Looking for “Lesbians” in God of Vengeance and Indecent

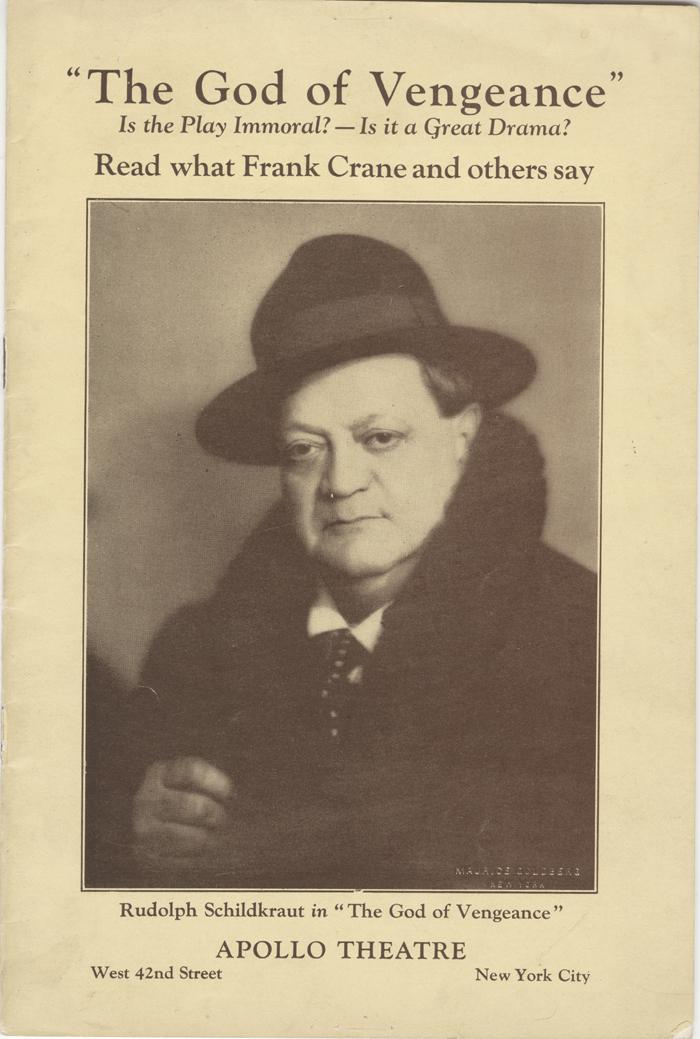

Two women, drenched from the rain, kiss passionately on the Broadway stage. This may sound like a cut scene from Fun Home, but in fact, this took place at Broadway’s Apollo Theater in late 1922, where the English translation of Sholem Asch’s play God of Vengeance was making its Broadway debut after a run at the downtown Provincetown Playhouse.

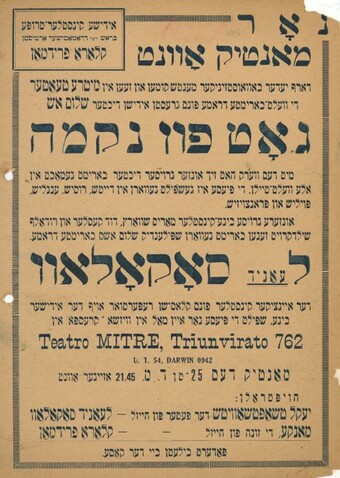

First staged in Yiddish in 1907 around the world, including the Thalia Theater down in the Bowery, Got fun nekome, as the play was known in Yiddish, is about patriarch Yankl Tshaptshovitsh, a brothel owner, who tries to redeem his life’s questionable actions by marrying off his daughter Rivkele to a respectable young man. Unbeknownst to Yankl, though, is the fact that Rivkele, who is supposedly pure and innocent, has been cavorting with the prostitutes who live underneath her family’s home. And if that were not enough, she has fallen in love with one of the prostitutes, a woman named Manke. Boldly going where no other play had yet ventured in terms of female sexual expression, Manke and Rivkele’s relationship builds to a climax in the play’s now (in)famous second-act love scene in which the two passionately brush each other’s hair, kiss on stage, and talk of sleeping in the same bed. As rare as it still is to see female same-sex relationships on stage today, it was virtually unheard of in 1922, let alone 1907.

Can something be 'immoral' if we don’t have a word for it? Did the audiences who saw two women kissing on stage in 1907—or in 1922, for that matter—know what they were seeing if they didn’t have the language for it?

Without the context of a thriving LGBTQ world to ground the play, it’s not surprising that God of Vengeance raised more than a few eyeballs. The play was found to be so scandalous that in March 1923, under New York Penal Law 1140A, the cast and producers were found guilty of performing “immoral” drama on the Broadway stage. This would only happen one other time in US theatrical history, in 1927, when Mae West was also found guilty of presenting immoral work with her play Sex. While the God of Vengeance case was later overturned on appeal, there was the general sense that there was something “off” and morally wrong about a play that involved prostitutes, corrupt Jews, and a same-sex love relationship. The appearance of God of Vengeance in 1922 was no small deal; it brought up a number of issues that were beginning to percolate in the zeitgeist around Jewish ethnicity and queer sexuality. In 1924, just a year after the court case, the immigration of Jews and other “less desirable” minorities to the US would be strictly curtailed under the Johnson-Reed Act, a restriction that seemed to stem from fears about the questionable morals of Jews as depicted in works like God of Vengeance. And in terms of sexuality, Asch’s play not only predates the publication of the groundbreaking lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall in 1928, but it emerges at a time in which theories around homosexuality, such as those articulated by Freud in 1905, were hardly mainstream.

The question remains: why precisely was the play seen as immoral? Was it because two women kissed on stage? Was it because Yankl ran a brothel? Truly, it was hard to say. The 1923 court case was actually rather vague about what it was that was so offensive. And while the play had a smoother run in Yiddish when it first premiered in the States in 1907, it did come under attack from a number of Yiddish newspapers that had a number of choice words for the play including that it was, full of “shlekhts” (terribleness) and “shmuts” (filth) and that it was “oysgelasene” (indecent).

It’s this word, “indecent,” that contemporary American playwright Paula Vogel chose for her 2015 play of the same name. An imaginative dramatic history of the play’s origins from inception through the 1923 trial and then beyond, Vogel recovers this play for modern-day audiences—despite its healthy performance history in multiple languages including four English translations, it’s not very well known outside of Yiddish circles.

For contemporary audiences, the aspect of the play that most startles is its bold on-stage same-sex relationship between Manke and Rivkele. For Paula Vogel, an out lesbian and Jewish playwright, Indecent enabled her to recover a seemingly lost moment of queer Jewish theatrical history. But despite what occurs on stage in Asch’s play, an important question remains: are Rivkele and Manke actually “lesbians”?

In a post-Stonewall world, it might make sense to read the women as such, and yet, the history of God of Vengeance and of Yiddish language itself proves much more complex and—at least to me—more fascinating. In Vogel’s reimaging of the play’s history, including a number of scenes that take place in Yiddish (although performed in English), her characters talk about the “lesbians” in Asch’s drama. This seems logical except for one problem: Yiddish doesn’t have a word for “lesbian,” at least not in 1907. Only many years later will Yiddish take on the cognate “lesbianke.” For that matter, the word “lesbian” wasn’t even in common parlance in English at the time; rather, if any language around sexual identity was invoked it was the concept of the “sexual invert”: the mannish woman who preyed on her more feminine victim. This issue over diction might seem like a small and even pedantic observation, but in fact, the struggle over language in God of Vengeance and the question of what we call a same-sex relationship between two women in Yiddish in 1907 is what the play is really all about. Can something be “immoral” if we don’t have a word for it? Did the audiences who saw two women kissing on stage in 1907—or in 1922, for that matter—know what they were seeing if they didn’t have the language for it?

The history of the language surrounding homosexuality from the nineteenth century on was wrapped up in this dance with morality. The creation of the word “homosexual” in 1868 by sex-law reformer Karl-Maria Kertbeny might have been a way to finally name certain sexual acts or behaviors, but in naming them, it also unfortunately enabled these same acts to be policed, legislated against, and deemed “immoral.” The Yiddish- and English-speaking audiences of God of Vengeance struggled with the question of just what to make of the relationship between Manke and Rivkele precisely because mainstream society at the time lacked our contemporary understanding and vocabulary of what would now be known as “lesbianism.” When the play premiered in Yiddish in 1907, the Yiddish reviews at the time had no language to describe the relationship between the women; the handful of condemnation that was exhibited towards the play was about the brothel and prostitution, not about Manke and Rivkele’s relationship. In fact, the majority of the reviewers in Yiddish even felt that the second-act love scene contained a great deal of poetic and lyrical writing and was the play’s greatest asset.

While the cast of the 1922 production was found guilty under New York’s new morality and obscenity laws, a careful reading of the 1923 court transcripts (housed in the Beinicke Library at Yale) finds that not only was there no discussion of “lesbians” in the court case, but that most of the same-sex references and actions that had been in the Provincetown Playhouse production had been excised for Broadway. More than that, not a single member of the press made mention of “lesbianism” when the case went to trial in 1923. As society at that time was grappling with new understandings and expressions of sexuality including homosexuality, God of Vengeance was important not because it was the first lesbian kiss on the Broadway stage, but because it forced audiences to question what they thought they knew about sexuality at all. In fact, it was precisely because of the lack of clarity about what we might call “lesbianism” today that the case against the play was eventually overturned in early 1925.

Paula Vogel is not the first individual to label the relationship in God of Vengeance “lesbian.” In We Can Always Call Them Bulgarians, one of the first books to offer a history of LGBTQ plays in America, Kaier Curtin devotes the entire first chapter to the play and anoints it as a work of lesbian drama. Years later, US queer Jewish performance artist Sara Felder would also recover the play as a work of lesbian art in her 1999 solo play Shtik! in which she reenacts the Manke and Rivkele scenes both in Yiddish and with the assistance of Barbie dolls.

There is no doubt that God of Vengeance offers audiences a unique window into same-sex female relationships for its time period, but to call the play’s central female relationship “lesbian” is ultimately an inaccurate reading of sexual history. In what might seem a counterintuitive argument, Asch’s work, precisely because it operates outside the contemporary framework of lesbian relationships, offers audiences a glimpse of a relationship that defies sexual categories and even language.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

This article was so deeply routed that it made me wanna but the play myself. You never truly know the impact of play when you just watch it. I wish I saw plays like this when I was in theater history.

Thank you so much for this excellent context and analysis. I remember Robert Beachy's argument in his book "Gay Berlin," which (and I apologize, it's been a few years) seemed to say that the modern birthplace of queerness as a social identity could be tracked to Berlin at about this time. He used the German term schwule (translated roughly as "gay"?) as an emerging signifier of identity used at the turn of the last century and into the Weimar era. Does this term appear at all--perhaps while it was being produced in Germany--in the discourse from the era about God of Vengeance?

For more detail on any of this, check out my book The Passing Game: Queering Jewish American Culture. https://www.amazon.com/Pass...