The Reduta Theatre

Grotowski’s Forgotten Model

To my mind, Reduta was the most essential phenomenon in the inter-war theatre… I would say that Reduta is, in our aspirations, our moral tradition.— Jerzy Grotowski

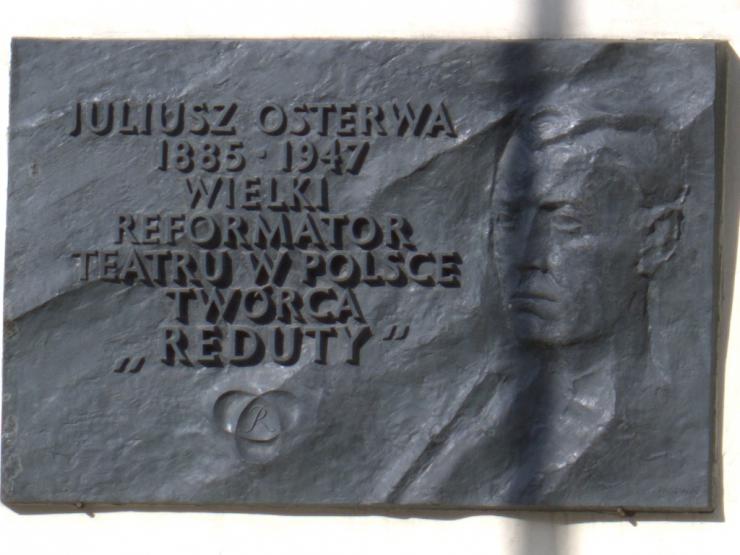

The Reduta Theatre was one of the most prominent theatres in Poland between the two World Wars, and was a major theatrical model for Jerzy Grotowski’s Laboratory Theatre. Yet, it is virtually unknown in the West. Juliusz Osterwa founded the Reduta Theatre in Warsaw in 1919, after returning to Poland from exile in Kiev and Moscow, where he had turned down an invitation from Konstantin Stanislavski to join the Moscow Art Theatre. From 1919–1939, the company operated at various times as a producing theatre, touring company, acting school, and institute of acting research from its bases in Warsaw, Wilno (Vilnius), and then back in Warsaw.

Theatre professor Kazimierz Braun writes in his article “Juliusz Osterwa—Polish Theater Reformer” that founder Juliusz Osterwa’s “work in Reduta, as well as his ideas, influenced Polish theater enormously. The intense research activity of Polish theaters in the 1960s, 1970s, and even 1980s, was based generally on the whole Polish theater tradition, but especially on Osterwa and his Reduta.” This essay will explore the influence of the Reduta Theatre on Grotowski and the Polish experimental theatre tradition.

The Reduta’s Influence on Grotowski

Grotowski explicitly stated that he saw himself as an heir to the tradition of the Reduta. Grotowski scholar Zbigniew Osiński writes in Grotowski’s Laboratory that, while “Stanislavsky’s heritage [of actor training and research] was the Theatre Laboratory’s and Grotowski’s key tradition in the sphere of the actor’s workshop explorations, the heritage of Reduta … was and is their fundamental ethical tradition”—and, he argues, this inherited ethical tradition has remained the “most durable” element of the Laboratory Theatre’s legacy.

Grotowski and the Laboratory Theatre demonstrated their identity as heirs of the Reduta through their choice of logo. Osiński notes that, as of March 1966, “the company of the Theatre Laboratory adopted the Reduta badge: a loop made up of two intersecting ellipses, the only difference being that the stylized letter ‘L’ was superimposed, instead of the letter ‘R’. From then up to the present day [1979] this sign … has appeared on all documents of the Laboratory.”

Photo courtesy of Cole Matson.

Grotowski himself spoke about the meaning of the Reduta logo for the Laboratory Theatre in a 1966 interview with J. Budzyński, quoted in Grotowski’s Laboratory (emphasis added):

"The Reduta loop...had the letter 'R' in the middle; we have taken it over without any change, except for the substitution of this letter by the letter 'L', for Laboratory. We have done this, first of all, because of our anger at the slighting way theatre people often express themselves about the monastic habits and naïve ideas of Reduta members. To my mind, Reduta was the most essential phenomenon in the inter-war theatre, because of its attempts to initiate long-term research concerning the actor’s craft and also because of its ethical premises which, as they were formulated in the language of its time, can now sound naïve, but which made excellent sense, because they tried to rid the theatre of the pretensions of the artistic demi-monde… I would say that Reduta is, in our aspirations, our moral tradition."

In order to understand this moral tradition, let us look at the principles of the Reduta’s ethic of theatre.

Principles of the Reduta

In his A History of Polish Theater, 1939–1989: Spheres of Captivity and Freedom, Kazimierz Braun places the Reduta within the tradition of “Polish Citizen Theater,” that is, theatre which is “based on the notion of service to the public and the nation.” Osterwa considered theatre to be “a holy communion, uniting actors and spectators in the service of one’s brothers and sisters, one’s nation, and God.” Theatre was a way of life for the company members, who lived in common and devoted themselves entirely to their work—a kind of theatre monastery. They were committed to the presentation of the works of the Polish Romantics, a group of nineteenth-century poets and playwrights who had kept alive a vision of Catholic Poland during the period of partition, and who envisioned a sacral role for Poland as a messianic figure whose suffering would bring about a resurrection of Christianity in Europe. Osterwa also used sacral language for the role of the actor at the Reduta. Braun writes that:

“Truth,” in Osterwa’s view, was the foundation for theater work, having both theatrical and moral aspects; acting, therefore was a process of revealing the truth of a character through the revelation of the actor’s own truth as a human being. Osterwa treated acting as a “sacrifice” or an “act of redemption.” The performance was for him a “sacerdotal sacrifice for the congregation.” He referred to spectators as “witnesses.” The “communion” between the actors/priests and the public/congregation was his goal, and the “actor-saint” was his ideal. He searched for methods to break the barriers between actors and spectators.

Braun identifies Osterwa’s first “commandment” of the theatre: “Theater is a holy communion; creating theater, you shall serve your brothers, your country, and God.”

In the year he started the Reduta’s acting school, the Reduta Institute, Osterwa disseminated An Outline of the Program of Reduta, which served as a statement of principles for the new school. It outlined the four following core principles, as summarized by Braun in “Juliusz Osterwa— Polish Theater Reformer” (emphasis added):

1. The truth is the main objective of theater work. Truth has a theatrical aspect, but most of all truth has a moral dimension. The ethics of the actor and his or her moral influence upon the public is of primary importance. The activities of all people involved in the theater’s work have moral and social functions.

2. The truth of an actor should be his or her own, personal truth, based on his or her own morality. The personal, individual morality of each actor is the foundation for the moral impact of theater, of the acting company, and of every performance. Thus, moral values are the core of theatrical creation.

3. The actor not only plays/performs—he or she rather commits an act of sacrifice or an act of redemption for the spectators, who are the witnesses of his or her sacrifice. The reality of theater should be not “a play for an audience,” but “a sacerdotal sacrifice for a congregation,” co-created with the congregation. The theatrical act, the act executed on the stage during the performance, is indeed not only an artistic act, but a sacred act too.

4. Theater is a deeply human art and is therefore an interhuman art. Theater is not only an art, but also an artistic communion between actor-priests and spectator-congregation.

In this outline, we can identify the following two major themes of the Reduta’s ethic: acting as a means of seeking and expressing truth for the actor, and theatre as a means of creating and serving the community through a shared experience of truth.

Both Osterwa and Grotowski shared the same hope of creating a transformative theatre, in which both actor and spectator would be united in a shared transformed community, and be empowered to go out and transform others through their shared commitment to truth and/or openness.

Grotowski and the Reduta Ethic

Grotowski took up the Reduta’s themes of acting as a means of seeking and expressing truth and theatre as a means of creating community through the shared experience of the actor’s truth. However, Grotowski did not take up the religious component of the Reduta’s ethic, seeking instead a “secular sacrum in the theatre” (“The Theatre’s New Testament,” Towards a Poor Theatre.)

We can see the inheritance of the Reduta’s focus on personal truth, sacrifice, and “interhuman communion” in Grotowski’s own language about theatre, as shown in the following examples from Towards a Poor Theatre. Grotowski’s definition of the theatre is “what takes place between spectator and actor.” He writes that theatre “cannot exist without the actor-spectator relationship of perceptual, direct, ‘live’ communion.” The pinnacle of performance is the “total act,” the moment during the actor’s performance “score” in which he completely reveals his deepest self to the spectator. The total act is “the act of laying oneself bare, of tearing off the mask of daily life, of exteriorizing oneself… It is a serious and solemn act of revelation…If the actor performs in such a way, he becomes a kind of provocation for the spectator…The spectator understands, consciously or unconsciously, that such an act is an invitation to him to do the same thing.…This is both a biological and a spiritual act.” This “self-sacrifice” of the actor’s entire being through the medium of his body in performance is, Grotowski writes, “the essence of [the actor’s] vocation.”

Just as the Reduta actor sacrificed himself in an act of truth-telling for a congregation of witnesses, challenging them to go out and serve the truth in their own lives, so the Laboratory actor sacrificed himself in an act of self-revelation before a community of witnesses, challenging those spectators to their own act of self-revelation. Both Osterwa and Grotowski shared the same hope of creating a transformative theatre, in which both actor and spectator would be united in a shared transformed community, and be empowered to go out and transform others through their shared commitment to truth and/or openness.

Besides this shared “ethic of sacrifice,” Grotowski emulated other aspects of the Reduta’s practice. The Reduta was Poland’s first communal acting laboratory, in which company members lived and worked together while experimenting in acting technique. Grotowski adopted this model. The Laboratory Theatre also copied the Reduta’s practice of touring shows throughout Poland (though the most visible heir of the Reduta’s touring tradition is Włodzimierz Staniewski's Gardzienice Theatre Association). Finally, both the Reduta and Grotowski shared an emphasis on Polish theatrical works, especially those from the Polish Romantic tradition.

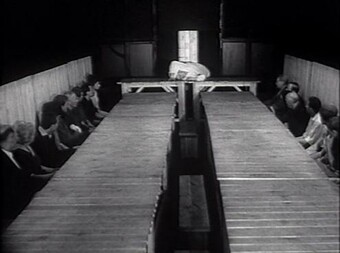

An example is each theatre’s production of Juliusz Słowacki’s adaptation of Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s The Constant Prince, which was one of the most famous productions of each theatre. Their productions, however, were very different. Where Osterwa placed a gigantic altar in an outdoor courtyard and used mounted supernumeraries to create a lavish spectacle, Grotowski stripped the Prince to a loincloth and placed him inside a spare rectangle of wood that suggested “something between an arena and an operating-theatre” (as Laboratory Theatre co-founder Ludwik Flaszen described the scene design in his program note to the production, reprinted in Towards a Poor Theatre). And where Grotowski confronted the Polish Romantic mythology of the Constant Prince as a symbol of Poland’s Christ-like suffering, Osterwa identified with that mythology.

This ideological difference—identification versus confrontation with the Polish Catholic national religious mythos—is the greatest contrast between the Reduta and Laboratory Theatres. However, Grotowski defended the Reduta’s monastic commitment to theatrical experimentation and its “ethic of sacrifice,” both of which he inherited in his own work. Through Grotowski, and other contemporary Polish theatre artists such as Włodzimierz Staniewski, the Reduta continues to influence the mainstream of the Polish experimental tradition. And Juliusz Osterwa, who saw theatre as a service to society and to God, lives on as that tradition’s nearly-forgotten grandfather.

Further Reading

Paul Allain, Gardzienice: Polish Theatre in Transition (London: Routledge, 1997).

Kazimierz Braun, A Concise History of Polish Theater from the Eleventh to the Twentieth Centuries, Studies in Theater Arts 21 (Lampeter, Wales: Edwin Mellen Press, 2003).

Kazimierz Braun, A History of Polish Theater, 1939-1989: Spheres of Captivity and Freedom, Contributions in Drama & Theatre Studies 64 (London: Greenwood Press, 1996).

Kazimierz Braun, “Juliusz Osterwa – Polish Theater Reformer,” Balagan: Slavisches Drama, Theater und Kino 1:2 (1995): 49-59.

Tadeusz Burzyński and Zbigniew Osiński, Grotowski’s Laboratory (Warsaw: Interpress Publishers, 1979).

Jerzy Grotowski, Towards a Poor Theatre, ed. Eugenio Barba (London: Methuen Drama, 1991).

Zbigniew Osiński, “Grotowski and the Reduta Tradition,” trans. Kris Salata, in Paul Allain, ed., Grotowski’s Empty Room (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2009).

Bolesław Taborski, “Introduction,” in Karol Wojtyła, The Collected Plays and Writings on Theater, translated and with introductions by Bolesław Taborski (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987): 1-16.

All material created by the author of this article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. However, all material quoted from other sources is subject to the original copyright.

Image Credits

Image #1 (Osterwa plaque): Attributed to Wikipedia user Gophi. Used with permission and shared under terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. (Source).

Image #2 (Reduta & Laboratory Theatre side-by-side logos): Image created by author from portions of images #1 and #3, and shared under terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Image #3 (Laboratory Theatre plaque): Attributed to Wikipedia user Heem will ihch. Used with permission and shared under terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. (Source).

Image #4 (Osterwa’s grave): Attributed to Wikipedia user Gapcior. Used with permission and shared under terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. (Source).

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here