Daniel Mesta: What makes your theatre practice distinctively Russian?

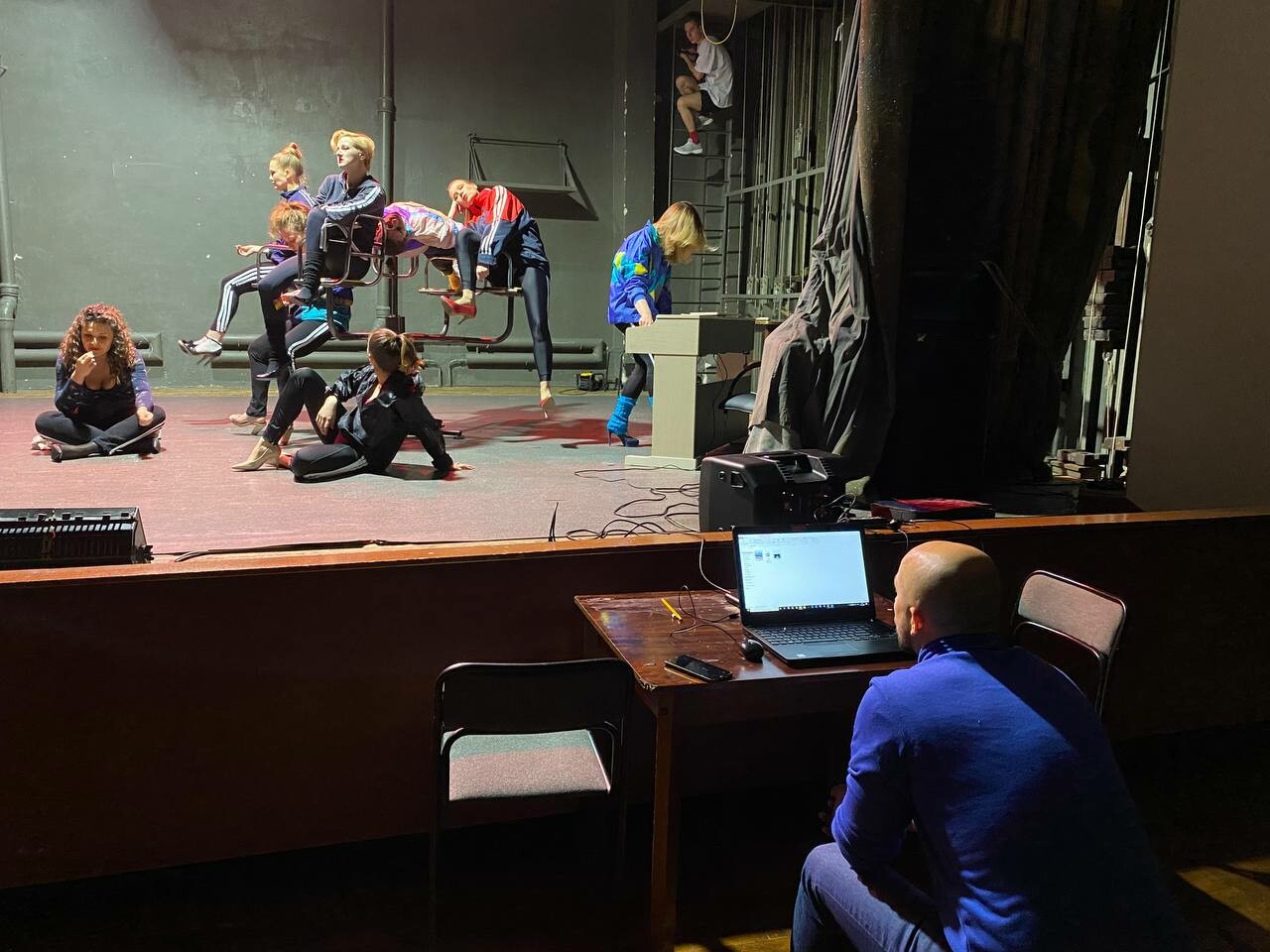

Vitaly Kogut: Great question. I think the most Russian thing I do in my practice is that I’m trying to discover traumatized things, which happened not to the characters but happened to me, and uncover these in my work. And that actually became the concept behind my teatr.doc work.

Daniel: Do you consider the theatre that you make to be particularly subversive or loud?

Vitaly: In some parts, yes. At some point, I understood that when you go through the mastery of text—for example, pure Russian classics like Nikolai Gogol… I realized that you want to say more. My personality wants to say more. That’s why I turned to modern plays that help me say more. That’s why my play Russian Lullaby happened. It manifested my political views, my country, my identity as a Russian.

Daniel: I want to talk more later about Russian Lullaby, but first can you tell me about your piece at teatr.doc? I’m sorry that it was cancelled.

Vitaly: Me too. It was a technologically innovative devised documentary piece about my own growing up in the forests of Russia. The original concept was a self-reflection of the artist, me, that was really a commentary on the intersection of my Ukrainian heritage, sexuality, and childhood experiences.

Artists need to connect with their heritage and the world around them because it is what fuels us.

Daniel: If the conflict in Ukraine had never started in 2014, what do you think you would be doing right now?

Vitaly: I definitely would be in Kyiv. I had the plan to go to Kyiv and start working there after graduation. In 2012 I started short trips there, and I understood that I felt really good there as an artist. It collided with the history of my family. Somehow it inspires me a lot. In 2004 and 2014, we witnessed two orange revolutions in the Ukraine, and I felt like something was changing, changing dramatically.

For the artist, I feel that it is so important to connect with this. Artists need to connect with their heritage and the world around them because it is what fuels us. You see, the unique thing about western Ukraine, despite its Soviet heritage, is the freedom. I don’t know how it works, but as soon as I got to Kyiv, I felt like I was related to this place. Old people talk like my father talks. I felt at home. The striking thing, when you go to the Kyiv of 2012, 2013, 2014, you understand that here things are possible—people are talking about change.

Daniel: What are the most harmful things you see Russian artists doing right now?

Vitaly: To openly support propaganda in your work. To try to artistically convey an idea of Russian supremacy over Ukraine and other parts of the world, which is happening right now, actually. I think it is a betrayal of your profession, of the humanitarian ideal of art. I see art as a humanitarian, liberating process. And this is counterproductive to that.

Daniel: What do you think Russia’s artistic future looks like?

Vitaly: I think that because of COVID and the practice of creating theatre works distantly—and now so with many great Russian theatremakers are abroad—Russian artists will get support from around the world to present their production in Paris, New York, Amsterdam, and other places. They are getting the floor right now—not after the war, right now. We will witness something new. This whole wave of Russian theatre is like the Russian soul that is infiltrating theatre life all around the world. I think Russian theatremakers have more to say right now. We are all wounded, injured, by this situation.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here