind the election results represent a victory of love over hate, of human dignity over market forces, of public service over private gain. Those who spewed hate toward women weren’t reelected. Those who insisted on heteronormativity as the only way were defeated handily, and those who spouted the rights of the wealthy to buy elections for the sake of perpetuating the private markets of their personal fortunes were sent packing. On that Tuesday, at least for a moment, we redefined public service as something meant to benefit everyone, not just the few.

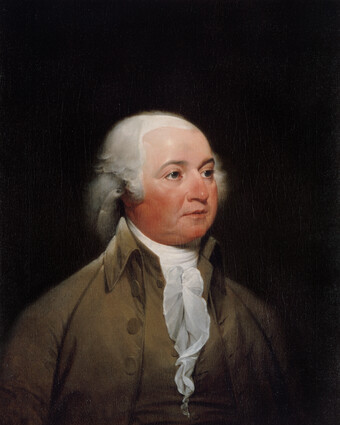

When I moved to Boston several months ago, I decided to watch the HBO miniseries John Adams. I was now living in one of the oldest cities in the United States, the site of the start of the American Revolution, and John Adams lived and worked in Boston and also had a farm in Braintree, Massachusetts, a few miles from my new home. I watched with the hope of gaining insight into my new neighbors and into the new place I was now calling home. HBO doesn’t airbrush history. I didn’t think it was possible for Laura Linney to look unattractive, but everyone in John Adams has bad teeth, not just George Washington. Paul Giamatti, who plays John Adams, has terrible skin, everyone seems to talk in a whisper and sometimes I lose track of the words being spoken and can only wonder whether John Adams’ bad teeth made him hard to understand or whether everyone mumbled back then.

Photo by Wikipedia.

Though it’s not what she imagined, the first First Lady in the White House understands that the role of the public servant is to serve the people, not her own creature comforts.

And the scene I can’t get out of my head—John and Abigail travel to Washington DC, to oversee the transfer of the federal government to the District of Columbia and move into the White House (or the President’s House, as it was known at the time). There is no pomp or circumstance. The Adamses are transported in a simple carriage to mud covered grounds as hundreds of slaves look on. A single servant meets them and helps them out of the carriage and onto a wooden plank. They unceremoniously enter what will become the most important house in America and the house is a mess. The fireplaces don’t work and smoke fills the rooms. There isn’t enough firewood and they are constantly cold. There isn’t an ounce of glamor to this form of public service.

In a letter to her daughter mildly complaining about the lack of fire wood and bells to call the servants, Abigail says, “You must keep this all to yourself, and when asked how I like it, say that I write you the situation is beautiful, which is true.” Though it’s not what she imagined, the first First Lady in the White House understands that the role of the public servant is to serve the people, not her own creature comforts. John Adams writes in a letter to his son, “Public business, my son, must always be done by somebody. It will be done by somebody or another. If wise men decline it, others will not; if honest men refuse it, others will not.”

Most of us would agree, though deeply flawed, our Founding Fathers were wise men who created a frame for a political system that in many ways has served us well. In watching John Adams, I feel and see more deeply the cost of a commitment to public service. The long view of history reminds me that the $4.2 billion we spent on this last election is recent history. And it also makes me ask: Are too many honest men and women refusing public service, making room for too many politicians driven by ego and the desire for personal gain? And because this is what I do for a living, it makes me think about the history of the regional theatre movement—about our leaders, past and present.

And I ask: How do we currently as a field define our relationship to public service? We take a tax break, and like churches and libraries, we offer something of value to the public. When we say we choose to make our art in the context of not-for-profit theatre, we embrace a form of public service—not for the sake of glamorous careers that include arriving in limos to the Tony awards and sipping champagne with the stars. I intentionally chose to work inside not-for-profit theatre because I had a deep desire to effect change in the world. But somewhere along the historical path of the not-for-profit theatre movement, public service to artists and a community ran head long into private desires for personal success. Like our political milieu the public good has gotten confused with private desires.

In both editing the report, In the Intersection: Partnerships in the New Play Sector by Diane Ragsdale, just released by The Center for the Theater Commons, and attending the convening that the report covers, I have a deeper understanding of the movement of history in our field from a purer sense of public service to a market-driven desire to both serve and survive. These historical shifts in mission and purpose aren’t simple, and they don’t happen over night. We didn’t go from John Adams to Mitt Romney without struggles of every kind. But if you are invested in the future of the not-for-profit theatre movement, I suggest you read this report closely (you can download it for free), because it will place you in the thick of history whose next chapter will be written by the readers of HowlRound, among others. The meeting this report covers was, from my vantage point, remarkable. The participants are public servants struggling with increased market pressures—how to make a public good in the face of enormous obstacles. The report covers a historical shift from the very opening conversation between Rocco Landesman and Gregory Mosher, and that shift is more deeply explored in the second chapter in the conversation between Oskar Eustis and Robert Brustein. Eustis frames the very question that the report explores:

The meeting this report covers was, from my vantage point, remarkable. The participants are public servants struggling with increased market pressures—how to make a public good in the face of enormous obstacles.

What strikes me as you talk Bob is that . . . everything you’re talking about is about being part of a larger history that stems back really to that beach in Provincetown in 1920 through to the present. And you talk about being engaged in the training and the discussion and the creation at all at once so that, in a way, you are creating a world of values that is separate. And that world of values is part of a larger history; but we haven’t talked about profit or commerce in any of this really. And I think that one of the difficult things is: Where do you find an alternative set of values in the world—where you can live inside an alternative set of conversations about “profit and loss”?

In pondering this question we must consider the history of our own movement. We must consider the values and the words of the founders of this movement like Robert Brustein and Zelda Fichandler who are still around and able to guide us—and not just when it’s to our advantage to do so, but even when that looking back questions our practices in the moment. The group of twenty-six not-for-profit theatre representatives, commercial producers, and artists that gathered for this conversation did exactly that. And in the looking backwards and forwards, all of us in that room felt perplexed about where the not-for-profit theatre stands now. We asked ourselves how we had gotten from there to here and most of the not-for-profit participants, as you will read, were not convinced that here was what our founders meant when they argued that not-for-profit status made sense for the theatre.

In one of the many honest and soul-searching moments in the report, Tony Taccone, artistic director of Berkeley Rep, tries to make sense of how we came to this moment in our history: And so we’re trying to describe what happened to us. And trying to exercise a little bit of consciousness about where we want to go. Is there a creative progressive place we can go together as a community, as a culture? Because individualism, fame, money, materialism lead one another to an iceberg. But we all kind of need and want those things too; so it’s a really tricky road.

And so I sit here post-election pondering multiple American histories, the histories of presidents, and Constitutions, and theatre movements. And I don’t want to argue that things should be as they once were. We don’t look back in order to go back, but rather to better choose what going forward looks like. I’m so grateful for the evolution of thought that has created the possibilities for new stories, not the least of which is my new story as a legally married person. But in this post-election bliss for many of us, it makes sense for us consider why we value public service, and why we’ve chosen a life in the not-for-profit theatre. Have we done it to succeed on personal terms or do we make art to make the world better?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

To a certain degree, one might be left to ask about the relationship between the ability to effectively serve and the success drive. Does the drive for personal success exist out of a desire to fulfill the service mission espoused by folks in the nonprofit sector?

How difficult is it for a beginning artist to get an artistic director to return an email, for example? Might this person be driven to succeed, to beef up their resume/credits/network, in order to try and get to a place where the are positioned to try and make the world better? Is this a limitation of the way things are done at this juncture?

Spent this past Saturday morning facilitating a session at the National Federation of Humanities Councils' national conference in Chicago. It was a session for executive directors, folks who run state Councils al over the US, and are therefore responsible for curating and designing the programs that circulate throughout their states' communities, large and small, and encourage community dialogue. The leaders of 17 state councils were present. Red states. Blue states. Southern states. Midwestern states. Hawaii. American Samoa. Polly, i heard two things that your post made me reflect more deeply on. 1, someone said- " Justice is what love looks like in the world. Curiosity is what love looks like between two people." (i have no idea if the saying originates with her or not...) And another person said- " Dialogue isn't when 2 people hear each other- its when 2 people arrive at a point where, though what they believe and have to say may be different, their conversation is an agreed construction of something new, and necessary. In real dialogue, people hear each other, they say yes AND, offer, and continue. Anything short of that is lots of things, but dialogue isn't one of them." I think to me, the election doesn't represent a triumph of love over hate. It definitely doesn't represent a national dialogue. It feels more like a battle that was waged...I recognize (and am moved by) what has been gained, i feel slightly desolate over what i fear has been further lost this past cycle in the process of the battle. I don't think justice without curiosity is enough. I want both. Thanks for the dialogue you keep inviting us all into.

Michael,

Thanks for these thoughts. I'm so grateful for the energy you continue to put into clarifying what dialogue looks like. But I do struggle here a bit with something implied in how your talking about dialogue-- the idea that anyone who contributes to the conversation is bringing the possibility of dialogue to the table. That all contributions deserve a response of curiosity? When I think about certain threads of hate that filtered through this election cycle as legitimate positions of difference, well I guess I don't see it that way. In that moment I cannot divorce myself from the emotions of discrimination that I have suffered in those threads, and I can't find curiosity, even though I value curiosity more than anything. Perhaps this is why we need people doing the work you're doing on behalf of those of us who can't get past what feels like willful and intentional ignorance both in politics and in the theater.

i hear you. I so appreciate your generous response, in working to see my perspective as not oppositional to yours. I think there was difference in this election that was, at its heart, hateful and ignorant. But i think much of the difference maybe wasn't about that. It was maybe about fear. A lot about fear (which can certainly breed hate and ignorance, but i think the work there is different than the work of fighting willful and intentional...). I keep wondering about the power of love, of curiosity, alongside the power of standing strong for what one believes, to move battle to dialogue. Different fronts on a big complicated spectrum of movements for change. And i remain very interested in the relationship between our political discourse, and its difficulties, to how we do and don't move our culture field forward in times of stress and crisis. Also, i should say, the definition for dialogue i heard on this past saturday, I'm not sure i buy it fully either. But as someone who has been working with and around definitions of dialogue for a while, i am grateful when i hear one that makes me think a little differently...even if for a little while.

This is a really thoughtful conversation, avoiding hysterics, name calling and panic. Its the kinds of conversations becoming early threshold ,21st century, re-thinking of American Theater, its insular past, dismal present and hope forfuture... dismal

Polly -- A wonderful piece and well timed both as an epilogue to the election cycle and a prologue to Thanksgiving and the narratives of "service" and "giving" that are unleashed during the holiday season. I find I'm considering your questions in the context of higher education rhetoric that is increasingly entrepreneurialized (and like a good academic, I've made up a word to describe it) -- i.e. knowledge is only/best visible as a means to the creation of both a product and its market whether thats a material product (like a ShamWow) or the student herself as a product. This turn, in my view, comes perilously close to equating the service part of public service with customer service (which has an effect on how and why certain stories are being told vs. others not to mention the faces and experiences of the storytellers) and identifying the success of a company's "mission" to the growth of its market share, a market share that's measured first and foremost in red ink and black ink. Even as we work under the strictures of "non-profit" many institutions (educational and artistic) we have too long bent ourselves to commercial market rules and metrics instead of retooling and revising those for the specifics of non-profit contexts. I fear that the more liberal arts and performing arts students are urged to see even their education through commodified, simplistic input-output equations, it's going to be harder and harder to de-couple those mindsets from some of the values of origin for the non-profit theater world. This is not to say we don't owe it to those we train to be blunt and honest about the skills and ingenuity they'll need to "make it" but perhaps we can intervene a bit more vigorously on expanding the "it" they can/want to make.

Jules--there's so much rich thinking here. I think the point about costumer service versus public service is it's own article, hope someone will write it! So many theaters now are conflating the two by arguing what they feel they know their audiences want to see, making safe artistic choices and defending them in the name of customer service.

And then this question of education -- of the dual responsibilities of preparing students for the "real" world and equipping them with the thinking and creativity to make a world we as their teachers can't even imagine.

Thanks for this thoughtful reply, much more to think about!