Elements of Oz

Pay Attention to the Men Behind the Curtain

I recently revisited Sarah Ruhl’s book, 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, and stumbled upon her enticing assertion:

I think that in the contemporary theatre we don’t consciously think of our audience as an inanimate mechanism, but as digital media are more and more in our lives, we more and more imagine the audience as a camera and design as something to be photographed. This gives theatre a strange gloss, a strange preening quality as though it were about to be photographed. Whereas its charm is its very human gaze.

With Ruhl’s words ringing in my ears, I ventured to Elements of Oz, the latest multimedia extravaganza from The Builders Association, presented at 3LD in New York City, December 1-18, 2016, ready to feast my human gaze on this highly digital production and braced for the ideological clash. The Builders Association was founded in 1994 by Marianne Weems, and is known for its innovative collaborations, blending “stage performance, text, video, sound, and architecture to tell stories about human experience in the 21st century.” The Builders Association previously presented Invisible Cities at 3LD in 2007—another work that dovetails with the venue’s mission to “explore the new narrative possibilities created by digital technology.”

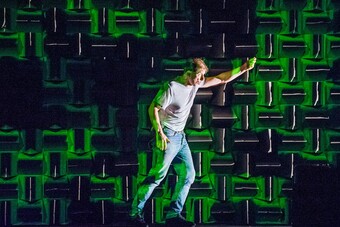

But for all the technical innovation in Elements of Oz, it remained a playful and extremely human show. The goal of all this technology is not glossy perfection but rather a digital upgrade of the mirror theatre eternally holds up to society. Elements of Oz is far from a simple tribute to or adaptation of the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. Instead, it exposes the man (or rather, men and women) behind the curtain through an endless fun-house mirror of revelatory effects.

This article purports to go one step further, by introducing those skilled purveyors of theatre magic whose talents too often go unrecognized, hidden backstage or in the booth as they pull the strings that animate the scene onstage. I spoke with Interactive Designer/Developer and Video Design Associate Jesse Garrison, Augmented Reality Design Associate Kevan Loney, Production Manager Brendan Regimbal, Augmented Reality/Network Consultant Larry Shea, and Video Designer Austin Switser to learn about their indispensable work on the astounding technology, design process, and hands-on manipulation during the show that brought Elements of Oz to life.

Elements of Oz pulls apart the original film and recreates the movie live on stage, in front of the audience. After shooting the film takes completely out of order on stage, the raw footage is fed through a software called Isadora, which immediately re-sequences, color grades, and sound mixes the film so that actors, technicians, and audience members all watch the reassembled scenes for the first time together during playback on stage.

Just as plastic and technicolor were new technology for film in the Great Depression, when the original ‘Wizard of Oz’ was shot, The Builders Association has found ways to incorporate the latest and greatest technology into their reconstruction of the story, giving their live audience the same communal mind-blowing thrill.

Switser says, “When you can incorporate longer shots or missed lines, that’s when the audience feels like you’re with them in the process. It’s a playful show, and so if actors break character or lose a line, we all enjoy it, we’re all up there having fun in doing it.” This playful spirit shone through in moments like when actor Moe Angelos, playing Good Witch Glinda, broke out into a very real laugh at the campy ridiculousness of her own acting. When her laugh played back minutes later, it felt like an inside joke for everyone in the room.

From the vantage point of the audience, one camera is visible maneuvering on stage, and we are aware of at least two more, one filming a long shot of the action happening on stage, and one somewhere backstage, filming Garrison’s hands manipulating an iPad. We simultaneously are called to watch the action on stage, video streams on seven different ceiling-mounted downstage televisions, one larger upstage television screen (primarily used for video playback), and one video stream in large format on the rear projection screen. Switser informs me there are in fact seven cameras on stage, and fourteen channels of video going. These channels are distributed among twelve monitors, the rear projection screen, and the Wicked Witch of the West’s crystal ball. There is also facial recognition software at work during a scene with Ayn Rand discussing the gold standard, superimposing the witch’s face onto hers.

And as if all that weren’t enough technical majesty to usher Elements of Oz into 2016, the company also developed an original smartphone app, which audience members were encouraged to download prior to arriving at the theatre and use as another interface with the action on stage during the show. The app inserted moments of augmented reality (distinct from virtual reality), YouTube videos, and sound effects in surround sound.

For those unfamiliar with the distinction between augmented reality and virtual reality, Loney explains, “Augmented reality is creating a virtual layer to merge the virtual world with the real world, which seems like both worlds are meshed together. Virtual reality, on the other hand, is completely blocking off reality. You put on a headset, leave reality behind, and dive into the virtual world.” Loney is on the cutting edge of these forms of technology, having studied augmented reality at Carnegie Mellon’s Graduate Video/Media Design for Theater MFA program, where Shea was his advisor.

Garrison is also currently studying the interplay between video and live theatre in his MFA program at CalArts, where Switser went for his undergraduate degree. Loney describes how applications of virtual reality are currently expanding in multifold ways, not only through entertainment companies like The Void, but also as a means of healing for PTSD and other severe trauma victims (see Lindsey Ferrentino’s play, Ugly Lies the Bone), as well as for military and medical training. As Loney says, “It’s the wild west of virtual reality right now, and everyone’s figuring it out together.”

The creative collaborators shared an enthusiasm for experimentation, and inviting their audience into the new world they were creating. The company did much to alleviate audience members’ anxieties about using the app during the show, providing portable phone chargers, helping audience members access the app on their phones, answering questions about Wi-Fi and airplane mode, and even starting the show with a short curtain speech by Garrison, explaining what to expect from the app. Garrison says, “It’s a delicate balance between putting people at ease and taking them by the hand. A lot of the response we’ve been seeing is people really feeling nervous about [the app], and wanting to make sure they’re doing it right.” On average, one to five people stop using the app during the show in any given group of sixty to seventy people who open it at the top of the show.

The company also developed an original smartphone app, which audience members were encouraged to download prior to arriving at the theatre and use as another interface with the action on stage during the show.

As a theatre goer with no shortage of death glares for other audience members who leave their phones glowing in their laps during a live performance, I, too, was apprehensive about inviting our phones into the sanctimonious theatre space. Shea says,

We are overcoming the sense that the theatre is a sacred space, where we should engage in idealized human on human interaction and all technology should be turned off. Marianne [Weems, Artistic Director], keeps saying, ‘Oz is the phone’ as a dramaturgical statement. We use these things every day and we don’t know how they work. Our phones are a literalization of our lack of control in the world.

By ceding control to my phone during the show, the twittering of chickens and munchkins arose from my own lap and my neighbors’ laps, I watched two excerpted YouTube video renditions of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” and I sat in the midst of a tornado, a forest of giant animatronic poppies, and a cloud of flying monkeys.

Regimbal explains the company was also interested in exploring the YouTube generation’s attitude towards ownership of material, through moments like the “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” cacophony in the app. Listening to Angelos spout off facts from her encyclopedic knowledge about The Wizard of Oz, I was struck by the idea that YouTube personalities have become our modern-day, technologic soliloquies. Technology is transforming our experience of personal relationships, and by extension, the way we behave in the theatre. We may not need to leave our living rooms anymore to access grandiose storytelling, but we do need to get out of the house to belong to an audience.

Just as plastic and technicolor were new technology for film in the Great Depression, when the original Wizard of Oz was shot, The Builders Association has found ways to incorporate the latest and greatest technology into their reconstruction of the story, giving their live audience the same communal mind-blowing thrill. Moreover, the film shot on stage is written over every night with each new performance, which allows them to remain true to their theatrical roots in creating an ephemeral show that can only exist for each night’s audience.

All five team members with whom I spoke expressed a deep gratitude for the highly collaborative model The Builders Association uses to create their works. Elements of Oz has been in the works since 2012, and the designers and technicians have been in the room for every conversation. As Switser attests, “You don’t work for the Builders, you work with the Builders.” Garrison agrees that the biggest joy of this production was the group of people, saying, “They’re some of the most passionate, collaborative, open, joyous colleagues you could ever ask for.”

When asked the same question, Regimbal highlighted a moment that had also struck me the night I attended; at the curtain call, all sixteen people who ran the show came out and took a bow. He says, “It’s not something I saw coming until opening night when we did it, and all these lovely people who worked so hard—normally we’re all hidden—get to be out there as curtain goes down and applause is happening, and it just feels like a great celebration of the act of making.” And that celebration, that theatrical exchange, that’s the human gaze at its finest.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Awesome article. The show sounds like real fun, and the technology is exciting. Would love to work with Augmented Reality sometime with The Living Theatre.

Great comment from Neal too. Balance is good.

Thank you Brad. Ironically, I actually came back to this page just now to apologize if my comment yesterday was inappropriate.

(A few years ago I finally watched a live production of "The Wizard of Oz" -- and I liked it more than I expected to [given my negative childhood memories of the movie]. In fact, for the opening scenes they used b&W sets and non-flesh-colored facial makeup to make it look like an old b&w movie... until Dorothy lands in Oz and everything is in color. So I finally understood what that transition was all about, and how it was indeed so dramatic!)

I am reminded of the old saying: "I disagree with what you say, but I'll defend to the death your right to say it!"

That pretty much summares my reaction to the kind of theater described above. Of course, I'm probably the last person on Earth who should comment about it given that:

1) Growing up I hated being forced to watch "The Wizard of Oz" every year on TV (a black and white one no less!);

2) In recent years I have become (despite [because of?] having a couple of patents!) a bit of a luddite, proudly having (for instance) never had a smartphone or phacebuk [miss-spelling intentional] account.

So naturally I can't resist:

1) Two decades or more ago I heard Goodman Artistic Director Robert Falls say (in response to an question from the audience regarding whether theater was going to survive) something so profound (if at first glance paradoxical) that I still remember it after all these years: "Theater is too old-fashioned to go out of style."

Alas, productions like the one described in the above article make me wonder if, in making theater not so old-fashioned, they are hastening its demise.

2) Common as (alas) the usage is, I object to the use of the verb "film" or "filming" when meaning "video recording". Few movies are still shot on film, and the only hope we have for it not going away completely is if we (especially reviewers and other writers) are all careful to only use the word when such use is accurate.