One thing you’re hitting on here is that it’s always about the perpetrator’s character development. But the person who this violence is enacted on, where is their agency? What about the impact on them? It’s never about them, it’s always about, “We’re doing it to show this stage in their trajectory.” But we need to be a bit more careful and ethical about that. It feels like it’s shock tactics. I see that a lot in television, like Game of Thrones, when Jaime rapes Cersei next to the dead body of their son. It doesn't feel like its been approached with care and responsibility. It just feels like it’s a horrific, traumatic thing; it’s simply assault on a screen.

Jess: And socially we’re in a place where we’re now talking about sex and sexual violence and gender and gendered violence, so it’s also a matter of pushing the envelope, like, what can we show? The audience wants to see something and then feel something in response. We’re in this weird place where words don’t have meaning anymore, they’re no longer thought of as actions. You can get away with saying whatever you want, maybe even doing whatever you want. Depending on where you are, who you are.

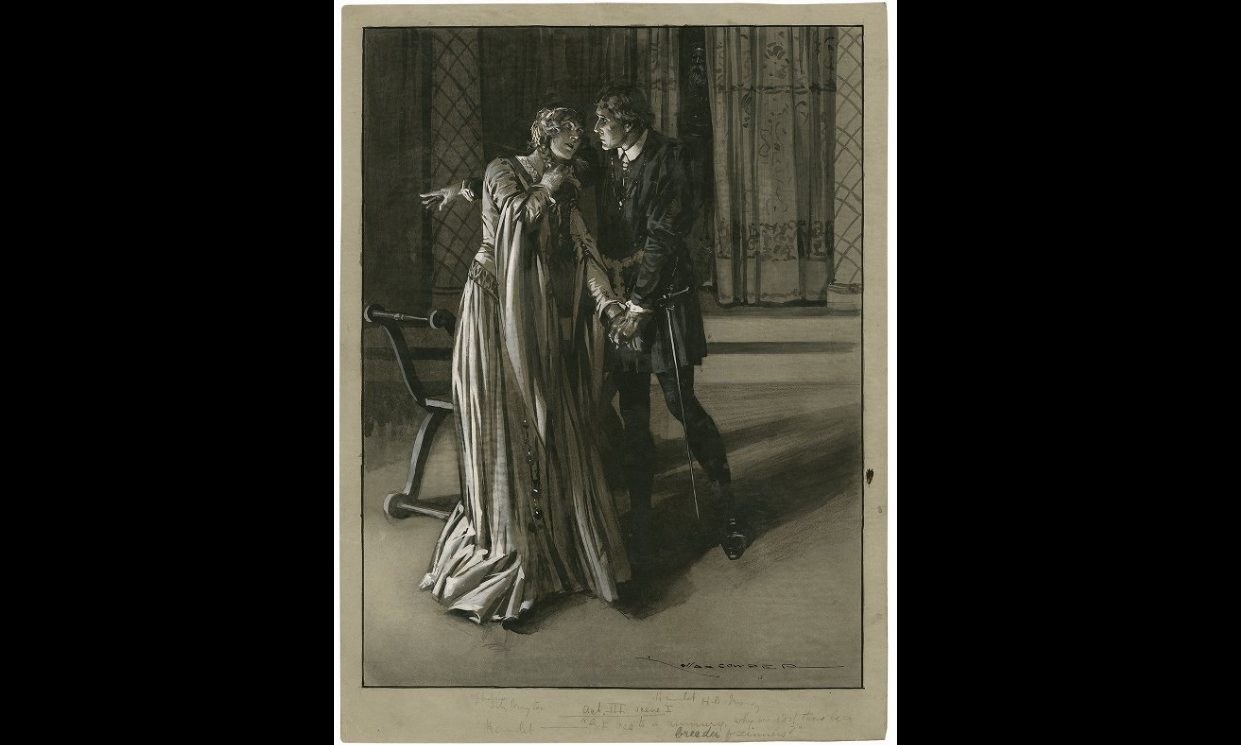

I wonder if there’s this larger thing happening, where we think words don’t impact people as much anymore, so we have to show moments of violence in order to demonstrate how grotesque or violent something is. The fact that it’s Hamlet violating Ophelia, it’s in his defense. We’re supposed to understand the inner turmoil he has because he’s perpetrating this violence, but also he has a lot of shit going on, right? Like, “Oh no, his father died and ahh maybe his uncle did…” It’s like another sign of his inner turmoil, and so it’s supposed to make us, in some weird way, feel empathy for his inner struggle. That’s part of the problem. These things are shown to make us feel empathy for the character, because they did this awful thing, but there’s other stuff happening so we should understand it.

What is the purpose of staging and showing such explicit violence? Is this a shorthand for thinking about moral flaws? Is staging violence a way of saying the perpetrator of violence suffers from mental illness?

Emer: The other week I was watching Bodyguard on Netflix. Spoilers for those who are still watching it. Julia Montague, Britain’s home secretary, is having an affair with the titular bodyguard, David Budd, who’s also a traumatized war veteran. Julia goes to wake David up one morning, and her rousing him leads him to strangle her for a minute or two. It’s a really horrific scene. She’s terrified initially, but then she spends the next few minutes trying to comfort him. It’s all about him somehow. And yes I know that comes from his own trauma or whatever, but also it’s about his character development

For all of us theatre artists, when it comes to staging these things, we have to think if we are traumatizing people. And not just audience members who are survivors. What about actors and theatre practitioners who are survivors as well?

Jess: That makes me think of Nanette, the Hannah Gadsby special.

Emer: Yes!

Jess: Part of what she’s doing is unraveling the idea that you need to subject yourself to violence in order to ease tension. She offers a joke of being mistakenly identified as a man on the street, explaining that a jealous boyfriend thought she was a male flirting with his girlfriend and threatened violence towards her, only to realize she was a woman and therefore not as threatening. The audience laughs and Gadsby moves on. But, later in the special, Gadsby returns to the joke to explain that she had erased the moment of violence when she was telling the audience the story: in reality, the man had brutally beat her rather than use her gender as a way of giving her a pass.

It’s an interesting exercise in the way she flips it and says, “This is actually what happened, this man physically assaulted me. I was scared to go to the hospital, I didn’t want to. I felt shame.” She doesn’t make an excuse for telling the joke and then revealing the truth, she just leaves it for the audience to grapple with in a way that expresses she is no longer willing to suffer the trauma herself. Or to say it’s not her responsibility to smooth this out for everyone else’s comfort.

That’s part of what’s so brilliant about her piece—the consideration, when telling stories, of who violence is either withheld from or shown for. Is the question then, “Are we responsible for other people’s feelings?” She’s unwilling to keep it to herself and then makes the audience responsible for dealing with the aftermath of the violence. In a way, the examples you mentioned are almost done like torture porn. Like, We want to show it to you so it makes you uncomfortable, but it’s titillating in some way. But Gadsby’s unwilling to make it titillating, she’s focusing on her own traumatic response rather than the empathy for the perpetrator of the violence, which is a complete shift.

Emer: And it’s important to say that Gadsby, as a survivor, is in control of the narrative. Whereas in Bodyguard, Game of Thrones, and productions of Hamlet, they’re just these incidents, but they’re always focused on how the perpetrator feels without any consideration for how the survivor feels. Gadsby herself is like: “This is what happened to me, this is my story, I'm the one who’s telling this, and this is how I’m going to talk about my trauma.” I feel that this is part of a wider conversation about addressing these things and giving people opportunities to tell their own stories, whether it’s through theatre, or film, or writing. I think especially of Emilie Pine’s essay collection Notes to Self and how she talks about her experiences as a survivor. Being honest and being able to shape that narrative is so important to her.

For all of us theatre artists, when it comes to staging these things, we have to think if we are traumatizing people. And not just audience members who are survivors. What about actors and theatre practitioners who are survivors as well?

Jess: This gets back to the question of: “Do we need to see something in order for it to impact us or for it to matter?” I think there needs to be a re-emphasis on the inherent violence of language and how words are being used. Even in claiming a position.

I went to this panel on early modern trans studies, and one of the discussion questions was on pronoun usage and doing the exercise of claiming your pronouns or not claiming your pronouns. As an educator, one of the things I’ve thought a lot about is having pronouns be something we all do. For some people that’s very accepting but for some people that’s a form of violence around their gender—having to claim it, having to out yourself in a way that’s really uncomfortable, having to position yourself in a way that makes other people aware of how your gender works in relation to how you’re presenting. So on the one hand that can be very liberating, but on the other hand that can be another form of violence done to you that pigeonholes you in this place of “But you don’t look like a boy” or whatever.

This is also another way of thinking about violence in terms of gender and the gender binary, and how that forecloses the possibility of representing yourself. When even if you say, “My pronoun is they,” what does that mean for people who aren’t used to that question? That makes it so people are like, “How do I use that? What do I say? Do I use ‘they is’?” These sort of strange questions around gender and language that come up when we’re trying to be more inclusive can ultimately be more exclusive.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I’ve been in 3 productions of Hamlet myself at the professional AEA level. I’ve seen between 5 to 10 live productions of it at various levels from academia, to the experimental & international circuits, and the union pro level, and viewed more on video. I’ve seen deconstructed abstract productions, ones with history layered on them, site specific ones, etc. I’ve seen almost all of the major film productions of it from 1897 to the present. This includes English language and other language films. I’ve read and seen plays and devised pieces BASED on it that have included the nunnery scene. In NONE of these productions has anyone gone out of their way to stage that scene with overt sexual assault. Your article doesn’t seem to list any specific references to said productions. I don’t doubt that they exist, but to say it is a trend, or even somewhat common (especially when you don’t cite specific productions) is not good scholarship. I don’t doubt there are some productions out there that HAVE done this, but you need to list them specifically for a reader to have a reference point. I could take then take the article into consideration as a specific criticism of implementing violence into certain productions, but as it stands right now I can’t take this seriously because you state this as something of an undeniable trend. Please at least list the productions in question (who produced them, directed, when, where, etc). With respect this reads more like a false straw-man argument without that information.

Hi Mark,

Thanks for engaging with this piece. As Emer mentions at the start, she's been working on this topic for an academic conference paper, which goes into a lot more detail about specific productions and examples. I'm sure she'd be willing to share that with you if you ask. Emer's PhD is literally about this, and she's an excellent and well-respected scholar in the field, so I'm inclined to trust her expertise here.

The format of this contribution to the series was a conversation between Jess and Emer that went well beyond Hamlet, and includes many specific examples from other forms of media. As the series curator, I stand by their work 100%. Keep in mind that just because something doesn't match your anecdotal experience, doesn't mean it isn't true.

All best,

Nora

Hi Hope,

I would love for you to share our conversation with your audience; it is indeed an important one to start and continue revisiting as we think more and more about the various types of trauma and violence we experience and are subjected to.

And thank you so much for sharing your important work with us!

JRP

Thank you both for sharing this important conversation, and thank you HowlRound for the whole series! I'd love to share this article (and the series) on the Festival's social platforms. Also thought folks might be interested to hear a related story shared by performer and producing artist Yvette Heyliger, about an actor getting triggered and passing out on stage while recounting violence during a performance. It's in the #HealMeToo Podcast's Episode 4 & 5 series, which shares our recording of a #TheatreToo Panel Discussion at this spring's #HealMeToo Festival. The panel was convened and moderated by Rachel Dart and Stephanie Swirsky, cofounders of Let Us Work, and features Hope Chavez of ART/NY and Aimee Todoroff of League of Independent Theater. Folks are invited to listen at bit.ly/hm2pod (Apple Podcasts) or healmetoopodcast.com (links to all the other players). The #HealMeToo Podcast is about halfway thru season 1, and will be continuing to share Podcast Extras of performances recorded at the festival through the summer and into fall.

Thank you all again.

Hi Hope,

I would love for you to share our conversation with your audience; it is indeed an important one to start and continue revisiting as we think more and more about the various types of trauma and violence we experience and are subjected to.

And thank you so much for sharing your important work with us!

JRP

Hi Hope, thank you so much! I just want to chime in with what Jess said -- please do share the article with your audiences! Thank you for the important work that you're doing! E