Beyond the Argument

Art as Antidote

This week, HowlRound is partnering with New England Foundation for the Arts in advance of our convening—Art in the Service of Understanding: Bridging Artists, Military, Veterans, and Civilian Communities March 10—12, 2017. This convening was inspired by artists who created five new performance works with their collaborators in the military, healthcare, and presenter communities, funded by NEFA’s National Dance and Theater Projects. This series asks: How can artists most effectively build relationships of trust as they engage in this work? What do military service members and veterans need to know to encourage them to work with artists? What do artists need to know about trauma in working with military and veterans’ communities?

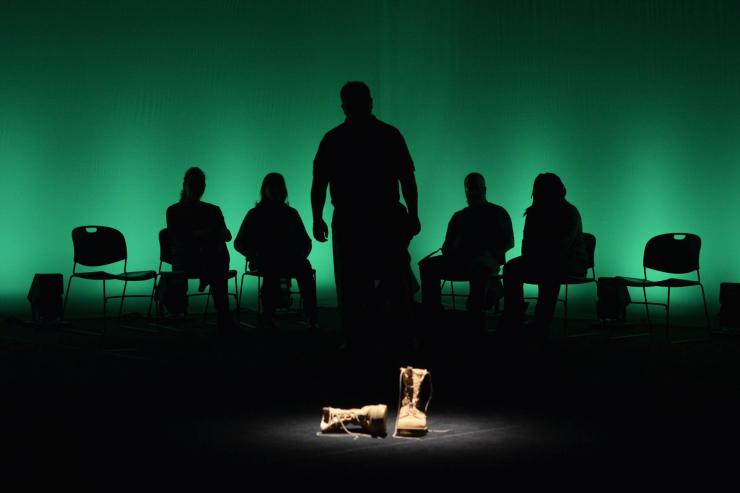

Through the Telling Project, Jonathan Wei has co-created with veterans in multiple US communities, extraordinary original works of theatre that promote military—civilian understanding. Jonathan is currently in rehearsal at the Guthrie Theater for the next major installment in this work. —Jane Preston, NEFA

We live in interesting times. The sources on which we once relied for information—the traditional news media—are struggling to understand their roles, let alone fulfill them. This situation is the eleventh hour of a long-unfolding epoch of Western thought, so long-unfolding that it is perceived as reality, rather than a moment. Our society can no longer distinguish opinion from information, and has begun to question the importance of doing so. This is the natural evolution of a reliance on argument as our primary tool for the processing of reality. The Socratic method, dogma, dialectic, scientific method, discourse, rhetoric, and debate—these are all approaches to reality that posit one perspective as superior to another.

Our reliance on argument and opinion is not simply the province of Breitbart and shock-jock radio. It saturates every element of our culture, it is the predicate upon which our academies are built, it is the way that we teach our children, it is the entirety of our governance and judicial processes, and it is the way that we start, move through, and finish our days. We are introduced to our conscious lives with “Don’t eat that because…” and ushered out with “Ashes to ashes” arguments about the nature of life. Consciousness is virtually indistinguishable from argument: we argue, therefore we are.

For the last ten years, I’ve worked with military veterans to transition their experiences in uniform to performances; in these performances, they portray their own lives.

War is a subject so volatile, so radical that it is impossible to use the word without physically and psychically feeling the pull and push of the forces of history, nationality, race, class, and religion, or hunger, fear, greed, and bloodlust. Our citizen minds react. We push back, we strike out, and we try to keep our equilibrium with arguments: war is bad; war is good; war is violent; war is necessary; war must end; and war will never end.

For the last ten years, I’ve worked with military veterans to transition their experiences in uniform to performances; in these performances, they portray their own lives. For all of the biases—the “War is” this and “War is” that—that I brought with me into this work, what I have come to see is that war and the military expand what we think of as human. As a species, we do, see, and experience things during war that are incomprehensible otherwise. Some are difficult. Some are wondrous. Some hideous. Some banal. War is as broad-reaching, polemical, and volatile as any singularly defined experience undertaken by our species. The military is as various and diverse a collection of humanity as will ever be encountered under a single rubric. Reeling before these immensities, we resort to argument—compellingly reducing this tremendous spectrum of action, observation, perspective, sensation, and memory to a series of small, discreet ideas. We protect ourselves from the indeterminacy of vastness, infinity, and variety.

In so doing, however, we stifle any kind of complex, invested engagement with war. We stifle our own human curiosity. And we place a large number of people and an even larger part of our history beyond our reach, in the realm of the unknowable, or unthinkable. Heroes or monsters; triumph or trauma; immortal or irreparable. Opinion supplants openness, argument suppresses inquiry, and we are all poorer for it.

War is as broad-reaching, polemical, and volatile as any singularly defined experience undertaken by our species.

As artists, however, we can return to the first thing, the thing before “War is…” to the inquiry: “What is war?” We can ask the question again, but this time, instead of rushing to an answer, or of wanting an answer at all, we wait, listen, and watch. We forget the impulse towards valuing one perspective over another, and let the bodies and voices that have been to war speak and move. We feel that movement, and we hear these voices in our own bodies.

This is the space that art can create. At this point culturally, it is one of the few spaces—and perhaps the only—in which subjects as significant and complex as war and the military can be addressed in a way that is not limited by necessities of arguments, nor stifled by the weight of opinion. Art doesn’t do this without deliberate discipline on the part of the practitioner. Without this discipline, art can easily capitulate to elegant and spectacular expressions of reductive sentiments.

But in a moment in which culturally we are careening toward radical polarity, art’s provision of a space for expansive and inclusive curiosity can act as a stabilizing force. Art can provide the opportunity for inquiry, immediacy, presence, receptivity, and vulnerability. It can provide a space for the expression of the primary desire to expand one’s world, to embrace rather than exclude, to experience rather than define, to immerse rather than to understand, and to contemplate rather than formulate.

In themselves, these opportunities are exciting. Contextualized, they are an approach to the self, the other, and the world that is distinct from the world of argument, from the rhetorical gesturing and posturing that comprise contemporary culture. They are a re-constitution of the self as fundamentally connected, rather than individuated; as primarily outward looking, and secondarily self-interested; as curious rather than knowing; and as absorptive rather than resistant.

And as has ever been true with art, these opportunities represent the way forward, to us being present and accountable to our histories, to the decisions we make individually and collectively, to our impact on our world, and most importantly, to one other.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I love readings that challenge my previous ideas of life and your piece has certainly accomplished that here. I had a preconceived idea of war and this incredibly messy feeling about it, which I generally try to avoid, but as in all mind opening practices, I should be breathing into the uncomfortableness, and exploring the reason for my urge to get away from it. I think the hardest part of that Is wanting it to be a simple, good or bad answer and that is, I believe impossible given the polemic nature of the subject. With this more open view and interest in being wrong about how I feel, do you have any suggestions as to the sources I should consider to feed my hunger for this this knowledge? Thank you for writing this piece and keeping the world on their toes, writers like you, are what we need in times like this.

Very well put, Jonathan. Thanks for sharing your thoughts and creative talents through The Telling Project!

Or, to quote the thirteenth-century Muslim poet-philosopher Rumi (as recently popularized by by Wayne Dyer): "Sell your cleverness, and purchase bewilderment."

Words to live by.

A beautiful, enlarging perspective with the courage not to judge. Thank you.

A beautiful meditation and sharing of your experience and observations. Thank you for taking the time to write this. Years ago at The Global Theatre Project we began asking the question "Who Is The Enemy?" another question with no direct answers... just deeper inquiry and that is a difficult idea to embrace. That we can live in the questions and in doing so can actually heal communities and grow as individuals. It takes courage to live there. War is so much a part of our world, our history, our nation that work like yours is vital. And sharing your process, your contemplation and your knowledge and insights necessary for us now.