From Impulse To Audience

Four Days at Toronto’s Theatre Centre

West Queen Street West, March 2015

I’m here in Toronto to visit an old building turned new. After a more than $6 million dollar capital campaign and a year-and-a-half long renovation, the 107-year-old building at 1115 Queen Street West in Toronto is the new and permanent home of The Theatre Centre, Toronto’s premiere performance and live art development hub. The Theatre Centre was founded in 1979. My hope is to speak with artists who have made the Theatre Centre their home, and to explore what sort of impact it is making on the Toronto theatre community.

The 1.2 mile long West Queen Street West area of Toronto is a very trendy neighborhood in a city not usually known for its trends. On Queen Street West itself there are not one but two boutique hotels within a block of one another. The area boasts more than 400 businesses. There are coffee shops that would give Brooklyn, New York or Silver Lake, Los Angeles a run for their caffeinated money. Galleries dot the busy street. In the past six years, over 10,000 new residents have moved into condos in this neighborhood, which was originally built to house railroad workers. Now, the thirty-something fashionistas flit by clad in extra skinny jeans and Canada Goose outerwear.

Differentiating itself from its surroundings, the former library presents an abrupt visual difference. It’s a sturdy example of Edwardian Classicism, designed by Robert McCallum in 1908. The building has had a life in three acts—as a city-run public health center, a library, and now a theatre. Most recently it was the Beatrice Lillie Health Centre, a city run public health center. Beatrice Lillie was a Canadian-born actress who became a West End and Broadway star. Lillie was known as a great wit and brilliant parodist in her day. I cannot help but think it was somehow predestined for The Theatre Centre to call Lillie’s namesake home. Intended for public use, the building has served a cultural purpose for most of its life.

Lots of people have rich memories of The Theatre Centre. “The Theatre Centre started life as The B.A.A.N.N. Theatre Centre,” says Naomi Campbell, a twenty-six-year veteran producer from the Toronto scene. She is currently Director of Artistic Development at The Luminato Festival, Toronto’s summer festival of international performance. Campbell continues,

B.A.A.N.N. stands for Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, Autumn Leaf, AKA Performance Interface, Nightwood Theatre, and Necessary Angel. These five companies came together wanting to make a place for their own work. Together they could get space. Over the years, the companies who were involved with it changed.

Companies cycled in and then out of this loose constellation.

Process over Product

In its current iteration, The Theatre Centre focuses specifically on the development of performance and live art. For the company—and its inspiring current Artistic Director Franco Boni—the means are more important than the end result.

Over the course of Franco’s tenure, The Theatre Centre has gone from raising $20,000 annually in private funds to $300,000. In 2003, The Theatre Centre’s operating budget was roughly $300,000 compared to $900,000 in the 2014-2015 season. Their business model is based on one-third earned revenue, one-third private funding, and one-third public grants.

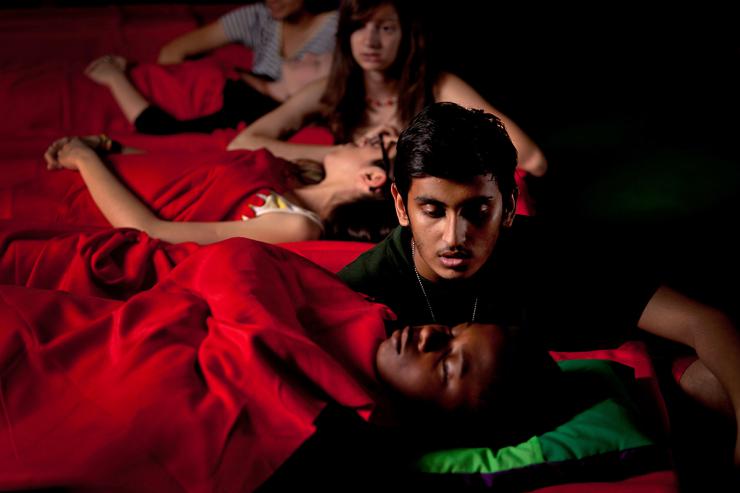

The company’s development slate is executed by way of a unique two-year residency program. Projects that come out of the program sometimes have short two or three week runs in the building, but that’s by no means a hard and fast rule. Often, this work goes on to have further development and life elsewhere. At the end of the day it is the process that Boni and company believe in most of all.

The company’s development slate is executed by way of a unique two-year residency program… Often, this work goes on to have further development and life elsewhere. At the end of the day it is the process that Boni and company believe in most of all.

“We’ve stayed true to the core mission, the development of new work,” Boni tells me while we have lunch in a creperie a few doors down. “The process is the most important thing. It’s about asking the artist: ‘What do you need to make this work? What do you need and how can we help you?’” For Boni, as well as the artists and administrators on his team, The Theatre Centre charts a course between professional practice and community engagement—it’s the height of professionalism, yet the company also looks for ways to speak directly to the community within which it resides.

Having run the company since 2003, Boni’s commitment to new performance and the community he lives in are twinned in a crucial way.

The work we do here is so raw and in such an early stage, it’s not always at its best. But it’s not about doing the best work or the best premieres. For us, it’s about the first time a piece meets an audience. Of course it’s going to be messy. And it’s going to have stuff that doesn’t work. I think part of our job is training an audience to understand the process.

The metaphor that comes to my mind is meteorological in nature, with two fronts—the audience and the experimenters—who come together like distinct weather patterns. The ensuing byproduct might be something like steam.

For us, it’s about the first time a piece meets an audience. Of course it’s going to be messy. And it’s going to have stuff that doesn’t work. I think part of our job is training an audience to understand the process.

“Franco is interested in people coming together to be together in spaces,” SummerWorks Artistic Director Michael Rubenfeld says. “He asks, ‘How is this going to bring people closer together?’”

Boni is revered in the Toronto theatre community for his quiet, calm, supportive ways. “Everyone loves Franco and feels he has mentored them, whether he feels he has mentored them or not,” chuckles Rubenfeld. In my four days on campus, I feel the company, and the building itself suffused with this mentorship-quietly-meets-chaos tone. It’s palpable.

The Theatre Centre hasn’t always been steered with such a distinctly community-minded vision. It began life as a sort of theatrical co-op. It was the 1970s after all. Like some of the best institutions, it was pure pragmatism that pulled the thing into existence. Five companies came together as a way to share space and one by one they left or burnt out, leaving only an institution called The Theatre Centre. The company has moved all over Toronto, ten or fifteen times one person tells me, like a travelling flurry of theatremakers egging each other on to make work and support one another’s work.

“The companies would determine the programming, kind of like an artist-run center where the artists made the decisions,” Boni tells me. In 1985, the model changed and the umbrella company became a sole entity along with an artistic producer who oversaw general operations—it weaned itself off the original piecemeal company model. This lasted until the mid-nineties when the board of directors hired the first artistic director, David Duclos. The idea of research and development as the core work of the company emerged.

The Residency Program

In 2003 when Boni took over from Duclos, with Associate Director Jennifer Tarver, the pair created the residency model, a hyper-successful structure for performance development. The program, simply called “Residency,” is still in effect today.

It is the center of the company’s mission and it’s given the company a real identity. “The work in Toronto is changing because of the Residency program,” Naomi Campbell tells me. “Franco has really made a point of inviting people into The Theatre Centre as their home for an extended period of time. He’s really smart about how he curates.”

When they were first devising this model, Tarver and Boni noticed “a frustration or a sense of haphazardness” Tarver remarks, “in the way emerging artists were developing new work.” Simply put, “there was the recognition that great ideas were suffering.”

Out of this came a change of ethos: “we chose to support companies who had an Idea,” Tarver enthused.

There was never any guarantee of production; we wanted to completely separate production from the two-year residency cycle. Companies would get the resources of space, a tiny bit of financial support, infrastructure, and our dramaturgical support. Within those two-years we had five showings for the artists. It was always insane! The companies we chose brushed shoulders with one another. They were witnessing ideas on the same stage. That was the key. We didn’t model it on anything, it’s just what we thought would work.

Creating the Residency program in this way was a key and conscious move away from a more playwright-centered approach. Tarver and Boni knew that the best theatre institutions have a balanced diet of creative impulses, genres, and performance styles. They wanted for The Theatre Centre to reflect this.

Tarver and Boni knew that the best theatre institutions have a balanced diet of creative impulses, genres, and performance styles. They wanted for The Theatre Centre to reflect this.

Companies like Bluemouth Inc., famous for the piece Dance Marathon, a participatory durational dance marathon, did a cycle of Residency. So too did Darren O’Donnell and Mammalian Diving Reflex, a company that creates—according to their own description—“site and social-specific performance events, theatre-based productions, gallery-based participatory installations, video products, art objects, and theoretical texts.” Through Residency, The Theatre Centre began to shift the landscape, and their own definition of “theatre” to embrace multi-genre performance.

Live Arts and Crossing Genre

Traipsing across town in the bitter cold, I visit with Tina Rasmussen, Director of Performing Arts, and Chris Reynolds, Artistic Associate, at The Harbourfront Centre, a venue akin to New York’s Brooklyn Academy of Music, or London’s Southbank Centre. I’m curious for a larger view—does such work with overlapping genre exist in the greater Toronto and Canadian scene? Where does The Theatre Centre land on that spectrum and does such work flourish once it has left The Theatre Centre?

We sit in Rasmussen’s office, surrounded by ephemera from her ceaseless travels. She offers me an Australian candy bar from her most recent trip.

[Harbourfront] is an inter-multidisciplinary arts center and we’re struggling a lot with language. ‘Inter arts,’ ‘inter disciplinary,’ ‘inter cultural,’ ‘multi disciplinary,’ ‘multi cultural;’ the term ‘live art’ whilst it has a great understanding in the UK, we in Canada are a bit behind. I would say that while we curatorially understand the term, I don’t know if there’s a burgeoning practice of live artists [here]. It’s still very much the case that a writer works in isolation, a director is hired, and then an ensemble is brought together. The question for me is: Where does performance art end and live art begin? What about the liminal space between?

Considering the artists Rasmussen is programming, it’s interesting to ponder that she and Reynolds need to constantly remind their audiences that crossing genres can be a worthwhile ticket. Just last year alone, Harbourfront in its World Stages series, had artists such as Geoff Sobelle and his piece The Object Lesson (which mixes clowning with immersive theatre); the Canadian novelist Sheila Heti’s comedy All Our Happy Days Are Stupid (literature and drama), and the Australian-Indigenous dance-theatre Marrugeku, which is working with the Belgian choreographer Koen Augustijnean (dance and theatre with multiple international influences). Speaking to Rasmussen and learning about her programming, I have a greater sense of how The Theatre Centre’s serves the Toronto ecology—it’s a place for artists to play and cross disciplines at an early stage.

“We would love to be post genre and a lot of artists would too,” Reynolds remarks.

Artists at The Theatre Centre’s Residency program can spend two years in the cycle of working and then going away, working and then going away, then they can present a show to the public with support from that process. It’s pretty remarkable.

A New Home

Back at The Theatre Centre itself, I admire how clean and bright the new building is—a perfect catalyst for creation and experimentation. This new building is a far cry from how others have described even the most recent building that housed the company. The most recent “old Theatre Centre,” known as The Great Hall, is a large Gothic-style building and former YMCA, just a few doors down the street. The theatre was in the basement, in a former gymnasium. The space was complete with an old running track that encircled the gym from above. Above the theatre was a functioning rock club. Though this performance space sounded grand, the amenities were gritty.

Luminato Festival’s Campbell cracks an impish smile when she says that the new Theatre Centre space is “a much fancier space that what we’ve had before.” She’s not exaggerating. Others have described dank and dirty dressing rooms, sweat, horrific noise bleed from the rock club, and burnt hands as a result of mistaking hot water pipes for banisters.

I point out to Campbell that she is using the word ‘we’ to describe The Theatre Centre. Many of the artists I speak to have done similarly.

I point out to Campbell that she is using the word “we” to describe The Theatre Centre. Many of the artists I speak to have done similarly.

“All the previous Theatre Centre spaces have had their charms, but this [new] place has far and away the best plumbing of any of the former spaces,” she wryly states.

Over the years, there’s always been a spirit that The Theatre Centre is a place where you can get the keys and be left overnight. That’s really crucial. There’s a trust here. If you need to just sit in the room and stare from 10pm to 6am, you can do that. That’s always been part of the beauty of it and that it hasn’t been so institutionalized.

The main entrance to the new building does not make use of the grand main steps. Instead, you walk down a gentle ramp into a bright and clean café space. The two walls that come together to form the outside perimeter of the café are entirely glass. It’s a promise and a welcome to the city and the surrounding neighborhood. “Come in, see what we are about” the room seems to be saying. The glass walls also act as their own proscenium arch. The hubbub, tumult, and creative energy on display beg to be enacted upon by those who pass by. Boni remarks,

What I love most is when I bump into somebody from the neighborhood who lives in one of the condos when they come by to pick up a brochure or to see what’s going on. I ask them if they are from the neighborhood and they say ‘I live in the condos just over there; I’ve been here already and have already seen three shows.’ It’s in that moment that I think to myself ‘Wow. It’s all worked.’

The new building features two rehearsal and performance spaces. One is called The Incubator, a big square rehearsal room with a low ramp that leads into a sunken middle. It feels like the basement engine—a space that really gets used and worked over—where artists wrestle with ideas. I can imagine an all-night artistic throw down in there.

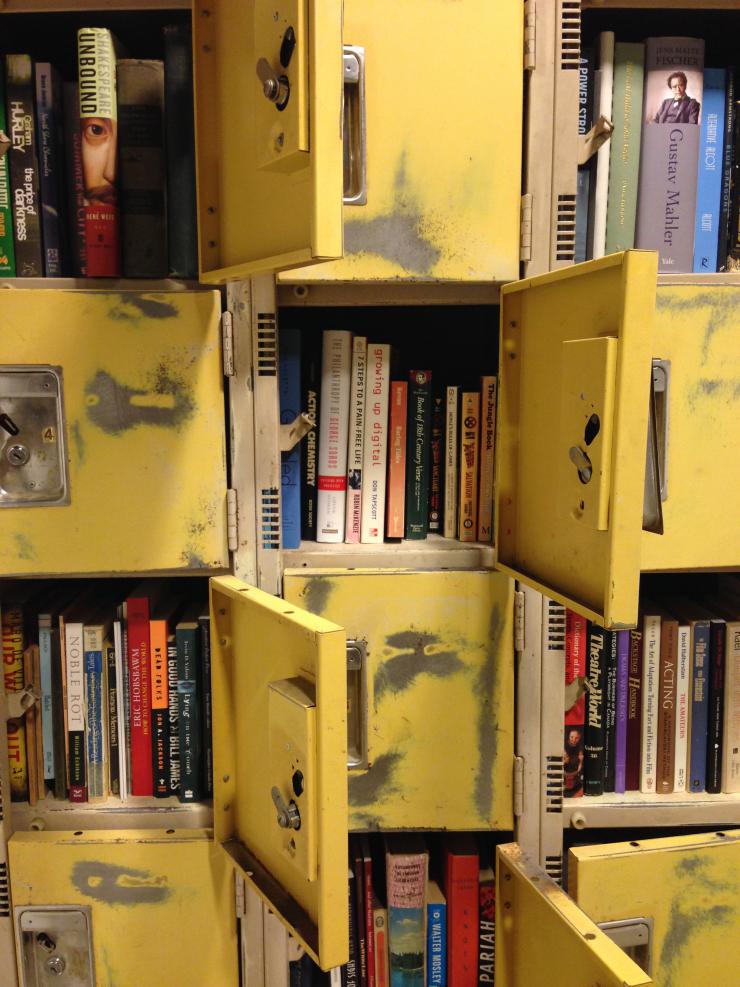

I walk past an exposed brick wall as I make my way upstairs. There is a line of paperback books; “The Lending Library” it says on a placard. Alongside this plaque is a row of photos of the building when it was a library. Women with cat–eye glasses peer out towards the camera from behind card catalogues. It’s an openhearted reference on Boni and company’s part.

On the way upstairs I pass a corner of the building where an old outside wall hits up against a new one—the outside has come in. The door opens onto a tall-ceilinged, white and raw wood-floored gallery-cum-upper lobby that adjoins the main performance space. The footprint of the building is relatively small, but one feels the clean aesthetic of the space is a perfect balance to the drumbeat of creativity.

Off the café is a narrow strip of an office where The Theatre Centre’s seven full-time employees are based. It’s a hive of activity—artists, technicians, and vendors constantly coming and going. The box office is here, too, and people in the café can see down the length of the office. There’s no visual barrier between public and private.

Off the café is a narrow strip of an office where The Theatre Centre’s seven full-time employees are based… people in the café can see down the length of the office. There’s no visual barrier between public and private.

Hospitality as Performance

Food and hospitality are a big element of The Theatre Centre’s work. Just as the café is the very first space passers by on Queen Street West see, food is deeply knit into the current iteration of the institution. The company is delineating it as a type of performance itself.

In association with The Theatre Centre, previous café collaborators BevLab created FEED, a program where local high school students are taught cooking techniques at The Theatre Centre’s kitchen. “The goal of the program is to reactivate their school cafeteria which had been completely shut down,” café and bar curator Zoe Sweet explained. “By using our kitchen the program tries to reignite the students’ own community as well.”

Food as an act of performance is an important part of this whole. Sweet speaks of monthly residencies where chefs will have free range of the kitchen. There are plans, too, to have a baker in residence, as well as curated food workshops for all to attend.

“We want to create a rehearsal hall for food people with our new café.” In future seasons, The Theatre Centre will add plantings to their green roof, and grow herbs and vegetables that will then be used in the café-made food.

Changing Landscapes

Tiana Roebuck is the member of staff charged with thinking about audiences and community as the manager of artist and community activation. Roebuck tells me about the decommissioned factory spaces turned artist studios that used to dot the multicultural neighborhood. The Theatre Center abuts Little Portugal, an area with a vast number of expat Portuguese, and just north is Beaconsfield Village, where many of the homes are heritage properties from the turn of the last century.

What I think Franco has been trying to do is to keep art in the community, when the systematic redevelopment in the neighborhood has the potential to strip that away.

To the left of The Theatre Centre, away from the boutiques is CAMH (Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health), a facility that’s been around for over one hundred years, serves as an anchor of the community, and has been under a multi-year extensive renovation of its own. Roebuck mused,

I remember coming down here to a bar called Sweaty Betty’s. CAMH hadn’t undergone any renovations yet. I sat there with my tequila and a pickle—that’s all the food they served then—and a CAMH resident wandered in. He would ask patrons to buy his drawings. And we would have a chat.

Roebuck feels that such encounters—between artists and locals from whatever mode or strata—are what The Theatre Centre is trying to hark back to. The Theatre Centre is trying to reignite this way of living in the neighborhood. She continues,

What I think Franco has been trying to do is to keep art in the community, when the systematic redevelopment in the neighborhood has the potential to strip that away. It can be uncomfortable to lose the things that made this neighborhood special. In this way, the new Theatre Centre building is one of the victories by providing a home for a diverse community of artists. It’s about reclaiming space without losing sight of the past.

It’s not just the community around The Theatre Centre that’s changing. With funding structures for the arts changing throughout the world, Canada’s cultural ecology is also in a state of flux. Current Associate Artistic Director Ravi Jain has been thinking about such change and how theatres need to change along with funding models in order to stay relevant.

“Because of the lack of resources now,” Jain tells me one morning,

I think people and theatre companies are scrambling to try and figure out how to become more relevant and diverse. How do companies attract a different sort of [audience] base into their theatres? We are in a weird time right now because people want diversity but aren’t willing to do [anything about] it. You need to create space for diversity, and people don’t seem willing to create that space.

Jain is sensing a move away from a certain Canadian politeness in the theatrical world he inhabits, and he marks this as a positive change.

Travel Exchange

Another way The Theatre Centre fuels artists to create work for the community of Queen Street West, and Canada itself, is by having artists literally leave the community. Travel is becoming a big tranche of the company’s investigative remit.

When the talented Canadian actress Tracy Wright died of cancer, her husband, writer and director Don McKellar wanted to memorialize Wright’s love of travel. Partnering with The Theatre Centre, The Tracy Wright Global Archive was created to let artists follow their bliss to wherever it was in the world they needed to go. As described by The Theatre Centre, “the project challenges artists to explore a burning question and create a new work by engaging deeply with communities and locations across the globe.”

The First Nations theatremaker Jani Lauzon was in the inaugural group of artists who took part in this program a year ago. Like the Residency program itself, “The Theatre Centre and the Tracy Wright Global Archive let me come to a project with no boundaries,” Lauzon remembers. “I chose to go to a place called The Giant Rock in the Mojave Desert. I went down and spent some time there and did research and I’m now creating a piece.”

Lauzon is a storyteller, actress, and puppeteer. She’s an elder stateswoman of the Canadian art world. I ask her about what it is like to be a senior artist at The Theatre Centre, long a place that incubates emerging artists.

The interesting thing about being a veteran artist in all disciplines is that you get to a certain point, and it becomes a challenge to make work and to grow. Youth and innovation have always been a focus of The Theatre Centre. Franco understands the value of inclusivity—of age, gender, and cultural diversity. As a Native Artist I feel lucky that way.

A Home for All

The Canadian model of theatremaking is vastly different from the American model. It is mostly entirely based upon state funding from granting bodies—more akin to other Commonwealth countries like the UK and Australia. Interestingly, The Theatre Centre is home to a number of artists who have spent time in the harsher funding climes of the US, but who now work in Toronto.

Jess Dobkin has lived in Toronto for twelve years. She identifies as “a performance artist who likes being at The Theatre Centre because as a performance artist she is ‘in the cracks of things.’” Her art is not text based.

Originally from New York, when Dobkin first got to Toronto she did a lot of work at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, a company that focuses on work by queer artists and work with queer themes. Dobkin points out that as an artist currently in the Residency cycle, her relationship to the company is about as old as the company’s new home—just over one year.

The Theatre Centre asks, ‘What does the work need and how can we facilitate that?’ That was so exciting to me because in Canada, so much of the work that gets done is determined by grants and grant cycles. That system has its pluses and minuses of course. In New York, I find that you make the project because you have to make it! You find a way of doing it. Here I find that sometimes artists won’t make the work if they don’t get the grant. Sometimes the work suffers because of this funding model, but it’s tricky. Absolutely artists should be receiving this funding, but I kind of miss the other spirit too. …It’s so different being an artist here. I receive funding for pieces where I’m having people taste women’s breast milk. That would never happen in the US. I can send the Toronto Arts Council images of me being fisted as Kermit the Frog and they’re like ‘Alright.’ I feel like there is support here to make work. Having come from the US, I don’t take that for granted.

Dobkin is palpably enthused about her time ingesting everything the company has to offer. She speaks of the Residency program in the same open ways that the former Associate Director Jennifer Tarver does.

I have three work periods per year. My first was in December 2013. I gave myself the task of not knowing what I was doing; just brainstorming and generating, no crafting. It was hard for me because I am so used to working on a timeframe and towards production.

For Dobkin it’s a way of consciously slowing down the process. Like Ravi Jain and Naomi Campbell noted, the company infuses the feeling of total freedom in all its artists. Whether or not the artists have the literal keys to the building, it’s clear that Boni figuratively leaves the door unlatched.

Michael Wheeler, Artistic Director of Praxis Theatre, has also spent time in the US. He received his MFA in Acting from the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge. After spending time in New York upon graduation he returned to Toronto. Wheeler is tall, sharp-eyed, and describes Residency’s difference in no uncertain terms.

“This theatre has abandoned the old model,” he bluntly declares.

The way they’ve taken up the incubation model and the artists’ residency model is totally unique. They really don’t feel like they own the work they create. …I think what a lot of the other Toronto theatres have struggled with is that they put a bit of money into a project and they want to develop it into something that’s just their own thing. It often doesn’t work as a development model.

It’s not just the artists themselves who feel the change in governmental arts funding, of course. The venues do as well. Wheeler continues: “This [new Theatre Centre building] is a miracle. We’ve gone through four years of Rob Ford being our Mayor here, the provincial political situation has not been great for the past decade,” Wheeler reflects, though the conservative Federal government was also a great barrier. “Yet somehow the weird, experimental, political theatre company got built with public money in a heritage institution. That it happened in this political era and climate is a magic trick that’s hard to comprehend.”

Wheeler and I sit in the clean, well-lit, new theatre foyer. As the cold winter night darkens around us he looks out of the large Victorian window. Three or four buildings down Queen Street West—beyond a graffiti sprayed wall that feels like the old neighborhood this area has outgrown—the most recent old home of The Theatre Centre sits.

… housed in this heritage building, something is going to have to be here forever. It’s permanent… the hope is that it will become a genuine hub for the community—and not just the arts community.

Wheeler reflects on the old building’s history as a YMCA around the turn of the twentieth century. He tells me of the famous Canadian First Nations long-distance runner, Tom Longboat—winner of the 1907 Boston Marathon—who used the running track in the great hall to train. After WWII, many Jewish immigrants fled Nazi Germany, came to Toronto, and lived in tiny apartments above Longboat’s running track. It has been a cultural and community center for more than one hundred years.

“You can feel the history in that old building,” he remarks. “It [was] a real historical, well used, lived-in building.”

The new building hasn’t lost sight of history. I ask Wheeler to speculate about what’s next:

I think a lot of crazy things are going to happen here in the future. What makes me so hopeful is now that The Theatre Centre is housed in this heritage building, something is going to have to be here forever. It’s permanent. I think this building will always be about process and creation; the hope is that it will become a genuine hub for the community—and not just the arts community. That’s the battle and the goal.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

“The process” that any art undergoes is perhaps the most important part of the art. It is the development, the thoughts, the hard-work, the creativeness, the thrown-out bits that just didn’t work. I had a professor write in his syllabus, “The technique is process-oriented rather than product-oriented and in that sense is not about getting anywhere, but learning how to go.” This was one of the most profound things I have ever read, because it opened my eyes. Every piece of art is interpreted differently by every human, based on their life experiences and how they view the world. The process is the part that we artists take pride in when all is said and done.