Masked and socially distanced, I entered through the dressing room, past a curtain, and into the theatre. But it was a mock dressing room, with cracked walls and tarnished mirrors, and a toy theatre built into a wall, with tiny seats, all empty, lit dimly by a ghost light.

“I am always standing backstage,” playwright Ellen McLaughlin said, as she began to tell me about a dream she had had. I was listening to her on a recording through the headphones they had given me, as I watched the tiny TV set on the tiny proscenium stage flash little black-and-white images of old performers. “Perhaps this is one of those Mickey Rooney/Judy Garland, ‘Hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-show!’ movies?” McLaughlin continued in my ear.

The playwright’s dream started sounding like the standard actor’s nightmare—McLaughlin was expected to perform a part that she hadn’t seemed “to have ever rehearsed, much less memorized…”—until it swerved, as dreams are wont to do. It became a performance by “long-dead elders” and “living strangers” sharing the stage, recognizing one another in their “different bad times and in [their] shared ache for something [they] can’t remember…” As Mclaughlin put it, “Here in the air of the theatre, livid with dust motes, we have always been one.”

Four minutes after I had entered, I left the snug, rundown little room—a stage set, really, but constructed incongruously in the center of the self-consciously majestic public space in downtown Manhattan called the Winter Garden. The room with McLaughlin’s dream was at the foot of the Winter Garden’s Potemkin-like steep, precarious staircase, amid its defiantly out-of-place palm trees, beneath the vaulted, sky-high ceiling, on top of the glossy marble floors. For all its airs, the Winter Garden is part of a shopping mall called Brookfield Place.

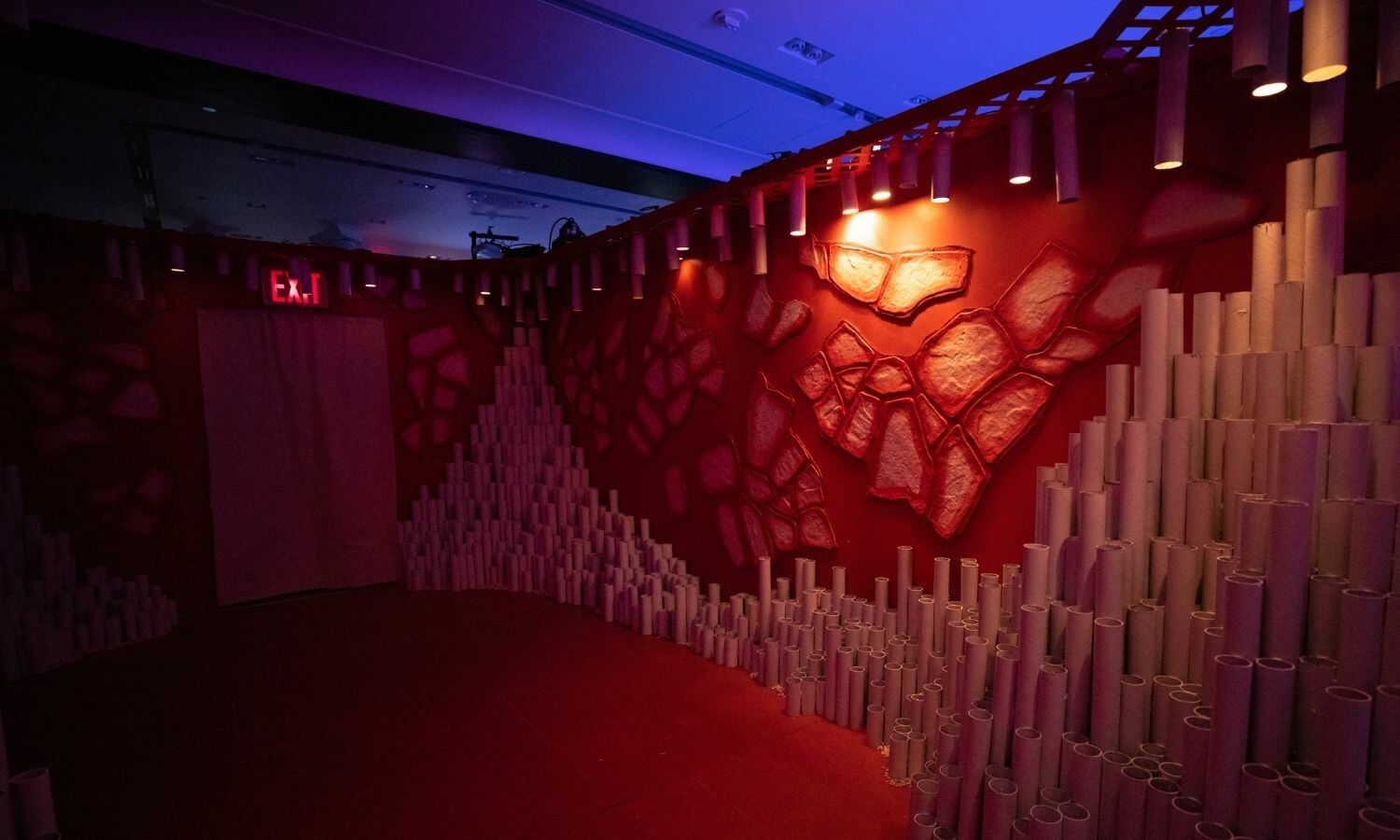

The house manager escorted me through this still sparsely attended temple of commerce to an unimposing corridor, opening a white door to the remaining rooms of A Dozen Dreams, a labyrinthine art installation built largely inside a former store in the mall, which sits across the street from the site of the World Trade Center, a previous worldwide trauma.

McLaughlin’s dream was one of the few explicitly about theatre, but it’s easy to argue that the entire project was an act of theatrical imagination—one, for all its modest budget, more breathtaking than the expensive mall in which it was located. It offered a literal look at theatre artists’ interior responses to the pandemic and even suggested ways in which the pandemic will change the art of theatre.

A Dozen Dreams was conceived shortly after the start of the pandemic, when Anne Hamburger, the founder and artistic director of En Garde Arts, best known as a pioneer in immersive, site-specific theatre, asked a dozen women playwrights to send her a recording of a recent dream.

“It was a simple response to the complexity of COVID,” said her collaborator on the project, John Clinton Eisner.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here