Art in the Time of Fear and Loathing

The musical Hamilton and Lin-Manuel Miranda are synonymous with theatre, sweeping award after award after award—the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the MacArthur genius grant, a Grammy award, as well several Tony awards and nominations. This collection of accolades is no small feat and the collection will only grow as time goes on. Miranda is only thirty-six years old after all. In his now-famous Tony acceptance speech, with a quivering voice, he gave a moving performance of a sonnet he wrote for his wife Vanessa where he ends: “love is love is love is love is love,” while also referencing the tragedy of the Orlando massacre.

As he was giving his speech, the nation was in grief. I was also in grief, shell-shocked from the play I saw the night before at the Vineyard Theatre, an intimate 132-seat off-Broadway venue in New York City. I liked Hamilton (especially once upon a time when the price of the ticket was less than a hundred dollars), but it did not eviscerate me like Indecent did. I wonder if my evisceration was a result of recent events. Prior to seeing this play in June, Muhammad Ali died, the letter of the Stanford rape victim to her rapist went viral online, and then, right after I saw the play, hours later, the Orlando massacre occurred—the deadliest act of terror since September 11, killing forty-nine and wounding fifty-three people during Latin night in Pride month, with a majority of victims being people of color.

We live in a time when we need art.

The play Indecent is based on a forgotten part of theatre history recently revisited by Paula Vogel and director Rebecca Taichman. The play that Indecent was in conversation with was The God of Vengeance, originally written in Yiddish by a twenty-three-year-old Polish Jew Sholem Asch. The play is set in 1906 in a Jewish town where a father, his wife, and their teenage daughter live above the brothel that he owns. Determined to keep their daughter innocent and pure, they have a special Torah made. Yet, by the end of the play, their daughter is not only the newest member of the oldest profession, but also in love with a fellow prostitute. The Yiddish play was performed in many European cities including Berlin and eventually played in the Provincetown Playhouse in downtown New York in 1907. Then in 1923, it opened as a Broadway play with edits that changed the play’s fundamental spirit contained in “the rain scene” where the love between two women was both tender and unmistakable. By the end of the performance during opening night, the cast of twelve actors and the play’s producer were arrested, indicted, and convicted of indecency and for giving an immoral performance.

Vogel read the play when she was twenty-two and wondered how Sholem Asch, a young married man of Orthodox Jewish background could write such a play. Decades later, she met Taichman who was doing her Master’s thesis in Yale School of Drama on the controversy that surrounded the same play, and they decided to collaborate on this work. Since the beginning of their collaboration, the play was commissioned and presented at the Yale School of Drama, La Jolla Playhouse, and at the Vineyard Theatre.

Many of the artists I have met on the page, on the screen, on the stage, and in life are queer and their lives are arias and symphonies singing the truth.

Besides Vogel’s elegant writing and Taichman’s evocative direction, the strength of the production is how the play is presented. As critic Frank Rizzo writes in his American Theatre Magazine review on Indecent, “the power of Asch’s original play, as well as the power of theatre, are presented in profound ways. This is a play about a play in which people are transformed in ‘a blink in time,’ as the ownership of a piece of art transfers from playwright to audience.”

In addition, Vogel’s play extends far beyond the events in Broadway and the court’s ruling. One of the most emotionally resonant scenes in the production in fact is seeing Asch’s play kept alive by people who believed in it in a ghetto attic under Nazi rule where pieces of bread are shared as the play is performed—a metaphor for how art, especially in times of fear and uncertainty, is the bread of life from which we partake.

Today, the beat of expelling bestial viscera just keeps on going; in fact, it’s relentless. It is so relentless that I am changed, rewired. We live in a time when we need art. A few days after the Orlando shooting at the Stella Adler Studio, Toni Morrison, in the company of Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Sonia Sanchez, reminded us that “art is dangerous” because artists “sing the truth.”

If the message is the truth that we are trying to hear, then we should not shoot the messenger. Many of the artists I have met on the page, on the screen, on the stage, and in life are queer and their lives are arias and symphonies singing the truth. They have pushed me to attempt to live and to question the construction of the world as we know it. James Baldwin taught me beauty in prose and truth. Paula Vogel taught me that art does not exist in a vacuum and that there is always a conversation with the past as far back as Aristotle, and creating theatre also means participating in a bakeoff of sorts. Ocean Vuong taught me that love, in all its simple and complicated forms, is a mystery and that it is this mystery that compels people to fear it or embrace it. Jose Antonio Vargas taught me the difference between “undocumented” and “illegal.” André DeShields taught me to temper my anger by listening to Nina Simone, and Ping Chong taught me to honor stories of the voices we don’t often hear.

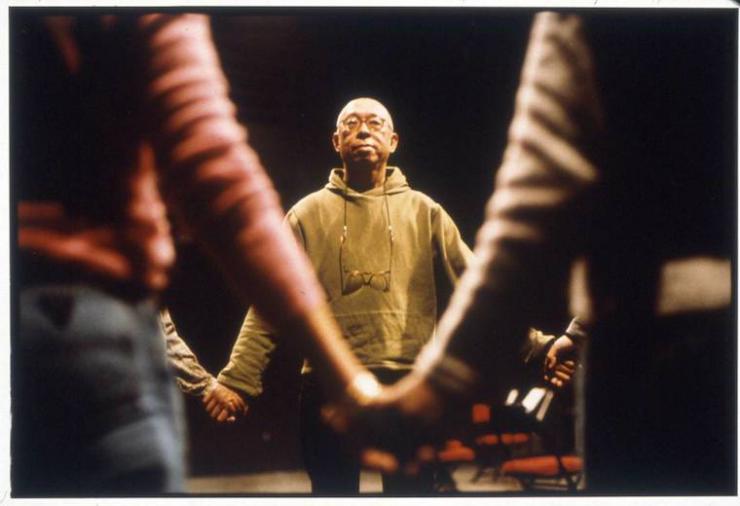

My story in theatre began when I was nineteen; I had an identity crisis because I was an immigrant of Chinese and Filipino descent, and I was born a girl. A gay man interviewed me and decided to put me in his Undesirable Elements show (which turned out to be his on-going signature series of documentary theatre) so that I could tell my story of being a Chinese-Filipino immigrant girl. Because he had a vision to let people tell their stories, Ping Chong has been changing lives one story at a time including mine. His most recent project is a documentary theatre piece about several intersections in the Muslim community called Beyond Sacred. Even the White House recognized his work; last year, he and Stephen King, among others, received the National Medal of Art from President Obama, who praised him “for his contributions as a theatre director, choreographer, and video and installation artist. Mr. Chong’s innovative performances explore race, history, technology, and art to challenge our understanding of humanity in the modern world.”

Without a queer pair of eyes, the world as we know it would not be as beautiful. These eyes, they teach us how to see the world. Though Hamilton deserves its accolades and, in the short time that it has been in production, it has already endowed a generation with a renewed sense of Americanness, of rising up to set the bar of what it means to be American by revising our understanding of history and quite literally how that history is performed. Yet it was Indecent that eviscerated me. I have never been to a performance that rendered me paralyzed in my seat after experiencing it. I was weeping, feeling my mortality in the marrow of my being, knowing that we come from dust and that we will return to it. The purpose of our life is to become human because it is obvious, at times, that we are not.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

"Modern man is the missing link between the ape and the human being."

Taylor (Charlton Heston)

"Planet of the Apes"

(opening monologue)

I just realized the movie came out (alas) nearly fifty years ago, and thus I should probably point out, for those who aren't familiar with it, that by the end of the movie Taylor comes to realize that -- despite how incredibly flawed it is -- humanity has much more value that he ever gave it credit for.

I think my own life (and perhaps that of many others) has followed a similar path.

I just got chills reading that!

Beautiful, powerful. Thank you for sharing this with HowlRound.

Thank you for the comment, Michael!