When the Invisible Illness Becomes Visible

This is the fifth installment of a series of interviews with theatremakers who have chronic illnesses. As a theatremaker with MS, my hope is that these stories will inspire all of us, and provide new approaches to resiliency for those of us living with a chronic illness. Here, I talked to actor/director Megan Simcox, founder of ACTive Roles in Ohio.—Sara Brookner

Sara Brookner: What are your chronic illnesses, and how did you learn about your diagnosis?

Megan Simcox: I was never super healthy. Going through college I started to think, "All my friends can do all of these things and they don't get tired and I just feel like I'm dying constantly.”

Sara: I can totally relate. Even now I constantly struggle with that feeling: “I'm just living my life, why is it so exhausting?”

Megan: I felt like I was getting hit by a bus and everybody else bounced back pretty quickly. Around that time I started having some weird symptoms, which could've been pre-MS. For years, I’d experience limb numbness on and off, but doctors and I always attributed it to something else.

I finally went to a new doctor in 2014. They ended up forcing me into the spinal tap and it was horrible. But that did clinch that it was MS and not anything else. I had gotten permanent damage to my cervical spine at that point and I've never recovered from that relapse. My legs are wonky ... I use a wheelchair but I also walk with canes some too. Some days I can walk fine without any aids but it's usually scary because you never know when all of a sudden I'll get this wave of numbness and fall over and break a bone or something.

Sara: You’re the first person I’ve interviewed who doesn’t identify as a writer. For anyone dealing with a chronic illness that causes a disability, that role has very different requirements than being an actor or director. What motivated you to start your own company?

Megan: It's like a culmination of the last fifteen years of my life. When I was a student at Ohio State I worked with a group called InterACT and they did outreach theatre on campus to help different groups. We did skits that shone a light on different topics, like sexual assault.

I shouldn't have to go into these places and bargain with them and tell them why their characters could be disabled.

I always thought that the community that I'm from in Eastern Ohio, right in the Appalachian region, could really benefit from a program like InterACT. The community has crumbled in recent years with industries declining, people losing jobs, and we’ve got a huge opioid epidemic. It's become very bleak. I really like the community but it's become very conservative and I see a lot of negativity, there's a ton of open racism, a lot of homophobia. I thought a program like InterACT could get the kids young enough and have that intervention with them theatrically.

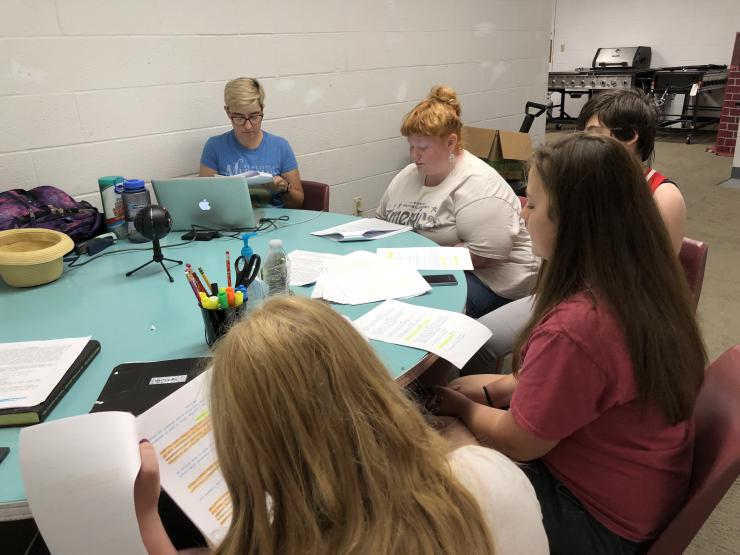

I came up with ACTive Roles Theatre Company a few years ago. We have a similar approach to InterACT: we’re an outreach theatre but I work specifically with children ages ten to eighteen. I offer free acting classes to them one day a week and we produce our own radio show broadcast on three different local stations. We also do Shakespeare in the Park each spring. These are kids that really don't have a lot of opportunities. There are no places to go see real legitimate theatre around here. It's basically community theatre that's run by a bunch of cis, white men. There's a lot of things that don't get addressed in the theatre community here because of that. I wanted to create an alternative theatre space where I do what I call equitable casting. I try to look at it from their identity, and how they’re going to get opportunities elsewhere. We get a lot of kids who are people of color, disabled, LGBTQ. We have a pretty diverse group. I don't turn anybody away. I focus on finding the kids that I know aren't going to get cast in their high school play or in the community theatre. They constantly blow my mind. I wish something like this would have existed when I was a kid growing up around here, I would have loved it. I get to direct the shows that I do with them and I'm the producer and director and writer of their radio program. All of this is volunteer; I don't get paid for any of it. I've been on permanent disability for several years now.

Sara: You’ve turned what could have felt like a huge setback into a meaningful way to not just spend your time, but to enrich your life and the lives of so many other people.

Megan: This was what I wanted to do from the time I graduated. Of course, with student loans I had to make some money, so I worked at a for-profit theatre for a while, and then I completely gave up on theatre after the recession. I lost my job and I went into marketing, event planning, and graphic design. If I could do it all over again, I wouldn't have switched career paths at that point, but the exhaustion from the MS was already blooming. My boss was nice enough that she kept me employed until I was able to go on disability.

I'd already dreamt of starting this outreach theatre but never had the time or money to get it started. I talked to a director friend of mine at Ohio University, and told him I really wanted to get back into theatre. I was very in a dark place when I got diagnosed. I was thirty years old at the time and it felt like my life was ending. I needed something to focus on, so I started stage managing for him. I told him I was interested in directing because I thought if I went back and got my master's degree I could have a job like his—he teaches acting classes and directs all the main stage performances there, too. I’ve joked that I could do his job with just my eyes and my mouth. It's a lot of work, but it's a lot of work that I could do from a wheelchair.

I started to change my direction from acting to directing. My chances of getting cast in any community productions are slim to none just because I show up with a cane. They're like, “We don't think that that's the agenda we want to push with this character.” It doesn't have to be an agenda, you know. But that's the culture of the theatres where I live. It's a fight that I don't have it in me to fight. I shouldn't have to go into these places and bargain with them and tell them why their characters could be disabled. If they don't have enough imagination to figure that out then I really don't want to work with them anyhow.

Sara: It sounds like the work you're doing with ACTive Roles is hopefully going to raise the next generation to understand that.

Megan: There is a selfish side to it too—I needed that to fall back on when I got sick because I was so depressed. When I started this organization, I was thinking, “I've got to do something with my life. I can't just lie in bed and watch TV for the next thirty or forty years.” That's not how I want to live. I'm a very active person.

Another part of ACTive Roles is getting myself into a framework where I'm prepared to think about entering a grad school. It’s like my entrance essay in grand project form. That's the selfish side of it.

Sara: I don't think it's selfish, I think it's smart.

Switching gears a little bit: one of the reasons I wanted to talk with you is because of how you commented on the last Chronic Theatremakers piece. You were championing it, but you were also disagreeing with the ideas around identity and language in a really respectful way—but passionately at the same time. And that never happens in the world of online comments! I was so impressed and intrigued. For instance, you mentioned how you prefer to use the word “illness” rather than “condition” and talked about the interplay between disability and identity. Tell me more.

Megan: On my good days, my illness is invisible. Those good days are very rare for me—a handful a year where I'm able to walk and not look like a zombie. I can identify with somebody who's had an invisible illness because mine was invisible and I lived for years not even knowing myself what it was. But now it's clearly visible, the way I walk and when I use the wheelchair.

I live in a really hostile environment, so I have to be my own advocate because people can be awful. There's a lot of erasure that goes into having something like MS. I like the word “illness” because a lot of times when I'm having a good day, people are like, “Oh, you look fine. There's no reason that you can't work.” There are actually a lot of reasons I can't work. Most employers aren't cool with giving you two or three months off to recover from an illness. Even if I had a PPO plan through an employer, I would still be responsible for $2,000 a month out of pocket for my medicine. So it would have to be a really good paying job to begin with. Right now I also live with my parents. I moved back when I got sick and my mom is my official caretaker. But if I lived on my own I would have to hire somebody else to come in and do those activities for me.

If I were to move to Pittsburgh and get a job in theatre, I would have to make at least $90,000 dollars just to be able to afford to live on my own, get a nurse, and afford my medicine. And I would still be living paycheck to paycheck. So having those voices come at me—“You look healthy enough to work, I don't understand why you can't work and I feel like you're just taking advantage of the government.”—I want to own the fact that this is an illness, it's not just a condition for me. This is something serious. It's a disease that could potentially kill me. In fact, my best friend’s mother passed away in January from the exact same illness. And so I think calling it a condition feeds those trolls who would be like, “You don't want to work because you've got some condition? Well, I got a condition too you know.”

Sara: There's a lack of empathy.

Megan: Yes. I'm really all about identity first language. I'm not a person with a disability. I am a disabled person. That affects every portion of my life. What I'm able to do, how long I'm able to be out of the house each day. How many chapters of a book I'm able to read before I start getting cog fog. If I had a more invisible illness or still able to work and conceal it, then I might feel differently. But it has more impact on my life than anything else. I'm also a non-binary person living in a really red area of the country. I'm morally opposed to shaving any part of my body. So I get a lot of looks from people at the pool and you’d think that would affect my life more. No, the disability affects me more than anything else. It affects what I'm able to do and it will affect my future. And unless they come up with a cure for MS, that will be the defining factor in my life going forward. I feel strongly about it.

I'm really all about identity first language. I'm not a person with a disability. I am a disabled person.

I don't want to tell other people how to identify. I know people who hide their invisible disability because they're worried they'll lose their job if their boss finds out. I completely respect that. But for the people who are out and open about their disability I do feel like if you're not putting disability first, then there's an element of erasure going on for all disabled people.

That being said, the spectrum of disability covers so many things. I had a conversation with a person a couple years ago about innate disabilities versus acquired disabilities. I have an acquired disability. I was healthy a good bit of my life and then I got a disease. Some people, like the person I was talking with who had cerebral palsy, it’s an innate disability that they’re born with. That changes how you function with and think about disability, too—when you have to live with it from the time you're born. And then you get into neuro-divergence and all the different intellectual disabilities.

Sara: The way you described founding ACTive Roles and all that you've been doing…I don’t want to diminish theatre’s role in your life by calling it a coping mechanism, but it’s also definitely something that helps you, right?

Megan: Very therapeutic.

Sara: But at the same time it's what helps you, if you're not careful it could be what hurts you.

Megan: Yeah. I can't overdo it. For instance: as soon as it gets above seventy degrees things start malfunctioning on me. My pain levels just go through the roof. Last spring I had done the first Shakespeare in the Park and really overdone it. And I'd also co-directed Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike. So between those two things, I hit a brick wall. I was in bed almost the entire summer last year. In fact, I didn't really fully recover until about November. I went to pride fest in Pittsburgh and it was an eight-hour day. I was in bed for six days after that—recovering from one eight-hour day. When I say in bed, I mean like in bed, mostly sleeping. I get up to go to the bathroom and I might go to the kitchen and get some water. This spring was much luckier—I was able to get an intern through the university who was my stage manager. She was invaluable to me. I got a lot more support from the community this year, too, putting the show together.

I don't feel nearly as tired right now having just ended a show as I did last year. Plus I only co-directed one rather than two shows at OUE this year. I had to dial it back and say, okay, last year it almost killed me, so what can I do this year to make it doable.

Sara: What advice do you have for people who are navigating their lives, particularly as theatre makers with various chronic illnesses and disabilities?

Megan: It’s important to become more socially aware and socially active and to be an advocate for all marginalized identities. That's going to lift everybody up. I truly believe that all oppression is connected. I wasn't always aware of that fact. If anything good happened because I was disabled, it opened my eyes to how oppression operates in a way that I didn't understand before I was sick. I think the future is going to be theatre activists who are social activists as well. I'm a member of ArtEquity, which has been one of the best experiences of my life. That organization is doing wonderful things and I think they're going to open up doors for people who historically have had those doors closed to them. I think the tide is turning. Kids today that are disabled or that might become disabled in the future, I hope that they'll have it better. I think that the more social activism people can participate in to lift up all marginalized communities, the more it helps everybody else too, including disabled people.

Push for inclusion. When a director says, “I don't want it to seem like we have an agenda by casting a disabled person in this role,” or “It doesn't fit my directorial vision,” or other excuses why it's their creative prerogative—I'm calling BS on that, and I think more and more people are too. That goes for people of color, for LGBT, and especially trans people and non-binary people. The more people that we see on stage in those roles, the more normalized it becomes and eventually that will be the culture and it won't have the stigma.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here