Radical Hospitality

For most theatre companies, ticket sales amount to only a small percentage of their operating budgets. They rely on philanthropy, which is noble, but for that to succeed they have to find a way to integrate their work “into the larger tissue of the community life,” as one of the co–artistic directors of Ashfield, Massachuetts’ Double Edge Theatre, Carlos Uriona, told me recently, or else “the value [of our work] is reduced to a monetary exchange as an object of entertainment.” In an age saturated with far more convenient entertainment options, we cannot compete in the same marketplace. Barba puts it more directly: “The theatre as a whole has become an archaic minority genre in the panoply of our time’s performance forms.”

Still, what if we could work less like bookstores and more like public libraries—public libraries for live storytelling? Consider the path of Seattle’s Intiman Theatre, whose newly articulated mission is: “Intiman wrestles with American inequities.” I wondered how it manifests in practice. Artistic director Jennifer Zeyl explained:

If there is an education program, if there is a community event that we can hold up, if there is a town hall we can facilitate, if there is a conversation that needs to happen, that also is the work of the theatre…. It’s not just transactional. It’s a more relational mission.

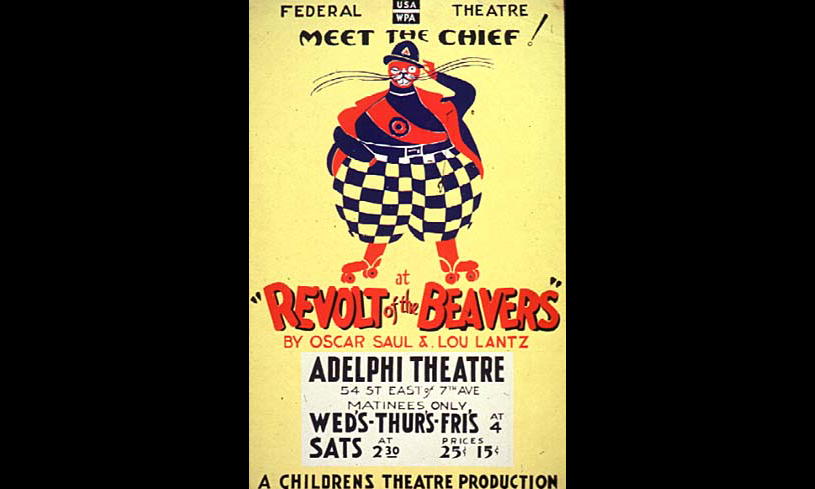

Intiman made news this spring when it announced their Community Ticket Project—inspired by Minneapolis’s Mixed Blood Theatre and their long-standing program of Radical Hospitality—making all their seats free of charge for their recent production of The Events by David Greig. (Interestingly, Intiman, a Tony Award–winning regional theatre, had gone out of business in 2011, closing its doors midseason and squeaking through an emergency fundraising effort in 2012 before reforming as a summer theatre festival. Since then, they have retired more than $2.5 million dollars of accrued debt and began this season debt free.)

As of one week before the opening of The Events, over 80 percent of tickets had been reserved online. Compare that to March 2019, when at the same point prior to opening Caught by Christopher Chen—which didn’t have free tickets—they were at only 5 percent reserved. It is clear the Community Ticket Project yielded an extraordinarily high advanced community response. But perhaps more importantly, “one thing we can tell already,” said Zeyl, “is that 70 percent of the folks who have logged in and reserved their free tickets … have never seen a show at Intiman.”

The Community Ticket Project also means that every performance of The Events, a play exploring forgiveness in the wake of a mass school shooting, features a community discussion. While it’s common for theatres to use talkbacks to engage audiences, at Intiman every member of their team—administrators, front of house staff, actors, and crew—received specialized training in how to conduct such conversations and deal with the wide-ranging opinions and emotions that would, no doubt, come out of the show. As Zeyl put it: “If you’re not trying to sell something, your staff has time to do a trauma-informed practice training with healthcare professionals because they’re not constantly trying to update the Twitter feed…. No one is good at selling tickets right now.”

Commodification is a distraction from doing the real work that our mission statements claim we do.

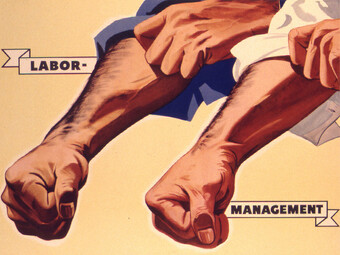

Relationships – Within and Without

Barba’s address also points out that the professional theatre’s struggle against commoditization includes “the manner in which a theatre imagines and develops its structure of internal relationships and interactions with the outside.” This is a model for the professional theatre that looks as much inward as outward. This is a theatre—despite our gig economy—that’s made up of committed, interdependent ensemble and community members. This is a theatre that pursues shared questions and communal points of inquiry over the course of years and multiple productions. This is a theatre that can risk pursuing enduring questions—a concept that remains vital despite being distinctly out of fashion at the moment—and has the freedom to set about its work with long-range curiosity and a sense of unknowing. This is not a theatre built around formulaic processes designed to churn out as many theatrical products as cheaply as possible.

Double Edge Theatre occupies a place in this section of the library metaphor. Founded in 1982 by Stacy Klein, it began as a feminist theatre and theatre laboratory, and today it produces exclusively original work that evokes Peter Brook’s “Holy Theatre,” or, as Brook clarified, “the Theatre of the Invisible-Made-Visible.” Double Edge prioritizes the physical, relational, and visual aspects of theatre as much or more than the audible, verbal, and literary. As it reads on the company’s website: “The prevailing theme of all of DE’s performances are the courage and necessity of the imagination in the progress and sustainability of human life.” Their productions challenge an audience’s expectations about what can be accomplished within the theatrical space. It is not about the form but what the form might reveal.

Similar to Barba’s long-standing ensemble at Odin Teatret, Double Edge Theatre’s core company members—artistic and administrative—train together rigorously and consistently. As co–artistic director Jennifer Johnson explains in an interview previously published by HowlRound, “[training is] the creative act rather than preparation for the creative act.” This highly physical training pulls from a host of sources and includes resistance training, object work (giant spools, cement blocks, balancing apparatuses), stilt walking, flying and aerial silks, plastiques, yoga, the exploration of archetypes, and, most especially, partner work. As Klein describes it:

You have the resistance of your partner; you can’t make your partner do what you want … so there’s a sense of real engagement and play. And then it’s developed to have a sense of risk … maybe you jump on someone’s back, or you walk on someone’s back, or you throw someone.

The focus is always on relationships and sustained connections, within and without.

Alongside their site-specific summer spectacles and touring performances, Double Edge hosts monthly training sessions for community members, weeklong intensives for theatre artists from around the world, and longer programs for apprenticing artists. Klein refers to Double Edge not as a theatre but as “a center of Living Culture.” Local relationships are as integral to the work as anything else. In her words, Living Culture is “playing music, dancing, gathering, talking, creating together, and participating in the theatre and other art that is created. On a daily basis, from childhood to death.” This is a theatre well outside of business metaphors, but, like a public library, Double Edge celebrates the intersections of its communities and flourishes when the doors are held open to everyone.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Having worked in admin or leadership in "non-profit" theatre for much of the last decade, I couldn't agree with the premise of this essay more.

My personal opinion is that we're headed for an economic paradigm shift in the business of theatre in the United States. Unless by some miracle, public funding becomes more of a thing, my suspicion is that the next sustainable model (at least for a generation or two) will be hyper-local, predominately original (or updated) work.

Like the article states, I don't think that will affect the Nederlanders of the world (or whatever theatre is capable of housing "Dear Evan Hansen" when it tours through), but for those creatives who want an outlet for their own unique voices, the nonprofit model appears to be broken - beholden to "safe" choices.

I'm actually quite excited about the future of theatre. I think we're entering into a new golden age of playwrighting with a multitude of perspectives that can wake up a sleepy industry - particularly in small and midsize communities and academia. But I also think it's probably going to be a rocky road, economically, for such creative voices - at least in the near future - while the new idiom is established with a new generation of theatregoers.

Call me cautiously optimistic about the future.

Thank you, Jadd. We're in a cultural moment that seems right for more original work with attention to local voices. The question is about the economics of that shift. How can theatremakers earn what they need to from that sort of work? The library model I propose is, perhaps, one step along the way, but it requires a commitment to incremental returns. Double Edge Theatre is an example for how local relationships can enable new work that reaches regional and national audiences, but it has taken a commitment of more than three decades for them to get there. I also don't mean to suggest that "scaling" is the only path to success, but our system provides few other models. The for-profit theatres in this country make a practice of capitalizing on other countries' public subsidies. The Guardian this week, speaking of Belgian director Ivo Van Hove, articulate's "Broadway's dirty secret" this way: "Its money-making machine depends on artists and productions nurtured by European government subsidies...when Van Hove is hired in the United States, Broadway producers are buying an artistic sensibility and a talent for provocation honed in state-funded theatrical laboratories across Europe, plus expertise that is the product of working relationships stretching back decades." In the non-profit sector, we have to find a way to provide for similar on-going collaborative relationships and innovations without public support. That will keep us on our heels until the "new idiom", as you nicely put it, finds a way forward. Still, I share your optimism that there is a way forward, rocky and slow though it might be.

I read the Guardian article in between posting my comment and reading yours. It's fascinating!

I've been wondering about this type of arrangement as an entrepreneur in the voice field. Case-in-point: I charge a per-lesson fee that is probably not affordable for the average artist. My bread-and-butter is high schoolers whose parents pay for lessons. No disparagement toward the young and funded, but if I'm trying to reach the artists of my community, I've either got to lower my rates (untenable for me as a working professional), or find some other way of funding the opportunity. I've considered crowdsourcing an annual salary and then teaching for "free", I've considered setting up my own non-profit with me as the sole employee, etc. etc. I think there are the resources available in my community of 120,000 people, but I've got to discover them...

BUT! If I do, how do I keep the stream sustainable? What if others start adopting the same approach?

This is probably the biggest unanswered question I have at the moment: How is the criteria for "worthy" determined? Art, by definition is unmeasurable. What makes my aesthetic more fundable than anyone else's? Is it a matter of administrative acumen? Is it a matter of addressing certain issues? I worry we start swirling the same "free market" drain, even if there's a public source of funds.

Having said all that, my theory on local (hyper-local) work allows for the idiosyncrasies of individual communities, which in turn allows for variability of strategy that creates wholly unique artistic landscapes. I am interested in whether a model can work the same in say, Spokane and Missoula, or if a completely community-specific approach needs to be considered.

Lots of big thoughts! Thank you for instigating them!!!