In Boceta’s 2020 adaptation, he successfully puts into question the role of the classical actor by openly displaying the struggle some of them go through when facing a monolithic conceptualization of how love and gender are defined in the works of the period. Francisco Trujillo, one of the actors, describes the conventional ending of early modern plays—multiple weddings—as “economies of love,” alluding to the strict heteronormative dynamics that do not fully connect with modern relationships. It is precisely for this reason that the dramaturgy of En otro reino extraño juxtaposes traditional love scenes, such as the sequence from the balcony in de Vega’s Castelvines y Monteses (Capulets and Montagues, c. 1606–12), the Spanish version of Romeo and Juliet, with dialogues from other plays that explore feelings of “friendship” with deep homoerotic tonality.

The selected scenes from de Vega’s La boda entre dos maridos (The Marriage Between Two Husbands, 1601) and La prueba de los ingenios (The Test of Wits, c. 1612–13) inserted into En otro reino extraño expose homoerotic desire that become even more visible as they are spliced into the traditional plot with its conventional ending. Something similar happens with the monologue from de Vega’s La vengadora de mujeres (The Avenger of Women, c. 1615–20), performed by Irene Serrano. This excerpt explores a self-proclaimed avenger, Laura, who denounces the restrictive roles reserved for women in society due to patriarchal prejudices and a lack of education at the time. Throughout the piece, actors and the protagonists speak equally from positions of non-conformity. Confounding periods and agency, actors and their characters confront each other face to face and establish a powerful dialogue between the past and the present about social entrapment.

The actors’ homes serve as their Zoom backgrounds, both for their informal conversations as well as for the scenes they perform. While there is something intimate about these everyday interiors that bring audience members closer to the actors, deep down we realize the performers are actors trapped without a stage. They dance in their living rooms, play guitar on their sofas, recite sonnets to their dogs, use the bathroom mirror to connect with themselves and the bathtub as a symbol of oppression. It is not until the end of the piece that we see the actors leave their homes—but only to face a greater emptiness: a nocturnal and deserted Madrid. The cityscape takes center stage at this point in the piece; the empty streets are defaced by solitude, like a dystopian space as Alejandro Amenábar imagined it in his 1997 science fiction movie Abre los ojos (Open Your Eyes).

If this means we have had to rip apart classical texts to seek humanity and empathy in our desolation, then so be it, for how wondrous is the function of art when resuscitated to quell our modern nightmare.

Other Dramatic Realms

Thinking about the piece’s title, which in English is In Another Strange Land, we wonder: what is this “other” strange realm that unfolds within the piece? It might be the lifeless city or the carefully crafted homes each person has had to stage. But it could also be a new way to approach the classics. The artistic team of En otro reino extraño not only deconstructs and broadens the more traditional perception of classical theatre, but I would even say turns it into an entirely new aesthetic experience. The final product is consciously unfinished and reveals the feelings of the actors just as much as those of the protagonists, and, in so doing, creating a genuine dialogue between the two.

Although the art of an actor consists in telling a story in the most convincing way possible, this piece reminds us there is also an individual who feels and breathes behind the mask. Traditionally, we audiences do not go to the theatre to plumb the depths of an actor’s true identity, nor are we interested in their ideas or feelings during the performance, and even less in their relation to classical theatre. What interests us is listening to the speeches that have carved an honorific place in world literature. However, the isolation we have experienced globally over the last months has shown us that we need theatre—no matter how it’s delivered—more than ever. Theatre that is lively, that is vulnerable, that creates community by actively connecting the audience with the artists. If this means we have had to rip apart classical texts to seek humanity and empathy in our desolation, then so be it, for how wondrous is the function of art when resuscitated to quell our modern nightmare.

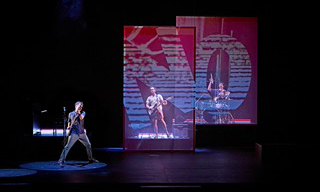

After the digital version of En otro reino extraño closed, Boceta had the opportunity to adapt it for the stage, which opened at the Festival de Teatro Clásico de Almagro (Almagro International Classical Theatre Festival) on 14 July 2020. The director decided not to further refine the piece when it went live and took the risk to faithfully reconstruct its “undone essence” to transmit to the audience the crucial importance of process, spontaneity, and sincerity in the original piece. The play follows the same fragmented structure as the digital montage and the actors engage directly with the public, sometimes remembering some of the conversations they had in Zoom and other times reaching out to the audience, taking the time to sit on stage and asking them how they are doing.

There are a great deal of modernized versions of Spanish classical theatre today, and diminishing the gap between the past and the present is something our contemporary directors must continue to explore in depth. En otro reino extraño does just this. Since the pandemic, the classics seem to have been retooled to inspire hope in the most genuine way, by my estimation at least. Without cumbersome backdrops, studied costumes, or complex scenographies, Boceta has created a way for us to cross a bridge to a “new strange land,” a revisited arcadia, where Spanish early modern theatre—and its main representative, de Vega—becomes perhaps more real, more human, and more combative than it has ever been.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you Barbara!

I only wish the piece would have subtitles to get to a wider audience. It is so difficult to explain how rich is it!

Thank you for this wonderful account, Esther. The piece is so moving, and I'm glad people can still watch it.

I am struck by how the classics can ground the feelings so many share during the pandemic. They take the work beyond the solipsistic exploration of lockdown to a deeper dive into what it means to be human, in this case by exploring what love means.