Raising the Curtain

An Interview with the Museum of London Archaeology Team Digging Up One of Shakespeare’s Theatres

Scholars of early modern English drama and Shakespeare fans were recently surprised by some of the findings announced by MOLA, which had been excavating the site of the Curtain Theatre in London. The Curtain isn’t one of the better-known playhouses from Shakespeare’s era, but it’s likely where his Henry V and Romeo and Juliet both premiered at the end of the sixteenth century. A number of the team’s findings were surprising, especially the discovery that the supposedly polygonal theatre building—referred to as a “wooden O” in Henry V—was actually rectangular. Here, I talk with Senior Archaeologists Heather Knight and Julian Bowsher. Heather has been leading has been leading the Curtain dig.

The Curtain is likely where Shakespeare’s Henry V and Romeo and Juliet premiered at the end of the sixteenth century.

Michael Lueger: Can you tell us a little about MOLA and about the team excavating the Curtain?

Heather and Julian: MOLA is an archaeological organization that conducts archaeological excavations across the capital and England and conducts research based on the findings of those excavations. We work on a number of high profile sites, including a number of Shakespearean theatres: The Rose, The Hope, The Theatre and The Curtain. All of our research is published in-house, with full details online at www.mola.org.uk/publications. As a charity, we carry work on community archaeology projects with an educational focus and we are an independent research organization.

Michael: Congratulations on the success of the excavation! Can you explain what the Curtain Theatre was and how it fit into the landscape (literal and figurative) of the early modern London theatre scene?

Heather and Julian: The Curtain was one of nine known playhouses in the sixteenth- early seventeenth century (the “Shakespearean period” is defined as 1567 to 1642). They called the outdoor venues [i.e., theatres like the Globe and the Curtain] “playhouses,” as opposed to “theatres,” which were indoor venues (e.g. Blackfriars). It was the fourth one we know of. The first one we know of was the Red Lion out in Mile End. It was built in 1567 but otherwise we know very little about it. The second was the unnamed one in Newington Butts, which we know was a building (probably rectangular) built in 1566, but converted/adapted as a playhouse by the actor Jerome Savage in about 1575. The third one, in Shoreditch, was confusingly called the Theatre and was about 200 yards north of the Curtain. This was definitely a purpose-built venue and the first as far as we know built in the iconic polygonal form.

We know very little about the Curtain—it was first noted as a playhouse in December 1577— and absent from a note about playhouses in the previous year. If it was not another polygonal building it might (like the Newington Butts one) be an existing building that was converted or adapted in about 1577. We do know a bit about the plot of that it was built on—a “field/pasture/close” called Curtain Close. The word “curtain” has nothing to do with theatrical curtains but refers to the encircling wall around the Augustinian Priory of Hollywell. The Priory was a large one that stretched from Curtain Road on the east to Shoreditch High Street on the west, from Bateman Row to the north and to Hollywell Lane to the south. Immediately south of Hollywell Lane was the Curtain Close, wherein the nuns kept animals. Like all the others, Hollywell Priory was dissolved in 1538 and a description of the Curtain Close refers to a field with stables called “the Curtain.” We know that by 1567 there was a larger “house, tenement. or lodge” known as the Curtain on the site. This might be the building into which a playhouse was inserted c. 1577.

So, Shoreditch was very much the first “theatreland.” Anyway, Shoreditch was much closer to the city.

The next development was on the south bank [of the Thames] with the building of the Rose in 1587, which was followed by the Swan (1595), Globe (1599) and Hope (1613). By this time there were two inns that had been fully converted to playhouses and a number of higher-status indoor “theatres.”

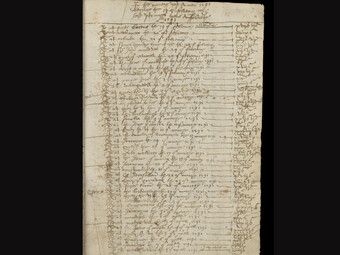

The known history of the Curtain is equally sparse—we have inserted extracts about the Curtain from Shakespeare’s London Theatreland (2012):

Evidence for the dramatic history of the Curtain, and which acting companies occupied it, is equally sparse. Apart from the fact that it was open for business from 1577, the earliest record of a playing company there was in a March 1584 petition by the City to close down the Shoreditch playhouses. This mentions the Queen’s Men (known to be at the Theatre) and Lord Arundell’s Men, who must have been at the Curtain. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men took up residence at the Curtain by September in 1598, when they left the Theatre and before they moved to the new Globe in mid-1599. Shakespeare was one of this company and thus will have known the Curtain, certainly; he is listed as an actor in Ben Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour, put on there in 1598. Moreover, it is almost certain that his plays Romeo and Juliet and Henry V were premiered at the Curtain. John Marston’s satirical Scourge of Villainy of 1598 hints at Romeo and Juliet receiving ‘curtain plaudities’. If Henry V was indeed premiered here, then the prologue reference to “this wooden O” would refer to the Curtain rather than the Globe.

Intermittently from c. 1620 until 1625 the Curtain was occupied by Prince Charles’s company, and they might have performed the play or ballad “The Man in the Moon Drinks Claret as it was lately sung at the Curtain, Holy-well.”

There is also one possible piece of evidence about the stage: Hector of Germany, which was certainly played at the Curtain, contains a stage direction to “sit on the rails.” These rails may be an early occurrence of the sort of small rails seen at the front edge of indoor stages in the 1630s and 40s. Finally, sometime between 1611 and 1615, the Venetian Antonio Foscarini, describing the visit of his servant to the Curtain, mentions audiences in the yard, in a “box” and in the galleries.

We also know that it was converted (or reconverted?) into a tenement block (a block of flats) by the 1630s and survived as such until the 1690s (last attested date 1698) and was probably demolished shortly afterwards.

Michael: Perhaps the most talked-about discovery from this excavation is your finding that the Curtain was rectangular, not the polygonal “wooden O” spoken of in Shakespeare’s Henry V. Can you explain what is so significant about this?

Heather and Julian: The remains that are being excavated suggest that it was “built” within an existing building. We do not know what shape the Red Lion was, but we do know that the Newington Butts playhouse was in an existing building. As such, it will have been a typical large courtyard house. Regrettably, with the conversion back into a tenement, it is unlikely that we will be able to recover details of the stage itself , though possibly [it was] just a rectangular building at the eastern end of the yard. The main door would (obviously) have been on the street front, and the stage would have been opposite. It’s not a big deal, it would not have affected styles of acting. The earliest ones we know about were tapered towards the front but later ones (from mid-1590s) were more rectangular.

Michael: Your discovery of a bird whistle has also attracted a lot of attention. What does this object look like, and how was it used?

Heather: We found the bottom part of the whistle; the top, which is missing, would have formed a small reservoir for water with a spout for blowing through. The warbling effect is created as the air bubbles through the water. These type whistles may have been used for sound effects in theatrical performances. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, staged at the Curtain Theatre in the late sixteenth century, there are numerous references to bird song.

The building itself appears rectangular, rather than polygonal, because of the walls we have found, some of which pre-dated the theatre and seem to have been incorporated into the building.

Michael: What other discoveries from the site are particularly important and interesting?

Heather and Julian: We haven’t actually found any direct evidence for the stage itself yet, but we know where it was located in the building and assume it was rectangular. What we do know is that the building itself appears rectangular, rather than polygonal, because of the walls we have found, some of which pre-dated the theatre and seem to have been incorporated into the building. We have also found the internal yard surface where the audience stood and entrances into the galleries on either side of the yard.

Michael: How do these discoveries build upon or complicate what we learned from the excavation of other early modern London theatres such as the Rose? What new questions do they raise?

Heather: Though this particular venue was one of the earliest, there is no linear development of the known London playhouses. Yes, most were polygonal though we know that another one of the “purpose-built” ones—the Fortune, built in Cripplegate in 1600, was 80 ft. square (the building contract survives and we know where it was but have not done any excavation in the area). The two inns that were converted into playhouses (the Boar’s Head in Aldgate in 1598 and the Red Bull in Clerkenwell in 1607) would have been rectangular. But all of these were much later than the Newington Butts conversion—and the Curtain as well.

Michael: What are some of the challenges of conducting this excavation in an urban area? Were there unique practical considerations that you had to keep in mind?

Heather and Julian: The main challenges are the depth of archaeological deposits (the theatre is about three meters below modern street level) and the proximity of adjacent buildings and the roads which need to be supported during our excavations.

Full details about MOLA at www.mola.org.uk

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here