Queer Climate Performance Art in the Most Unlikely Places

Twice a year, I look forward to putting together this Theatre in the Age of Climate Change series. The depth and breadth of work being done at this intersection reminds me that though there are plenty of reasons to despair (here’s one of them), there are also countless people determined to keep the planet habitable, and all of its creatures alive and thriving. My friend Peterson Toscano is one of those agents of change and he is a master at engaging people around climate change in a way that is funny and completely disarming. —Chantal Bilodeau

“What is your presentation about?” Clara asks. Like most undergraduate science majors in this lecture hall, Clara has never seen a one-person performance art piece. Without stage lights or a sound system, I set up in the multi-purpose room. A console the size of a small car serves as lectern. Two hundred students sit in tiered seating above me. I tell myself, “It is just like an Amphitheater in Ancient Greece.”

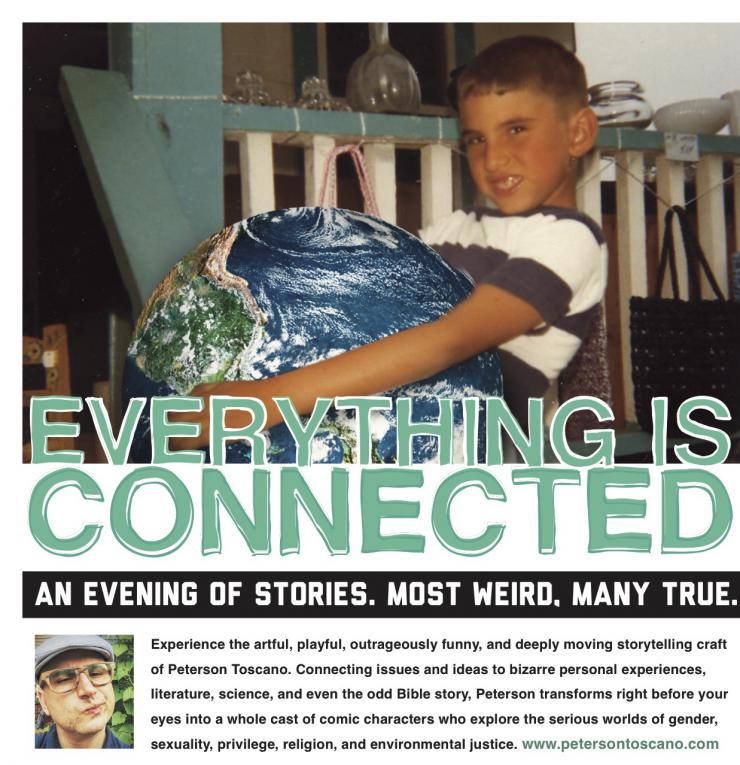

I tell her, “Everything is Connected is a one-person play. Don’t take notes; just enjoy.” She must be thinking, “I could be doing real work right now.” A professor introduces me, “Peterson is a quirky queer Quaker, a playwright, actor, performance artist, Bible scholar, LGBTQ rights activist, and host of Citizens’ Climate Radio.” A handful of students applaud. I begin.

I seek to use my skills as a playwright and actor to take on LGBTQ issues, justice, privilege, and climate change while revealing the interconnectedness of these issues.

“What you are about to see is a performance lecture in three acts. These acts may seem unconnected. l will talk as myself and also perform in character.” I don’t tell them this type of presentation rose out of the tensions I feel being an artist, an activist, and an academic. These roles pull at each other, competing to take a prominent place. My shows attempt to give them each equal pull, like the cords that enable a tent to hold its shape.

I seek to use my skills as a playwright and actor to take on LGBTQ issues, justice, privilege, and climate change while revealing the interconnectedness of these issues. I also throw in a Bible story. Within these different frames, I repeat core concepts knowing audience members will begin to see patterns emerge. In first performing my own very personal story, then an ancient Bible story, and finally the unfolding global story of climate change, I lead them to a synthesis of abstract ideas as outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning.

Act One

The first act of Everything is Connected includes me talking about my weird coming out experience coupled with a scene from my one-person play Doin’ Time in the Homo No Mo Halfway House. The play comically exposes the dangerous world of gay conversion therapy—programs promising to “cure” LGBTQ people. As someone who survived seventeen years of this before coming out as gay, I want to highlight both the foolishness and the destructiveness of these “straight camps.”

The main character, Chad, a campy gay man who cannot tamp down his fem side, addresses the audience as if they just arrived for a tour of the house. This relationship heightens the audience’s experience; Chad addresses them as if they are totally on-board with the misguided facility.

Act Two

Something similar happens in Act Two where I talk about discrimination within the LGBTQ community—racism, sexism, and transphobia. I perform a scene from Transfigurations—Transgressing Gender in the Bible about Joseph and his famous dream coat; I suggest it might actually be a princess dress. I narrate the scene as Joseph’s butch, gender-normative Uncle Esau. Scornful of Joseph, he never once makes eye contact with the audience until the final line. There is a pause and deep breath as Esau lifts his head and in a husky whisper admits, “He saved us all.”

I imagine Clara is thinking, “What on earth does any of this have to do with climate change?” I am performing stories about outsiders rejected—a white gay man who loses male privilege in an Evangelical church and brothers who assault and exile their gender non-conforming sibling. I reference the HIV/AIDS crisis, Ancient Egypt, and my own working class Italian-American family. I’m throwing out threads and asking, “Aren’t we all in the same boat together?” I’m setting Clara up for Tony Buffusio in Act Three who weaves it all together.

Act Three

Tony, a working-class, bisexual, Italian-American from New York City, pokes fun at polar bears, explaining coffee is also an endangered species. He jokes how he came out bisexual and vegan at the same time; his family struggles more with his diet than his sexual orientation.

Talking about queer responses to climate change, Tony revisits the Joseph story as a climate narrative, reveals how early responses to the HIV/AIDS crisis serve as a model for climate advocates today, and stresses climate change is about justice and human rights, “We’re all in the same boat together—just not on the same deck.”

Then in an explosion of emotion ranging from rage to frustration to fear, Tony demonstrates what many people feel today. He next admits he’s been hearing voices from people in the future. “You don’t expect they have anything nice to say to us. But I’m confused by what they’re saying. They’re telling us,” and he looks out an audience member, “Thank you!’” He looks at another, “Thank you,” and another, “Thank you for everything you did for us!” He scrunches up his face puzzled, and ends the show, “So I’m thinking, what the hell are we about to do that they’re going to thank us for it?”

In a proper theatre, there would be a black out. Exit Tony. In this multipurpose room, I slip behind the lectern and say, “We have time for questions.” Deep, thoughtful questions emerge. They are hungry for solutions, to discover their role.

Unlike a traditional play with multiple actors interacting while the audience observes, the one-person comedy turns the audience into a character. We speak directly to them, casting them in roles.

For fifteen years, I have been doing theatre for clients in venues that usually never hosted a queer theatrical production. These include the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, Hartford City Social Workers, Offices of Sustainability at Penn State, University of South Carolina, and Villanova, Haverford College’s Office of Religious Life, Boston Public Schools, Britains’ National Health Service, the Church of Sweden, the Norwegian Christian Student Movement, the Lambeth Conference, Vanderbilt School of Religion, Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia Theological Seminary, and a Mennonite Church in Pittsburgh.

The solo stage work of Whoopi Goldberg, John Leguizamo, and Lily Tomlin taught me marginalized people can use comic storytelling and character acting to communicate personal and political messages. These comic actors shape-shifted and embodied multiple personalities as they developed immediate and intimate relationships with their audiences. Unlike a traditional play with multiple actors interacting while the audience observes, the one-person comedy turns the audience into a character. We speak directly to them, casting them in roles.

Since I take on hot-topic issues in front of diverse audiences, I always expect someone to leave offended in a huff or to start an argument during the Q&A. Climate Change presentations can overwhelm audiences or they can become defensive. Instead after my shows people stick around. I hear laughing and chatting. I see people connecting with each other. Some approach me just to thank me. Others want to tell me their stories. There is a lightness in the audience as they disperse.

As I pack up, Clara smiles. “I get it now, and you gave me so much to think about!”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Peterson, this sounds amazing! I hope to see it sometime soon. I am keeping your contact information for future opportunities. So glad we crossed paths at Eastern Mennonite University.

Heidi! Great to see your name again. I remember fondly the performance at EMU. It was quite courageous of the school to step up and host the presentation on gender non-conforming Bible characters. I was so grateful for the discussion afterwards, but I especially enjoyed the class with your students. Hope to see you one day soon.

This is so great. I’m very glad I learnt about this work and hope I get to see it!

Thanks! I will present this show at universities around the USA this spring.