Toxic masculinity and consent have become so important to our national conversation, from the tidal wave of abuse disclosures coming out of the #MeToo movement, to the testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford at the Kavanagh hearings. Therefore, the stakes of interpretation are high when it comes to Laurey’s agency and Jud’s culpability, particularly because this production shows two white men vying for a black woman. Maybe recuperating Jud as vulnerable seemed artistically daring twelve years ago when Fish first directed Vaill as Jud at Bard. However, as theatre critic Vinson Cunningham recently noted, “in the past several years, we have undergone a radical revision in our understanding of male persistence.”

Journalist Alison Stewart couldn’t tell if Jud was more like a fragile, vulnerable “Kurt Cobain type” or a school shooter. Sarah Holdren and Elisabeth Vincentelli both describe him as an incel, the involuntarily celibate men who resent (and occasionally kill) women who won’t sleep with them. Frank Rich was enthralled by Jud’s anguish. Such ambiguity has political implications.

Listening to theatre critics argue about whether or not Vaill’s Jud is actually sympathetic helped me understand my confusion about the production’s take on white masculinity. It’s not clear if Jud is supposed to be pitiful, monstrous, or a pitiful monster.

The stakes of interpretation are high when it comes to Laurey’s agency and Jud’s culpability, particularly because this production shows two white men vying for a black woman.

I’ve yearned to see a production of Oklahoma! that truly listens to Laurey the frustratingly few times she reveals her inner thoughts. Early in act one, Laurey tells Aunt Eller (Mary Testa) that she locks herself in her room in fear because Jud lingers outside her window each night then sizes her up at breakfast each morning. Because Aunt Eller depends on Jud’s labor to run the farm (and maybe because she doesn’t think Jud’s stalking is a big deal), she gaslights Laurey by dismissing her fear and calling her a “crazy young ’un.” What if the audience was given time to truly imagine what it’s like for Laurey to be afraid each night and sexually surveilled each morning? This show doesn’t give the moment the time and space that it could. However, Jones’ apprehensive, distraught performance does a lot to undo Laurey’s reputation as a coquette and successfully depicts Laurey’s lack of options in life.

Describing the cast on WNYC, Fish posits that “everybody is both themselves and the character at the same time, and there’s both a kind of tension and a dialogue that’s going on.” With a Brechtian understanding of actors simultaneously embodying themselves and their characters, it’s worth thinking through how race is both present and absent in the production. For example, in terms of dream-ballet dancer Gabrielle Hamilton and Jones both being black in a majority white cast, Holdren argues that it is significant because “crucial but unacknowledged parts of Laurey’s identity get to come to the fore, explore the stage, and attempt to seek out their place — her place — in the world.” This duality made me think more deeply about Curly and Jud’s battling versions of white masculinity. Were their entitlement and resentment just two versions of the same person?

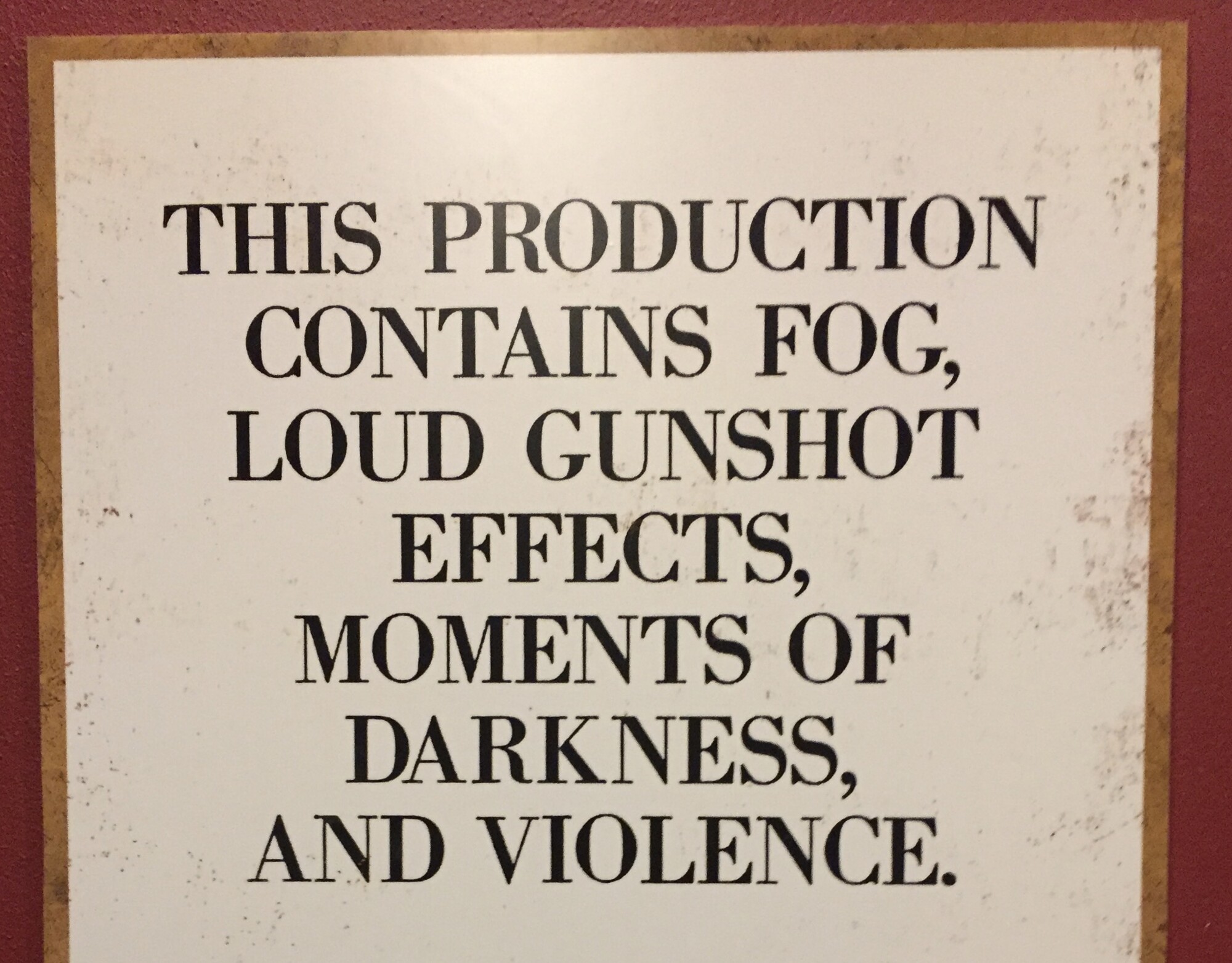

In act one’s smokehouse scene, Curly visits Jud’s meager living quarters to warn him away from Laurey. In Fish’s interpretation, the audience is plunged into darkness as the men whisper with heavy breath into handheld mics. An erotic charge grows as they deliver Hammerstein’s dialogue about Jud’s Colt 45 and porn collection. Eventually, a live video feed projects Jud’s face onto the wall in an extreme close-up that is both confrontational and empathic. When Curly’s face comes into the frame, it creates a literal tête-à-tête—the men’s mouths so close they appear to be on the verge of kissing. The scene’s smoldering tension and ultra-slow pace force the audience to sit deeply with them, elevating their relationship above any other.

Asked about reading Jud through a new lens, Vaill observes on WNYC, “This is a character that is called the villain and yet doesn’t actually do anything that …certainly not in the first half of the play… is even really questionable.... This has been decided for him.” While a new interpretation can animate an overly familiar work, I was not prepared for this level of disavowal. Is it not unusual to fire a gun inside when overcome with rage, to conversationally describe a local triple murder done in revenge for unrequited love, to ask a peddler to sell you a weapon, or to behave in a way that makes your own employer afraid of you? These are all things Jud does.

Fish and Vaill’s vision of Jud [is] as a sympathetic maligned outsider. This interpretation diminishes the true threat Jud poses and asks audiences to focus more on his misfortunes than Laurey’s predicament.

In more than one interview, Vaill has described Jud as being like Carrie at the prom, aligning Jud with the tormented protagonist of the 1976 horror film in which Carrie is elected prom queen only to get pigs blood dumped on her. Jud thinks he’s finally been accepted when he attends the box social with Laurey, only to have his outsider status cruelly reestablished. I contend that a more apt cultural reference for Jud lies in Jean, the valet in Strindberg’s Miss Julie who lusts after the woman of the house and resents the modicum of power that her class privilege allows. He’s decided he’ll overcome his circumstances by physically possessing her. As Jud promises himself in his solo song “Lonely Room”: “I ain’t gonna leave her alone!” In Oklahoma!, entitlement to a desired woman’s affections connects privileged and marginalized men.

Fish also stages Laurey and Jud’s struggle at the box social in the dark. The sound of wet kisses smack through the microphone. Is it supposed to sound consensual? There is no indication of resistance. Then the clanking sound of a metal belt buckle unfastening and a sudden shift. When the lights come up and Laurey fires Jud, calling him a dog and that someone ought to shoot him, he stands forlorn (hardly menacing) in the middle of the wide open stage space, the limp tips of his belt dangling from their loops. Rather than empowered, this choice makes Laurey seem impetuous and potentially cruel.

The choices become crueler. In Hammerstein’s libretto, Jud crashes Laurey and Curly’s wedding, says he wants to kiss the bride, grabs Laurey, and dies during a scuffle with Curly, who is then determined to be innocent of murder by an impromptu trial orchestrated by Aunt Eller. In this production, when Jud states, “Got a present for the groom. But first I wanta kiss the bride,” Curly looks chagrined but inexplicably gestures toward Laurey as if to say, “Well, if you must.” Laurey stands frozen and accessible to Jud’s creepy caress and then oddly passionate kiss. Why, exactly? The night I saw the show, murmurs of revulsion rippled through some members of the audience. It reminded me of Arthur Chu’s 2014 essay “Your Princess Is in Another Castle: Misogyny, Entitlement, and Nerds,” in which Chu dissects male entitlement and resentment. Why should a stalker ever get to kiss his object of desire one last time?

Jud places a gun in Curly’s hand, cocks it, and stands a few paces away as if to say, “Do me the favor of death.” Curly shoots, and he and Laurey are splattered with blood as Jud dies. The cast stays still as they flatly deliver the libretto’s dialogue of concern for Jud, which highlights their hypocrisy. For Fish, the choice “makes the community culpable, and…it probably makes the audience culpable, as well.” However, this is not the only thing it does. Casting against type, close-up video portraiture, removing Laurey’s overt premonition of Jud’s violence in the dream ballet, and staging Jud’s death as a point-blank murder without legal ramifications all cohere into Fish and Vaill’s vision of Jud as a sympathetic maligned outsider. This interpretation diminishes the true threat Jud poses and asks audiences to focus more on his misfortunes than Laurey’s predicament.

Several recent productions of Oklahoma! have unsettled the canonical work. In 2010, Arena Stage’s thoroughly multiracial production emphasized the themes of inclusion and national identity, while Goodspeed Opera’s 2017 production stressed Laurey’s vulnerability to an overtly dangerous Jud. Last year, Oregon Shakespeare Company’s sexually fluid vision manifested what David Cote called a “frontier utopia.” All of the productions used color-conscious casting to reimagine Rodgers and Hammerstein’s all-white Indian Territory. With so many productions circulating, why is Fish’s the one that made it to Broadway and will have a national tour? As iconoclastic as this production is, it is also familiar. Ultimately, it is safely canonical in its commitment to placing white masculinity at the center of US-American identity.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

In philosopher Kate Manne's book, "Down Girl - the logic of misogyny" she discusses this. She has coined the term himpathy to describe it, which I quite like. She defines himpathy as “inappropriate and disproportionate sympathy" given to white men (often men who have power, though that's not true of Fry) who exhibit misogynistic and entitled behavior.

sounds like more of the male lens. thank you for your essay.

dado

Hi Kitty,

Thanks so much for your comment! I appreciate your kind words and you taking the time to engage with this fraught material. Oklahoma! is certainly a complicated work. I love many of Rodgers' compositions but Hammerstein's libretto is definitely problematic for me. The play it is based on, Lynn Riggs' Green Grow the Lilacs (1931) is much clearer about the stress Laurey is under and the psychic damage that patriarchy and toxic masculinity cause her. --She is terrified of Jud and that's why she accepts his invitation to the party (she is afraid of what he will do to the farm and/or Aunt Eller and Laurey if he feels spurned). She is traumatized by the shivoree. Also, Aunt Eller doesn't really gaslight her in the same way. Interestingly, Riggs, who was of mixed white and Cherokee heritage, is ambiguous about the ethnic identity of the characters, but this is very different than whitewashing them.

It was hard to not write about the Riggs --> Hammerstein process in the above essay because I see it as key to understanding the politics of the 1943 musical. In addition, I see Fish's further softening of Jud as continuing Hammerstein's treatment of Riggs' play. However, I had to focus on the production itself!

Thanks again for your comment!

Chicago Tribune critic Chris Jones (a middle-aged white male and long-time enthusiastic fan of musical theater) did not like this production at all. (He even stated that he hoped "Kiss Me Kate" would win the Tony for Best Revival.) And I (a middle-aged white male and long-time fan of musical theater) have absolutely no interest in seeing it when it (presumably) comes to Chicago.

And I suspect most of the people who do see it (either the Broadway production or the touring production), regardless of age or gender, will walk away confused, disappointed, and even angry for having spent so much time on it when they were expecting a traditional production. (After all, except for the wheelchair the Tony award numbers seem designed to convince the nation's theater-goers that this was a traditional production.)

Further, in all probability the reasons this production went to Broadway and is getting an Equity touring production probably have to do with the producer and financing realities that have nothing to do with exactly how it was directed.

The real issue brought up by this production is something that has been bothering me a long time (and should bother others): Why it is that in theater and film the director is held in such high regard (compared to the writer[s]) and given such power to trash classic (or even new) works? For examples of this idolatry, check any number of lists or guides to movies and you will, in addition to the title and primary actors, see the name of the director listed -- but seldom the name of the writer.

In both film and theater the director has, for far too long, been given far too much power over works -- almost to the point of re-writing them. This "Oklahoma" travesty is the result. I suspect the reason so many people, from the general public (in terms of movies) to theater people (who should know better) so revere directors (while largely ignoring writers) is because the director is an authority figure, and people tend (alas) worship authority figures (politicians, priests, etc).

Whatever the reason, it has to stop. And that begins with (among other things) refusing to support productions such as this "Oklahoma".

Hi Neal,

Thanks for taking the time to read my essay and respond! It sounds like your primary concern with Fish's Oklahoma! is about directorial authority and aesthetics, whereas mine is with dramaturgy and politics. Would you say that is accurate?

I'm very interested in the question of authority and author-ity --as in, who has control and who guides the production into being. You've equated film and theatre as privledging the director equally but I'd say that the conventional wisdom is that film puts primacy on the director while US theatre, historically, puts more emphasis on playwrights and "serving" the text via the explication of given circumstances and character objectives. I don't have a foundational problem with "director's theatre," which sees the text as a springboard for exploration and the manifestation of a strong directoral artistic vision and is much more common in Europe. That said, I can't say I enjoy the oeuvres of Thomas Ostermeier or Ivo van Hove, who have become globally emblematic of this approach. On the other hand, I really liked Sam Gold's 2017 stripped down The Glass Menagerie. So, for me, I'm not against a strong directorial vision as long as I like the vision (!) and the director is willing to discuss the choices. (Also, as long as the directing process is ethical.)

I find it irritating that Fish repeatedly demurs from discussing the choices he's made by saying he hasn't changed anything in R&H's musical. To be specific, the words are the same. But the many changes are so obvious that I think journalists should press him on them. I have not read or heard any interview in which Fish is asked why it was important to his vision that Laurey be played by a black actor. Yet, it obviously is important as Amber Gray played Laurey in the 2015 production and Jones' understudies, Sasha Hutchings and Chelsea Lee Williams, are both black. In their separate interviews with Alison Stewart on WNYC, Jones discussed wondering about being cast but Fish did not discuss his vision about racial dynamics at all.

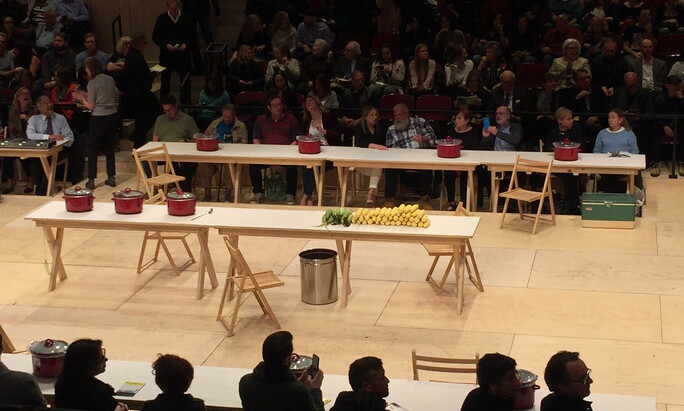

Are you referring to this review of Oklahoma! by Chris Jones that ran in the Daily News? If so, I wouldn't say Jones didn't like it. He does a really good job articulating how multifaceted the production is: "at once a shockingly brilliant and unstinting metaphoric exploration of our current collective condition and, for anyone still so invested, a deeply depressing dissection of all-American romantic ideals." I agree with a lot of his analysis, right down to the intermission chili and cornbread being "an act of communal feeding that feels weirdly at odds with the disaffected mood of a show for a country not doing so swell." Our nation is in a difficult place and this musical is about our nation. The darkness and anxiety of the production speak to that, which a lot of critics have noted. I wanted to write about something that had not been written about yet: how the recuperation of Jud as a victim rathern than a villan, and casting Vaill as Jud, combines with casting Jones as Laurey.

I think Terry Teachout's assessment of the production is perhaps the one that aligns best with my own, which is one of the reasons I linked to the "Three on the Aisle" podcast. He argues that Vaill's Jud is meant to be sympathetic and the only version of manhood the audience might want to identify with, whereas Elisabeth Vincelli argues that Vaill's Jud is s super creepy incel. Their discussion presents the distinction as an irreconcilable difference but I think they are both right and that's why I find the interpretation so questionable.

Thank you for this article! It succinctly sums up toxic masculinity while gaslighting, baiting, and ultimately punishing Laurey for existing near said toxic masculinity. I wasn't able to put into words why I didn't like Oklahoma! until I read your piece. Next time I enter a conversation about sexism in a beloved but problematic musical theatre, I'm going to reference this article directly.