What is the Role of the Artist/Arts Presenter in a Community in Crisis?

Note: A version of this essay was presented January 15, 2016, at the Association of Performing Arts Presenters (APAP) Forum on Conflict and Culture. My presentation featured the accompanying video: “PLACAS: Healing Generations Through Theatre”

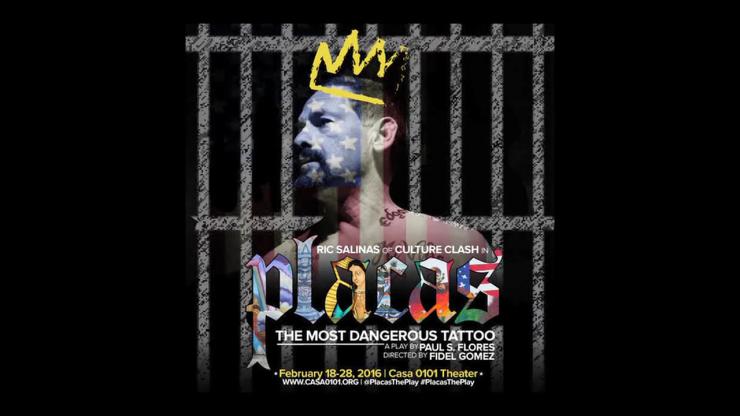

In 2009, I partnered with the Central American Resource Center, aka CARECEN, a health and social services organization for Central American immigrants in the Mission District neighborhood of San Francisco, and the San Francisco International Arts Festival (SFIAF) to create a play called PLACAS: The Most Dangerous Tattoo. CARECEN was running the city’s only laser tattoo removal program. Tattoo removal gives former gang members a second chance at life—to get a job, to go back to school, to be out with their family without fear that someone will recognize the tattoo of their set or affiliation and attack them over it. Laser tattoo removal is also a medical procedure, so the program at CARECEN was initially conducted through San Francisco General Hospital with direct support from San Francisco’s Health Department.

In July 2008, Edwin Ramos, an undocumented Salvadoran immigrant and suspected member of the MS-13, or Mara Salvatrucha, was accused of shooting and killing the Bologna family, a father and his two teenage sons, over a traffic argument in San Francisco. After his arrest, it was discovered that Ramos had twice been to San Francisco’s juvenile hall, and once to county jail, but was never reported to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), nor deported back to El Salvador due to the Sanctuary City policy that ensured that juvenile offenders were not reported to ICE. The Sanctuary City policy was developed in the 1980s when over a million Central American refugees were fleeing civil wars, many arriving in California cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco. The policy was meant to remove the fear that immigrants who reported crimes would be deported. It was a public safety measure to improve relations between immigrants and police, and help integrate refugees into the City.

After the backlash of anti-immigrant hysteria over the Bologna murders in San Francisco went to national news, Democratic Mayor Gavin Newsome was pressured to revoke the Sanctuary City Policy in 2009, and he also pulled city funding from the tattoo removal program at CARECEN. It was at this exact time that I was commissioned by CARECEN and SFIAF, with the support of a city funded San Francisco Arts Commission grant to create a play to humanize immigrants and Latinos caught up in gangs who were trying to positively change themselves through tattoo removal procedure, therapy, and second chance intervention programs.

CARECEN’s Executive Director Ana Perez connected me with Alex Sanchez as my main consultant to help me get interviews and educate me on the complexity of Latino street gangs—primarily the connection of MS-13 and other gangs to the civil war in El Salvador and its transnational identity spread through the US government’s intervention and deportation policies. I would also learn more about the conflict between Norteño and Sureño gangs, northern California and southern California, red and blue “colors.”

A former enforcer for the MS-13, turned founder of the intervention program Homies Unidos LA, Alex Sanchez, was a superstar in the gang intervention and peacemaking world. He was one of few who could safely cross over gang territories by offering services, jobs, tattoo removal, advice, food, rides, and even to cover funeral costs for homies in need. I shadowed him for nearly three years. Alex validated my presence with the homies in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and El Salvador, and I soon became his friend. So if his word wasn’t credible, if my word and my writing weren’t credible, if our collaboration did not help homies and represent their true hearts and stories, then we were all in danger. Grave danger.

“Society’s Most Despised Also Shows Love”

When I went to interview members of MS-13 and 18th Street gangs in El Salvador in 2009, a majority of whom had been deported from the US, they first sat me in a room. They closed all the doors and all the windows, drew all the blinds. They made a circle of chairs, put me in the center and began to interrogate me about why I wanted to interview them. It wasn’t the first time an outsider had come to learn about the harsh reality of gang life in El Salvador. The members had already been the subject of La Vida Loca, an acclaimed documentary that made its creator, Christian Poveda, a notable name on the film festival circuit. Yet the documentary’s subjects were all but forgotten. They were upset that they didn’t even receive a copy of the film.

The homies gathered told me, “We know you’re here because of Alex. We’ve been sent people like you before. Documentarians, photographers—they take pictures of our tattoos, they record us in our neighborhoods, then take it back and put us in galleries and festivals. They get famous while we die.”

So they asked me, “What are you going to do different, Paul?” I explained I was there to tell the story they wanted people to know about them. At the time, the US government had just named MS-13 as a terrorist organization. What did they feel about that? I asked them, “What would you like to see told about you?” And they said they wanted me to tell the public how they showed love. How they sacrificed for each other. How they took care of a disabled homie, gave his family money after he was crippled by a gunshot blast. Or how they would pay for his funeral if he was killed. How they would discourage younger siblings from joining the gang. How they stuck by each other. They had their own code of love. I promised to write about it.

Gangs are an effect of society’s failure to integrate the most alienated, the most wounded, the most despised. Alex Sanchez had been a seven-year-old unaccompanied minor when we came to Los Angeles to escape the war in El Salvador in 1980 with his little brother. After five years of being separated from his mother and father, Alex’s assimilation to US culture was painful, and never really took root. He joined MS-13 as a middle school youth and was in and out of juvie and prison, until he was deported in 1996. When he came back to Los Angeles, he was involved in the Rampart police scandal, and won amnesty from the US government. He won amnesty for many reasons: because Rampart Division police had planted evidence on him and had tried to kill him, because Alex had started Homies Unidos in 1999, because he had two children born in the US, and because his tattoos marked him for death in El Salvador, where the police double as masked death squads and kill young men with tattoos indiscriminately.

In October 2009, the FBI arrested my consultant Alex Sanchez in the early morning while he was still in bed at his home in Los Angeles, with his three children and his wife present. They indicted him on conspiracy to murder after the FBI had wiretapped his phone calls for three years. In October 2009, development on my play PLACAS came to a halt as funding for CARECEN’s tattoo removal program was pulled by Mayor Gavin Newsome, and my main consultant was held in federal prison on $2 million bail.

When we don’t acknowledge people—their background, their identity, where they come from, their history, their culture, their values, their presence—we are essentially rejecting them. What if you don’t know how to acknowledge others? How do you avoid conflict then? Here is a question for our theatres dealing with diversity issues.

“Solutions and Acknowledgement”

I have learned that most conflicts arise out of a lack of acknowledgement. When we don’t acknowledge people—we don’t acknowledge their background, their identity, where they come from, their history, their culture, their values, their presence—we are essentially rejecting them. What if you don’t know how to acknowledge others? How do you avoid conflict then? Here is a question for our theatres dealing with diversity issues.

In 2010, I was trained by the National Compadres Network to engage in the indigenous process of conocimiento, or what we might call acknowledgment, through the traditional practice of the circulo, with fire, sage, and song. The circle is where conflicts are meted out, and healing begins through acknowledgment: with every person speaking at their own pace about where they come from and what is important for every one to understand about their background.

Acknowledgement begins the process of healing. Healing happens when we acknowledge our brothers’ and sisters’ pain as our own.

Acknowledgment teaches you to listen and speak from the heart. We call it: palabra. Credible or honorable word. Acknowledgement begins the process of healing: listening to others in the circle helps individuals step out of the isolation that says you are suffering alone, that you must take care of all your problems on your own. The circle counteracts outdated bootstraps mentality. Healing happens when we acknowledge our brothers’ and sisters’ pain as our own.

In 2010, while Alex was still in federal prison, we received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to write PLACAS, based in part on the life of Alex Sanchez. Perhaps we received funding due to the fact that Michael John Garcés and Ric Salinas had both agreed to participate in the play. Twice now my play received funding from government resources while that same government attempted to suppress, arrest, and injure my sources. I can’t explain it. Nevertheless, with funding, new training in circulo facilitation, and a new purpose to create theatre whose goal was acknowledgement and transformational healing, I began holding a four-month healing circulo in 2011 at CARECEN with young Latinos on probation who were receiving mandatory tattoo removal treatment—this time with funding from a private donor. Once a week we would hold circle and use the National Compadres Network el Joven Noble curriculum to discuss how we acknowledge others, and learn to keep our word. I would bring in drafts of PLACAS and have the homies play parts and read it aloud. They would tell me where my characters’ actions were off, or were saying the words wrong. I didn’t know all the gang code then. I still don’t. The script became a highlight of the weekly circle because it showed how we could turn pain into art. It was a healing process for many, to look at their life outside the internal pain, and see potential for solutions. I offered to stage a production of the play starring the members of the circulo, but they turned down the opportunity—too shy, too risky.

Late in 2010, Alex Sanchez was let out on bail thanks to a national campaign titled WE ARE ALEX, which also utilized my play as means to promote Alex’s value to our community, and thanks to people like Senator Tom Hayden, who put up his house for collateral. We finished production on PLACAS and premiered it in September 2012 at the Lorraine Hansberry (now SF Playhouse) 600-seat theatre in Union Square San Francisco. We had to write for permission to the federal government so Alex could participate in the event. Agents came to the play and recorded everything Alex said. At the same time as we were opening the play, the two big gangs in El Salvador, MS-13 and Mara 18th St. had negotiated a historic truce between themselves and the Salvadoran government that reduced the murder rate in El Salvador by nearly 70 percent. This government-supported truce would last for nearly two years, until the next Salvadoran administration decided it would not support so called terrorists.

PLACAS would sell out, over four thousand people saw the play during the two-week premiere. We are now on our fourth year of touring. We have sustained the play by uniting with schools, social service and community organizing groups, subsidizing tickets through support from The California Endowment, a health foundation. We use the healing practices of acknowledgement and palabra in each community to ground ourselves in local issues. We also connect PLACAS to local policy campaigns and programs that address restorative justice, violence prevention, reentry services, immigrant rights, health access for all, and stopping the school to prison deportation pipeline. We were pivotal in creating a Fresno police youth advisory board, and reinstating the Sanctuary City policy in San Francisco. We also registered people for Covered California “Obamacare” in Oakland. This is our social practice theatre.

I am worried people who read this will think that because the result was effective, powerful, and successful, that this is easy. That I'm just an artist with a new approach. That what I do is so easily replicable. I have a new commission to address victims of police violence. And I don't know how I will pull that off. I can only follow my heart.

I can't teach artists or theatre presenters to love the people most hated by society. I can't teach policy makers to risk showing vulnerability, to love the people they punish with ridiculous racist laws, to be on the same level as those rejected by an oppressive society. However, if your heart does not break for the people most abused in this world, please don't talk to me about "community." You can call yourself an artist, or whatever, but this conflict is generations old, and until you all fight for justice, our society is at war. And the only policy that can truly change conflict is love.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks for these thoughtful and cogent observations.

Thank you for this article and thank you for your work. As an artist who works in prisons, clumsily doing my best to do the work ethically and responsibly, there is much that resonates for me about your work. I occasionally zoom out and remember how a misplaced word or a misunderstood handout can have very real, material consequences for folks inside. How it's easy for me to articulate an abolitionist impulse or describe restorative/transformative justice, but how I really can't escape my place of privilege in the conversation (and how, let's be real, even after years of this work...I don't know shit).

A few quotes in particular that hit home:

"Twice now my play received funding from government resources while that same government attempted to suppress, arrest, and injure my sources. I can’t explain it."

"We use the healing practices of acknowledgement and palabra in each community to ground ourselves in local issues."

And, most especially, this:

"I can't teach artists or theatre presenters to love the people most hated by society. I can't teach policy makers to risk showing vulnerability, to love the people they punish with ridiculous racist laws, to be on the same level as those rejected by an oppressive society. However, if your heart does not break for the people most abused in this world, please don't talk to me about 'community.'"

Anyway, thanks for the dose of inspiration.

Very cool. My pleasure. I'm wondering which prisons you work in? California?

Nope. I've visit the arts programs at San Quentin (legendary!). I've worked at three state prisons in AZ and I currently work at Draper Prison in Utah. Men and woman (and some trans* folks, actually) and all security levels...My next stop is Colorado. And I am hoping to eventually get into ICE facilities, but that's a whole 'nother ball of wax...

Mil Gracias/Thousand thanks, Paul S. Flores for this account. Our USA theater is overdue

for an aristic revolution nationwide, a dismantling of the commercial theater as a

temple of popular entertainment for well-off, middle-aged, college

educated anglo-saxons who can afford elevated ticket prices. Operated

mostly as a museum for established musicals, Anglo playwrights and producers who

provide a complimentary reflection of these audiences, a commercial theater worries

more about the bottom line, and a good return for it's investors. It's a business.

It takes money and real estate to make it work. But theater is also an art and belongs

to all the people, of all colors, to express their concerns and visions. Theater must, therefore, reflect

this diversity. Miranda's Hamilton is an exceptional, miraculous achievement

towards this kind theater. There are times, I must admit, when art is real good for business.

We need to stop explaining it for institutional theater community. In other words, integtation as a strategy for people of color to create theater or get funding for theater can be a painful and traumatic process. We have to "lead" from the ground up, not wait for top down "access".

Paul, I appreciate that you share your experience throughout this work with honesty and integrity. You acknowledge what you don't know or haven't yet figured out. This is feminist performance-making in the flesh. Thank you.

Thanks for pushing for it to see Cafe Onda publication, Emily.