Teenage Girls on Stage

Young Women Who Do Things

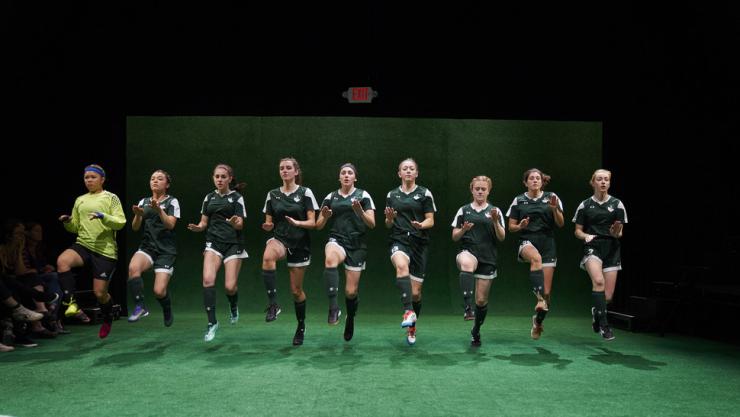

Oh to experience the world of a teenage girl in ninety minutes (disclosure: I wish my teenage years had only lasted ninety minutes). When I sat in the Duke on 42nd in New York City, next to the green, green Astroturf and girls in shorts dribbling soccer balls, I found myself back at sixteen—no more acne or braces, but with a distinct sense of longing for a time that felt both limitless and impossibly constricting. Sarah DeLappe’s The Wolves has—naturally—excited audiences from Vassar to Playwrights Realm to, now, Lincoln Center. And it deserves it: The Wolves is a beautiful, funny, weird, lovely play and I cried when I first read it, I cried when I saw it Off-Broadway, and I’ll cry when I see it at Lincoln Center.

But something else about The Wolves struck me as I first read it: it was about girls. Girls! Ever since I’d cracked open a teenage monologue book when I was auditioning for the school play, I’ve found it impossible to find plays about girls. Sure, you have your myriad Little Women adaptations and I guess Annie is a tween, but where are the plays about teenage girls?

So I took to Facebook. I posed the question to my friends, asking them to shout out as many plays about teenage girls by women as they could think of. The Wolves was joined by Dry Land, last season’s favorite about two friends on a swim team, featuring a medically induced abortion.

But otherwise? A lot of head-scratching. (Granted, these are produced plays I’m counting. Unproduced plays—and unrepresented plays—took up a wide swath of the list at the end of this essay.)

My Kilroys List Jr. was very short—just thirty-one plays total. And, rest assured, I surround myself with people who enjoy sitting at home with plays as a way of life. If anyone could compile this list, it was the 1,069 dramaturgy nerds I call my Facebook friends.

…teenage girls are some of the most ardent theatregoers around. So why don’t we have more stories about them? And why, oh why, are more theatres not choosing to put teenage women at the center of their stories?

Now, as an agent and dramaturg, I see this question as a matter of great importance to our theatrical ecosystem. If we take our New Play Map (thanks, HowlRound!), how much of it will contain plays by women about young women? The Lilly Awards’ the Count tells us that 22 percent of the plays on stage would be written by women. And the Kilroys would tell you that, despite a huge amount of female writers graduating from prestigious grad schools and snagging agents, they still can release an extensive list of unproduced plays. And, in looking at catalogues for this season on Off-Broadway and on Broadway, I could only scrounge up two (brilliant, thrilling) plays by women about young women: The African Mean Girls Play by Jocelyn Bioh and… The Wolves. (Honorable mention to Michael Crowley’s The Rape of the Sabine Women, by Grace B. Matthias, which is, perhaps, one of the most sympathetic portrayals of a young woman by a man that I’ve ever read.)

What gives? According to the Broadway League’s 2015 study, over 1.45 million teenagers saw a Broadway show in the 2014–15 season, and 67 percent of theatregoers were female. (Their average age? Forty-four, just old enough to be raising a teen.) That’s not counting Off-Broadway, LORT theatres, college conservatories, high schools, your friend’s backyard, community theatre…. If my memory serves me and my intern applications keep coming up overwhelmingly female, I would argue that teenage girls are some of the most ardent theatregoers around. So why don’t we have more stories about them? And why, oh why, are more theatres not choosing to put teenage women at the center of their stories following the success of The Wolves?

It’s not that teenage girls haven’t been on stage, per se. After all, many male coming-of-age stories feature a young woman prominently (think Kenneth Lonergan’s This Is Our Youth or Anna Jordan’s Yen), as do Shakespearean classics like Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet. But rarely do we see women at the center of their own stories rather than as objects of desire—or victims of violence (one could write a whole series on bodily harm done to young girls on stage and our culture’s fascination with sexual violence).

But to focus on the inner lives of teenage girls—to portray them as subject rather than object—is something that seems to have evaded us. While the Judy Blumes of the novelistic world were born, something stayed dormant in the theatre community. “Agency is something I want to see more of in plays about women,” Playwrights Horizons literary manager Sarah Lunnie told me over drinks as we pondered my list. I wanted it too: women who do things, not have things done to them. Did this seem too much to ask?

Rarely do we see women at the center of their own stories rather than as objects of desire—or victims of violence.

Maybe it’s the idea that only certain people can inhabit the world of drama. After all, before Willy Loman, we weren’t much interested in the everyman—let alone the everywoman. Theatre has often been reserved for the rich and proud and high in stature: if the 2016 election shows us anything, it’s that these seats aren’t open to even the most privileged of women. Indeed, when looking at the plays that do pass the teenage-girls test, it’s worth noting that most take place in the suburban, primary white, and decidedly upper-middle-class sphere. Is this surprising considering the high price tag of most MFA programs and the demographic makeup of most audiences? Well, no. But it is worth saying that male characters have their Sam Hunters and David Lindsay-Abaires, writers who focus on lower-income male characters. Female teens seem to have… no one. Aside from Kirsten Greenidge’s Milk Like Sugar, the majority of the list I compiled portrayed women in positions of relative financial security. And, as in the rest of stories represented on stage, the list was overwhelmingly white—Milk Like Sugar, BFE by Julia Cho, and Our Lady of Kibeho by Katori Hall were the only plays by women of color. None of the plays on the list were written by trans women.

To be a teenage girl is to be blisteringly vulnerable—to talk about periods, first kisses, crushes, sexual awakenings, fantasies, dying your hair in the sink, going shopping at Forever 21, crashing your mom’s car. Teenage girls are difficult and intense and awkward and unapologetically female. And perhaps, I wonder, that’s why we won’t put these stories onstage. After all, male theatre critics are slow to take to plays that play girlish. “I didn’t care for the show the first time I saw it. Female empowerment is fine for daytime television, but it’s flesh-crawling in a musical,” wrote Michael Riedel of teen-centric The Color Purple’s revival in 2015.

And the darkest thought remains: there’s much cause to think that our society may just have a seething hatred of teenage girls—point-blank. There are the capital “M” Misogynistic things: the Steubenville rape case; cuts in funding for the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, which works with organizations across the United States to implement evidence-based, proven programming; the erasure of Title IX protections by the Trump administration; a lack of sex education with a focus on issues of consent and female pleasure. There are the slyer, more creakingly sexist things: internalized misogyny; the way we dismiss young women’s emotions as irrational or dishonest or dangerous; how we tell girls to hide their tampons in their bags, their opinions in their throats, and their anger in their stomachs.

But, in my more optimistic moments, I think we do not have these plays because we are only just beginning. I think the most optimistic way to look is forward—and I think we must do so to create change. We will know trans girls and undocumented girls and girls who are not skinny and girls who are not “nice” and girls who like girls and girls who don’t particularly like anyone and girls who are unlikable and gross and mean and horrible.

On good days, I am excited for this future season of bustling teenage brilliance to come. On bad days, I wonder if we are too late for someone—if we’ve left too many young girls out in the cold and exiled them out of the theatre. I don’t want to think of that scenario, but think about it we must if we’re going to take full responsibility for our power as gatekeepers.

For me, perhaps the most exciting part of The Wolves was when the lights came up on a jumble of female bodies—different shapes, queer bodies, Brown bodies, athletic bodies, bodies that looked like my friends’ bodies, and bodies that looked like my body. It was exhilarating to see myself at sixteen on stage. I hope to have this experience again soon—one I wish I had known when I was a teenage girl.

LIST*

- The Wolves by Sarah DeLappe

- Milk Like Sugar by Kirsten Greenidge

- Dry Land by Ruby Rae Spiegel

- I’ll Never Love Again by Clare Barron

- Chimichangas and Zoloft by Fernanda Coppel

- Our Lady of Kibeho by Katori Hall

- How to Make Friends and Then Kill Them by Halley Feiffer

- All the Roads Home by Jen Silverman

- Dance Nation by Clare Barron

- BFE by Julia Cho

- tender of you too by Anya Richkind

- The Children’s Hour by Lillian Hellman

- Horse Girls by Jenny Rachel Weiner

- Little One by Hannah Moscovitch

- Scratch by Charlotte Corbeil-Coleman

- I Am For You by Mieko Ouchi

- Scorch by Stacey Gregg

- Joan by Lucy Skilbeck

- SHE by Renée Darline Roden

- How I Learned to Drive by Paula Vogel

- Jailbait by Deirdre O’Connor

- School Girls; Or, The African Mean Girls Play by Jocelyn Bioh

- Geek! by Crystal Skillman

- Chill by Eleanor Burgess

- Honors Students by Mariah MacCarthy

- I Know What Boys Want by Penny Jackson

- Fat Kids on Fire by Bekah Brunstetter

- The Tall Girls by Meg Miroshnik

- Giant Slalom by Jess Honovich

- That Poor Girl and How He Killed Her by Jen Silverman

- The Burials by Caitlin Parrish

*Note: This is a crowdsourced list and certainly not comprehensive.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I’m a high school theatre teacher at a historically black high school in Louisiana. Thank you for this article and this list. I plan on picking up copies of some of these scripts for my school’s script library once I’ve read them, and I hope to incorporate some of these shows into my season selection.

Hello! I love this article - brava, Helen!

I am honored to be included on the list (my name is Anya Richkind). I was wondering, could the title be changed to "tender of you too"? "Chapped Lips" was the previous title for the same play but it's now "tender of you too". Thanks so much!

We've made that change. Thank you!

Thank you!

I wish Schultz had taken the time to annotate the list -- subgenres, dates, etc.

Great article! I would like to add:

Girls Like That by Evan Placey

Pronoun by Evan Placey

Girl. by Megan Mostyn-Brown

Thanks for this! I'd like to add Yard Gal by Rebecca Prichard,

I have two plays about teenage girls "Because of Beth" about two sisters (one teen, one early 20's) dealing with their mother's death and "Daughter", a play about a teenager who is contacted by her biological mother over Facebook for the first time. http://www.elanagartner.com

Thanks for the article - What Every Girl Should Know, by Monica Byrne should be on this list!

Cuttin' It by Charlene James. https://www.theguardian.com...

I'm always writing about teenage girls. They figure in some way in nearly all of my work but specifically Tar Beach takes place in 1977 Queens about three teenage girls during the New York City Blackout. Premiered at Luna Stage and mentioned in the first Kilroys list and available on New Play Exchange! Great article. I think the plays are out there, but artistic directors, theaters dont know what to do with them. Also would like to add Molly Rice' s amazing theater with dance piece Dont Stop.

Canadians to add to the list: "Girls, Girls, Girls" by Greg MacArthur (although, in my opinion, very clear it's written by a man) and "Gracie" or "Shape of a Girl" both written by Joan MacLeod.

Great article, by the way!!

Breathe, Boom by Kia Corthron

There are so many more. Playscripts and YouthPLAYS have many such plays. Adding my By Candlelight (Bonderman winner, Aurand Harris winner) published by Playscripts about healing after 9/11; Antigone in Munich: the Story of Sophie Scholl (Playwrights in our Schools grant) which I am keeping close for now as it has a few productions coming up and I can make it better.

I'd like to add my plays HEARTLAND and MI CORAZON to the list. Check them our on the New Play Exchange -- Lojo Simon

Tight End by Rachel Bykowski

i love this article and i really appreciate this list, but would love to add that there are hundreds of plays written about teenage girls BY teenage girls and are filled with all the feelings, stories, challenges, dramas, relationships and experiences that girls actually are living today. teenage girls are often the best scribes of their own realities. check out the work of www.vibetheater.org, www.girlbeheard.org and for plays written in collaboration with teen girls - http://theartseffectnyc.com...

BFF by Anna Ziegler

Thank you for this article! As a director I love working on plays that explore teens but there are so few good ones especially centering around young women. You've really illuminated for me some of what I hadn't been able to put into words about why this topic is so important to me.

I can't wait to read the plays you've listed here! And would love to add a couple more for others who are looking. The Firebirds Take the Field by Lynn Rosen and Eat your Heart Out by Courtney Baron have both been produced in recent years at Rivendell Theatre in Chicago (an amazing company that focuses on plays by and/or about women) and FML: How Carson McCullers Saved my Life by Sarah Gubbins which was part of Steppenwolf for Young Audiences a few years ago.

All The Fine Boys by Erica Schmidt, which was produced by The New Group last year!

GREAT article. I'd suggest Catherine Trieschmann's "Crooked," Jiehae Park's "Peerless," and perhaps "Tales of a Fourth Grade Lesbo" by Gina Young. Hmm, are any of the versions of "The Diary of Anne Frank" by women? And I can't remember how old the characters are in Young Jean Lee's "Song of the Dragons Flying to Heaven"... There's also new devised theatre piece prominently featuring female teenagers in several parts done in Boston by Off The Grid Theatre called "The Weird," a collaboration of four playwrights (three are women: Obehi Janice, Lilah Rose Kaplan, and Kirsten Greenidge).

Don't think I've see it mentioned in the comments but Lauren Yee's Hookman should definitely be on this list. And SpaceGirl by Moira Harris. Also I and You by Lauren Gunderson.

Love this article, and this list-- and I'd love to add my own play, Waving Goodbye which premiered at Steppenwolf Theatre in co-production with Naked Eye Theatre, with a 17 year old girl in the lead. (Published by Playscripts, Inc).

By Arlene Hutton: Letters to Sala (DPS) Kissed the Girls and Made Them Cry (Playscripts) and As It Is In Heaven (DPS). One problem I have is that professional theatres think plays about teens are for schools. A theatre in a major city said "we only do plays about adults" and then put Romeo & Juliet in their season.

Thank you Helen - it is great that you are compiling a list! It's a great article, even if I disagree with you on Michael Crowley's portrayal of Grace B. Matthias.

I also adapted Antigone for 9 women with a 15 year old Antigone and her older sister Ismene is the title character - it's called Antigone's Sister and deals with internal oppression and Ismene's regret over not helping Antigone. But I gave up ever having that produced decades ago.

How To Destroy An American Girl Doll + What's Wrong With You by Jan Rosenberg

I wrote Perfect Women in the 90s and it won a Jane Chambers - the protagonist is a 12 year old girl. The Washington Post said I really got teenagers. . . All Out Arts Inc produced it in NYC and it had a few small productions elsewhere and then crickets.

Whorticulture, having a 1 Night Stand at Dixon Place this Friday (10/20/17) at 730pm, is about girls in a very big way! With an ensemble of 3, including an African American, an Asian American and a white girl, it is very much about girls and our experience as girls was shortlisted by Cutting Ball and Owl and Cat this year.

Also shortlisted at Cutting Ball, Abraham's Daughters features 4 women and 1 man, 2 of those women are adolescent girls. Tamar (The Two-Gated City) another play of mine is an adaptation of 2 rape culture stories from the Bible for 3 women, 2 of whom are adolescent. Also shortlisted at Cutting Ball -- Why Birds Fly is a 2-hander for 2 women, including 1 adolescent. . . Now I am starting to wonder if the reason my work never gets produced is for the very reasons cited in this article! So maybe things will shift soon, because suddenly maybe people are ready to hear teenage girls.

Crooked by Catherine Trieschmann and while it's not exclusively girls, it certainly has a young woman at its center---End Days by Deborah Zoe Laufer. Leaves by Lucy Caldwell. Language of Angels and Aloha Say All the Pretty Girls, as well as Good Kids, all by Naomi Iizuka. Baltimore by Kirsten Greenidge features, specifically, a variety of young women of color. (Can you tell I teach high school theater?)

Wonderful piece! Here are some other plays I thought could possibly be added to the list, they don't focus primarily on teenage girls but teenage girls are in them: Mirror Mirror by Sarah Treem, That Face by Polly Stenham, 100 Saints You Should Know by Kate Fodor, Circle Mirror Transformation by Annie Baker, And I And Silence + The Trestle At Pope Lick Creek by Naomi Wallace.

This is an important issue. If I may, I'd like to mention my play, CRYSTAL SPRINGS. It is about teen girls and cyber-bullying and was produced in San Francisco and London. It features three teen girl roles and three roles for older women.

Does Eve Ensler's "Emotional Creature" count?

How about:

I and You, by Lauren Gunderson (which is produced a lot!)

Good Kids, by Naomi Iizuka

Kissed the Girls and Made Them Cry, by Arlene Hutton

There is also good work being done on high school stages by female playwrights featuring teenage girls.

I'm thinking of Dark Road, by Laura Lundgren Smith and Viral by Maria McConville.

Thank you so much Helen for including I KNOW WHAT BOYS WANT. My other teenage girls play is SAFE. You can purchase I KNOW WHAT BOYS WANT on Amazon.

Great article. Slight correction: it’s HONORS STUDENTS (plural) by Mariah MacCarthy (not “Mc”).

Thank you! This has been corrected.

Thanks for this great piece, Helen. I'm curious whether this is more an issue of gender or age. How many produced plays about teen boys are out there? I can immediately think of several, and I suspect the number is far higher than plays about girls.

When looking at the current season, you missed two upcoming plays (by women, about or featuring teen girls) at Playwrights Horizons: Dance Nation by Clare Barron ( on your list) and This Flat Earth by Lindsey Ferrentino.

Thanks for the article! Add Habitat by Judith Thompson!

Great article. Glad that someone is writing about this. Someone should tell the writer that Qui Nguyen is not a woman though.

Thank you! We've removed Qui from the list.