This past summer I attended a screening of the acclaimed documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution at a leading Off-Off-Broadway theatre. I had already seen the film (admittedly more than once) but was excited to watch it in a communal space where I hoped I could engage others in discussion about how to continue the work of the activists the film follows. As an introduction to the event, one of the organizers said she wanted to get to know who was in the audience. “Who here is the parent of someone with a disability?” Her question was met with applause and raised hands. “Who here works with people with disabilities?” She went on. “Who has a sibling with a disability? Who went to school with someone with a disability?” I waited through these increasingly distant associations to the world’s largest minority group, but she never asked the obvious question: who here has a disability?

As a disabled theatremaker with a personal stake in creating spaces that center disability, I can always tell, often almost immediately, whether an event is for disabled people or just about disabled people. I’m sure this organizer had good intentions, but I’m troubled by how often even those who say they want to engage with disability actually want to distance themselves from it. Often there’s a willingness to attend to some of the superficial elements of disability inclusion, but meaningful engagement stops there. Striving for an anti-ableist theatre community (and world!) certainly includes better physical accessibility and more frequent, accurate, and robust disability representation, but it also means undoing our internalized ableism and truly celebrating disability. We need to do more than include disability; we must allow it to shape our world.

Later in the summer I went to an event at Lincoln Center, In Conversation: Disability Artistry moderated by actor Gregg Mozgala. This evening showcased theatre by and discussion between playwright and dramaturg A.A. Brenner; actor and playwright Ryan Haddad; and Ben Raanan, artistic director of Phamaly Theatre Company, the country's longest-running theatre company that exclusively features actors with disabilities. In contrast to the conversations at the Crip Camp screening, which largely focused on disabled people as “inspirational” others, this discussion immediately felt rich. No one had to explain why disabled people are worthy of consideration in our own right outside of our potential utility to non-disabled people. Instead the talented artists onstage could spend their time on juicier questions like what does disability aesthetic mean to you, and how does it show up in your work? How do you navigate the intersections of your multiple identities? When do you choose to put yourself into your writing as a performer, and does that change your approach? One of the questions from the audience stood out to me: how do we move from disability visibility to disability artistry, and what comes after that?

Whereas disability visibility can be shallow or tokenizing, disability artistry says we are already here, we are already making exciting work, and the world of theatre will be made better by engaging deeply with that work.

I’ve always been skeptical of the notion of “artistry” or “excellence,” believing instead that everyone should have the space to express themselves creatively, regardless of skill. Nonetheless, I like this question because it invites disabled people to take ourselves seriously as artists. Whereas disability visibility can be shallow or tokenizing, disability artistry says we are already here, we are already making exciting work, and the world of theatre will be made better by engaging deeply with that work. I want to delve into both disability visibility and disability artistry, and I want to go further to dream about what disability makes possible on our stages and beyond.

Disability Visibility

Disability visibility is two-pronged. It requires both physical accessibility and representation of disabled people. Representation in theatre may be improving, but there’s a lot of work to do to build a catalog of disabled characters beyond what the theatrical canon (largely written by non-disabled people or those who don’t identify themselves with disability) has offered thus far. In “Naming the Trope,” Raanan helpfully outlines the stock characters disabled people are typically relegated to. These include the “Gentleman Freak,” “Magical Freak,” “Super-Crip,” “Misunderstood Weirdo,” “Rage-Filled Recluse,” and “Ambiguous Disability.” None of these tropes allow the disabled people who fill them to be complicated, fully formed human beings. Instead, these characters operate essentially as plot devices to teach lessons to their non-disabled counterparts. Given that these portrayals are often inaccurate at best and extremely harmful at worst, it’s up for debate as to whether or not this actually counts as disability visibility—especially because even these crumbs of representation are far too often given to non-disabled performers. Regardless it’s clear that to move from disability visibility to artistry we need complicated, diverse disabled characters and we need them written and played by disabled artists.

Another type of visibility through representation occurs when disabled actors play roles that were not originally conceived of as disabled, such as Ali Stroker’s Tony Award-winning performance of Ado Annie in Oklahoma! or the Deaf West production of Spring Awakening. This gives disabled performers much deserved opportunities to showcase their talents and often to add new layers to familiar stories. Of course, for disabled people to participate behind the scenes or onstage, they have to be able to get into the room. This is where physical accessibility comes in.

Physical accessibility includes ramps into buildings, suitable accessible bathrooms, and American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters, and it can also include things like having scent-free spaces or flexible rehearsal schedules. Unfortunately, it is rare for theatres to meet even the bare minimum for physical accessibility. This past summer, I worked on a project involving disabled characters that was accepted and then later rejected from a festival and multiple performance spaces due to the spaces’ inability to accommodate the performers I work with. (I myself have psychiatric and neurological disabilities as well as chronic illnesses, but I am physically non-disabled). And let’s not forget that Stroker had to wait in the wings before her historic Tony win and couldn’t later join the rest of her cast in celebrating their win for best musical revival due to the lack of ramp between the audience and the stage. Many performance venues need urgent renovation, but physical accessibility is only part of the picture.

I want stories that revel in disability, those that do not dilute themselves by trying to convince people that we’re all the same, but those that willfully delight in the beautiful divergences of our bodyminds.

Disability Artistry

This brings us to the second half of the question: disability artistry. Disability artistry likely means a lot of different things to different people. For me, it’s about work that is informed, from the beginning and down to its core, by some aspect of the disability experience. This doesn’t necessarily mean it needs to be “about” disability, but rather it can embrace a disability aesthetic or feature complicated characters whose lives include disability. That said, I am interested in theatre that centers disability as a driving force. I want stories that revel in disability, those that do not dilute themselves by trying to convince people that we’re all the same, but those that willfully delight in the beautiful divergences of our bodyminds.

For disability artistry, we need an active effort among audiences and artists to unpack their biases against disability and to instead embrace all that disability has to offer. As Jewish theologian Julia Watts Belser puts it “I fear that by conceptualizing disability primarily as an access problem to be solved, we fail to invite in the vibrant, transgressive potential of disability culture: of a ‘crip’ sensibility that celebrates disability as a way of life, a radically different way of moving through the world.”

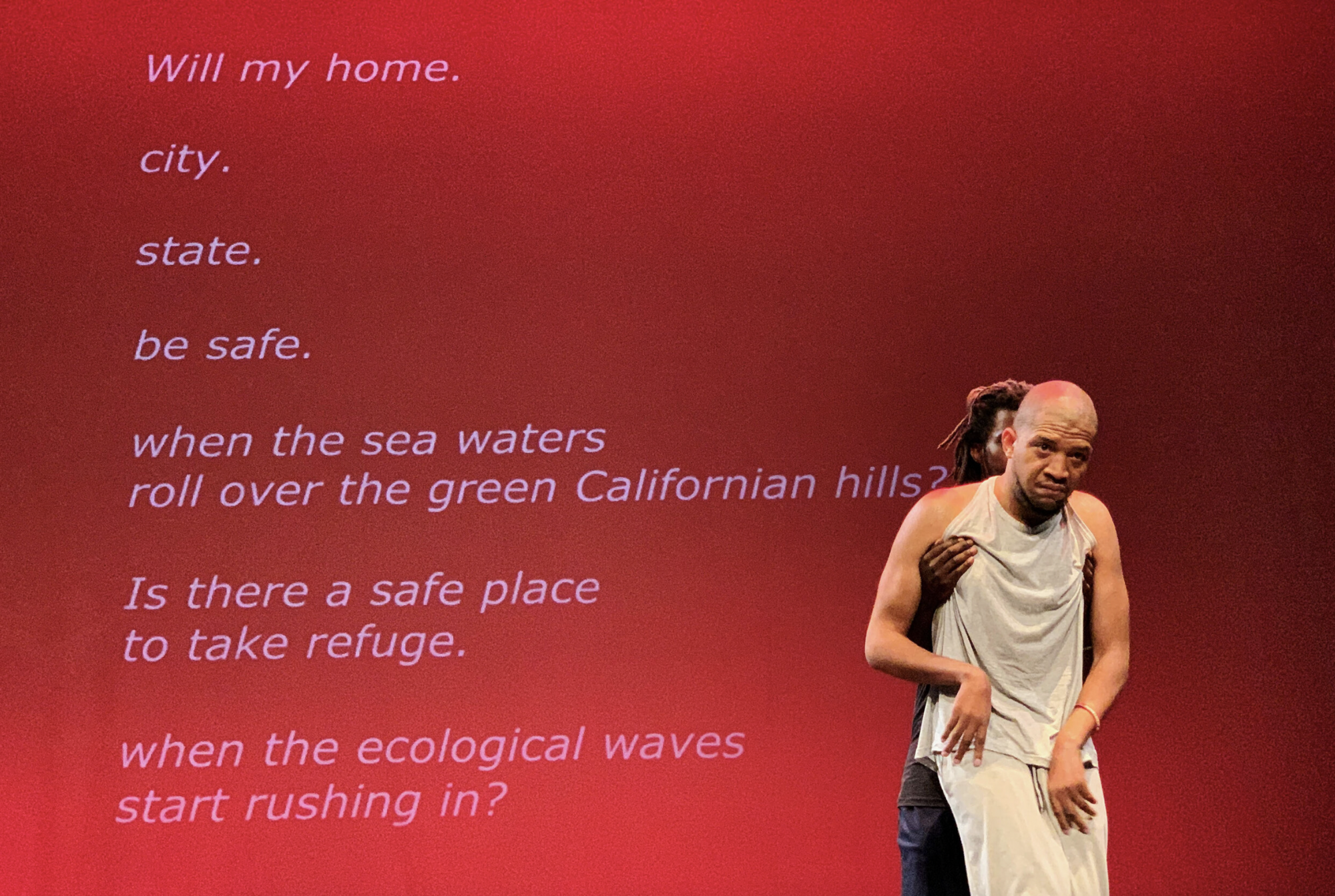

There are already many artists exploring the “vibrant, transgressive potential of disability culture” through theatre. As part of the Disability Artistry conversation at Lincoln Center, Ryan Haddad performed hilarious, overtly sexual personal stories and directly challenged any audience member whose instinct may have been to pity or infantilize him. Later that evening, A.A. Brenner gave new life to an old classic with a scene from Blanche and Stella, their queer, disabled reimagining of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. Moderator Gregg Mozgala did not perform but has spent his career delving into similarly rich disability-centered material including Teenage Dick, Mike Lew’s darkly comedic take on Shakespeare’s Richard III. Mozgala’s manipulative, power-hungry portrayal of perhaps the most famous disabled character in theatre history (who trades his reign over England for student presidency of his high school in Lew’s adaptation) is far from inspiration porn. The messy material questions how much our actions are due to our social situation versus our innate character and how much we must take accountability for them ourselves. This fall, Mozgala stars in Cost of Living at Manhattan Theatre Club, which explores the intimacy and vulnerability between disabled people and their care attendants.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for putting into words the thoughts that go through my brain every day as a multiply-disabled theatre maker. I am so excited to share this piece with my non-disabled friends and peers. You've captured the joy and pride I feel.

Thank you for bringing new words into our vocabulary - Access Intimacy and Disability Artistry.

You give context for those who are currently not living with a disability, so to begin considering new paths to our purpose in the performing arts. I am your partner in disrupting 'the show must go on' thinking, replacing it with community centered choices that may actually include the audience some day, inviting them into our process on stage! (ghasp) Now that could be an interesting play or opera!

Strength to you & thanks again.