Lest We Misforget—Chewing On Chewing On Beckett

An existentialist, a nihilist, and a feminist walk into a bar...Except that there is no bar, only a picnic table. And there is nothing to eat. Or to drink. And not everyone is able to walk, by the end. And it might not even end, really.

(In)famously, the estate of Samuel Beckett prohibits the casting of women in Waiting for Godot. Gleefully subverting both the spirit and the letter of this law, Ed Proudfoot liberally, literally, and figuratively plagiarizes from Godot for his all-female cast riposte, Chewing on Beckett. Structurally, Proudfoot mirrors and mimics the balancing act Beckett performs in Waiting for Godot with two acts, which each oscillate between tragedy and comedy. There are two pairs of characters who have twinned encounters in the two acts, punctuated by a pair of visits from a messenger. For Beckett's Vladimir (Didi) and Estragon (Gogo), Proudfoot offers Viola (Vivi) and Eloise (Lolo). The master/slave duo Pozzo and Lucky from Waiting for Godot become a mother/daughter pair (Paola and Becky) in Chewing on Beckett. The young boy messenger who keeps hope(lessness) alive in Vladimir and Estragon in Godot is contrasted with an Old Woman who enters each act in Chewing only to order Viola and Eloise to leave.

The bulk of Viola and Eloise’s dialogue comes from biographical facts about Beckett and historical information about the initial productions of Waiting for Godot. In a sly act of meta-plagiarism, Proudfoot grounds their conversation in a plagiarized text submitted by his “Godot,” a cheeky student named Corey who seemingly cites the work of male authors (like James Knowlson, author of the 1996 Beckett biography Damned to Fame) as she plagiarizes the work of her professor, Eloise. In the confrontation with Eloise that she and Viola endlessly re-enact, Corey takes the Hegemann defense. Helene Hegemann published Axolotl Roadkill in 2010 when she was just seventeen. The novel was initially lauded, and then just as quickly condemned when material amounting to roughly six pages within it was identified as plagiarized. Corey (allegedly) defended her theft of Eloise's words and ideas with Helene Hegemann's words in her own defense: "There's no such thing as originality, just authenticity." Perversely, Corey attributes Hegemann's defense of her own alleged plagiarism to Hegemann in the course of justifying her refusal to appropriately cite Eloise.

Chewing on Beckett extends the philosophical pedigree, perhaps most significantly with the postmodern feminist philosophy of Hélène Cixous (who is never cited in the play, though many male philosophers, including Kant and Heidegger, are).

Proudfoot's Eloise notes that the initial production of Waiting for Godot in the United States was billed as a "laugh riot," a promotional strategy wildly inadequate to the task if ever there were one. The subsequent Broadway premiere took a more realistic approach to selling Beckett's bleak philosophical meditation in two acts, recruiting audience members with the tag line "Wanted: 70,000 Play-going Intellectuals." Those intellectuals would ideally have basic knowledge of the nihilism of Nietzsche and the existentialism of Sartre.

Chewing on Beckett extends the philosophical pedigree, perhaps most significantly with the postmodern feminist philosophy of Hélène Cixous (who is never cited in the play, though many male philosophers, including Kant and Heidegger, are). Cixous enjoined women to escape the confines of patriarchal rhetoric by writing the body, abjuring masculine linear narratives and sentence structure in favor of narratives that eschew the standard story arc with its isolated climax, and that employ elliptical syntax. Beckett influenced Cixous, a novelist and playwright as well as a theorist. Waiting for Godot is notorious for its lack of plot: nothing happens, and it seems that no one has the capacity even to die, or to kill themselves.

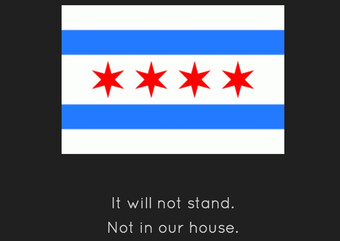

In Chewing on Beckett, Eloise repeatedly orders Viola to "dead me," turning an adjective into a verb, and eliding the act of killing by verbally skipping over it, to the desired post-murder/suicide state. Eloise makes up words that, in their context, emerge as equal parts neologism and malapropism, as when she notes that the Beckett estate threatened "sueage" of the (now defunct) People’s Branch Theatre in Nashville, TN, which had the audacity to perform Godot with female leads. Eloise quotes Corey's assessment of Beckett's work as crap, which produces, in the assessment of critics, meta-crap, and thus, "a bunch of crap trap." Pozzo and Lucky supply a carrot in Godot; Paola and Becky—in a horrible, parodic enactment of the Lacanian notion of feminine lack (of the phallus) and Christian self-sacrifice—saw off their own appendages and offer to prepare them as food.

I want to not conclude with some observations made by Cixous in her book about Beckett, which I am applying to Proudfoot's Chewing on Beckett:

"…in order to be alone, one must be more than one. Only the one who is accompanied, surrounded, pressed by solitude, feels alone. Alone keeps himself company in the vicinity of zero...what a story...it takes so long to be done, the end never ends, is never done."

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here