"Positation" in Action

Director Erin Ortman’s Multi-Year Journey with the Arabian Nights

Several coincidences align to admit me to design meetings, workshop readings, and rehearsal rooms for One Thousand Nights and One Day [OTNAOD], a musical based on Jason Grote’s play 1001, produced by Prospect Theater Company. Love for the people involved, the creative magic in rehearsal rooms, and the opportunity to spend time with the enchanting director Erin Ortman inspired me accept her invitation to observe her directorial philosophy in action.

We first met when I attended a Lark Roundtable reading of Caridad Svich’s play Fuel in September 2017. I was equally fascinated by Svich’s new play and by her director. Ortman set the terms, made space for creativity, and allowed everyone to be creative in a limited amount of time. Her skills and energy in the room left an impression.

We met in early October 2017 over coffee and pastries and soon hit upon the subject of her next project—a full production of a new musical already several years in development by Jason Grote and Marisa Michelson. I’d long loved Grote’s work as a dramatist and Michelson’s Eastern-influenced, ensemble-based musical explorations in Tamar of the River. I was curious about this collaboration. When Ortman named William Ball and his concept of “positation” as a core influence in her directing philosophy, I shouted in recognition and surprise—I’ve long been fascinated by Ball’s 1984 book A Sense of Direction: Some Observations on the Art of Directing. I wanted to know more about how all these pieces connected.

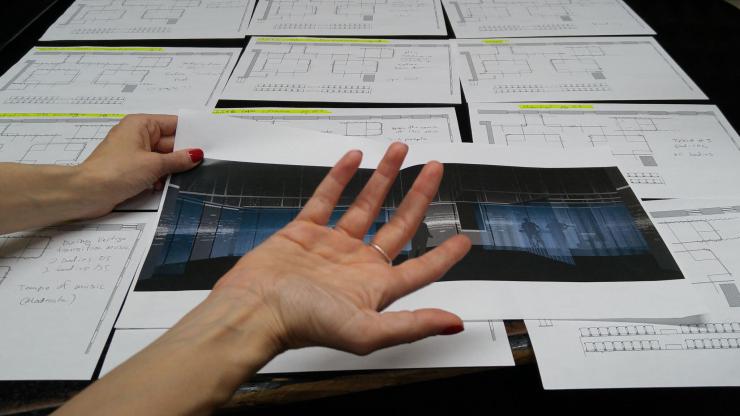

I began to observe the OTNAOD process with a December 2017 read-through, and attended workshops, readings, design confabs, the first rehearsal, and an early tech session over the following months. As expected, I was fascinated by Michelson’s approach to choral work, Grote’s dramatic influences, the movement team’s ideas, and the blend of design with storytelling.

I soon realized that Ortman’s directing process combined how she lived her life with how she created art collaboratively. What began as a meeting with a new friend ended as an opportunity to unpack a creative process with joy at its center.

'I so badly want the great ideas to rise. I don’t want anything to be told ‘no’.'—Erin Ortman

“There is only one story”—Themes and Structure of 1001 and OTNAOD

1001 is a theatrical tale of memory; mythic, literary, and cinematic references; relationships; and politics. The storyteller Scheherazade from the Tales of the Arabian Nights proclaims in 1001, “There is only one story, it has always ever been thus,” and these words appear as lyrics in an introductory ensemble number in the musical adaptation. Mythic Arabian characters in one scene hand off the storytelling to contemporary Manhattan twenty-somethings Alan and Dahna, who embrace and ignore cultural and political differences to find romance for a while, and then confront an apocalyptic event. Ortman reflected on the essential balance of the story layers of what the team referred to as “stacked time” in a December read through. “The stories open up onto each other, overlap and intertwine, each carrying equal weight.”

Scheherazade and other characters from The Arabian Nights, references to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, and poetic labyrinth imagery from Jorge Luis Borges combine in Alan’s fractured mind as he tries to put pieces of his memory together. “I believe that every character in the play is struggling to heroically save the world,” notes Ortman. “The stakes are very high nearly all the time.”

Choreography by Karla Puno Garcia and her associate Taylor McMahon continues this stacked and layered framework. Garcia noted in a December 2017 session that she hoped the movement would “help the audience to string together the worlds, between scenes, using movement throughout the piece to demonstrate Alan’s vital signs—breath and heartbeat and temperature—as a foundation for movement.”

The team learned that the simple set of the Denver Center’s 2007 production of 1001 helped the audience understand the story, while a more recent lab presentation of the musical was overladen with too many elements. Ortman told the team during a planning session, “We have to be cautious to not continue to build density upon density upon density and make the entire thing too much for the audience to comprehend.” The final simplified design by Jason Ardizzone-West and his associate Lauren Barber is based on curtains moved by the actors that define and redefine playing spaces, as diaphanous and flowing as the choreography and play structure. Ardizzone-West noted in a design meeting that “the transitions want to be part of the storytelling, which might mean that sometimes they want to be quick and sometimes they want to be drawn out and sometimes they want to be disruptive and sometimes they want to be graceful.” Again, balance.

Ortman and Ball: Philosophy in Action

At the December 2017 designer read through, Ortman calls for ideas to rise out of discussions and rehearsals. “I so badly want the great ideas to rise. I don’t want anything to be told no.” When I observe Ortman put this idea into action, I see her create a warm room where collaborators have clear intentions, where silence is allowed and trust is fostered, and where everyone believes that the best ideas will rise out of individuals working at creative peak energy. I hear William Ball in her style.

William Ball used “positation” to describe how to energize a room by supporting creative impulses. “By the principle of positation we say yes to every creative idea,” he wrote in the essay “Intuition, Creativity, Positation” in A Sense of Direction.

We accept this principle as a discipline because we have found that doing so yields practical results. What we are talking about has nothing to do with morality; it has nothing to do with ethics. We do not say yes to everything for virtue’s sake. We say yes because we understand that to do so is the practical way of sending a message to the intuition that every creative idea will be valued, respected, and used; and when the intuition gets that message often enough, it will send us its most perfect and its most pure creative ideas. That is why, whether we like it or not, saying yes to everything is the most creative technique an artist can employ.

Mentor Evan Yionoulis first handed this essay to Ortman during her MFA studies at Sarah Lawrence College. Yionoulis, then a directing professor visiting from Yale School of Drama, provided structure for Ortman in an otherwise very flexible program. “She taught technique and order with a great deal of creativity; creativity as fostered within order,” Ortman told me. And she provided the experienced Ortman a key to her practice. She’d been working as a director and teaching for some time before going back for her MFA, and Ball’s framework matched what she’d already been doing. The elements of Ortman’s directing philosophy, as we discussed and as I observed, seem rooted in Ball while drawing from a range of related sources.

‘You talk about peak creativity. If you say of course you can go home and be with your family, they’re going to come in so much more creative the next day. It’s all in service of this larger idea: making space, creating a culture where people are working at their best at the peak of their creativity, saying yes to people’s instincts, making room for people to be wrong and for myself not always to be right, listening instead of talking all the time. All of these things make room.’—Erin Ortman

Devising and collaboration.

Ortman admits that the time required for ideas to “emerge” in Ball’s manner is often in conflict with her role as mother to a young child. While she argues for her team members to have lives outside a rehearsal room (working reasonable hours and taking time with family), the number of meetings she takes imposes on her own family time. Cara Reichel, Artistic Director of Prospect Theater Company, has a long supportive association with the OTNAOD project, and notes that the amount of pre-production for this project exceeds what they usually see. But she doesn’t judge the process, and Ortman wouldn’t have it any other way. “It feels to me like the only way to work. I can’t think of another way of preparing this musical other than meeting for hours a week to talk about it.”

“Collaboration takes more time,” she notes, “but I know intuitively the best way to make theatre is to do it as a collective and to believe that the best ideas rise.” The beautiful part is, while supporting that emergence, she doesn’t have to have the best ideas herself. “It is not my job to generate the best ideas. It’s my job to invite and rise up with the best ideas. I rely heavily on my collaborators. I would never want to try to come up with all the ideas on my own and go in and tell people what I thought the thing should be.”

She realizes that her graduate school experience with devising gives her an ease with a world where no one is in charge when ideas are generated. “No wonder I want to talk to everybody for so long and want to hear so badly about their ideas. I didn’t practice how to do things by myself. I practiced how to do things together, and how to patiently listen to everyone.” And she learned how yield the floor. “If you were the person that demanded the talking stick for too long, you weren’t doing the work correctly.”

Framing trust, flexibility, relaxation, role modeling.

Ortman considers the role of trust and visioning as key to any production’s possibilities. “There’s a way to start working on a play where one chooses to not trust the material until something happens, not trust collaborators until they show they should be.” Rejecting this strategy, she would rather put the time in, bring the right people to the table, and put out another kind of energy altogether. “What about: these seven actors are perfect; this libretto is exactly what it needs to be right now; this this song is the perfect thing right now. Let’s just choose to have faith in the whole thing and work from there.”

Fear and distrust are destructive and combative. “There’s something light about offering up staying flexible, working with the peak of one’s creativity, trusting that the play will be good, believing that an actor can show up and do their best work daily.” She rejects the question mark of doubt for the exclamation point of faith in a starting point.

Actor hunches and heroism.

Ortman respects exploration and honors the actor hunch. “There’s a practice in the American theatre where we turn to the director for answers.” The actor often asks permission when they already have a great idea in mind. She favors turning the query around. “I find artists have the thing they want to do and will pose it as a question. Maybe as time goes on they will stop posing it as a question.” Politeness yields to respect in the rehearsal room.

She’s the wife of an actor and teacher of actors who believes in their intelligence and wisdom. “All actors are heroes. They will do anything to support the production. If they like you, they’ll do things to make you happy. If they want to try something, my god, let them try it. The best idea will rise. If you let an actor follow an instinct, it’s their intuition the whole time.”

Balance in life and art.

Ortman’s yoga, meditation, and belief in the collective in her theatre practice applies equally to her life outside. “There is something that feels holistic about the process; it aligns with how I lead my life,” she says, as we unpack how lives in the theatre are untenable for many practitioners. “We overemphasize theatre being the center of our lives as theatremakers.”

She is empowered by her freedom to question this paradigm and change it for her own productions.

I will not be a good director if I don’t see my daughter. I will be a better director for leaving at four o’clock half the week and putting my daughter to bed rather than working like a slave staying to seven every night. That nose to the grindstone attitude we have about the theatre I think is anathema. It doesn’t make better work. You talk about peak creativity. If you say, of course you can go home and be with your family, they’re going to come in so much more creative the next day. It’s all in service of this larger idea: making space, creating a culture where people are working at their best at the peak of their creativity, saying yes to people’s instincts, making room for people to be wrong and for myself not always to be right, listening instead of talking all the time. All of these things make room.

Directing is modeling trust and acceptance of process.

There is a great deal of role modeling that we do. I try to stay relaxed, I try to keep my feet on the floor, I breathe, I try to not rush. I believe that that role modeling matters. By not interrupting, less people will interrupt. By staying connected to my own breath, people are more likely to connect to their breath. There’s a great deal of power in how I lead, in the way I speak, and in the way that I hold my body. Stay open physically and emotionally to the miracles that are arising up in the room, and then people really start to trust themselves.

Lean In and Listen

The concept of the audience leaning in toward Grote and Michel’s layered stories of past, present, and future runs parallel to Ortman’s directing philosophy—the whole team leans into the craft, designs the world together, trusts that knowing and not knowing can exist together.

While all voices are at the table and valued, in Ortman’s view directors are most responsible for a project. “Actors can heroically perform a role, but if it’s a poorly executed production, there’s very little they can do to solve it.” Writers can craft the best work, “but if the director is misinterpreting their intentions, a play can sink.” The responsibility is countered by faith in possibilities. “I have faith that the space in which we make theatre is a sacred space. If our intentions are good intentions, the play will take on a life in honor of something good.”

Ball’s “positation” is faith in the possibilities engendered by good intentions. “A director who imposes things on his actors is usually giving them obstacles and is frustrating or binding their creative processes,” he wrote in A Sense of Direction. “That’s why we say, Impose as little as possible. Speak as little as possible. Encourage as much as possible. Say yes to everything. Allow Nature to work for you.”

Ortman loves this. “It allowed me to believe that the voice that arises in rehearsal and collaboration is the one that should be listened to. It’s about not talking so much. Answer questions with questions. Stop talking.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here