Where the Wild Things Aren’t

Godzilla. Pyramid Head. Edward Cullen and Bella Swan. Almost everywhere you look, there’s a monster creating havoc on film, TV, video games, and in books of all kinds. Monsters show up everywhere because the idea is universal; its countless forms suggest the notion is encoded in our DNA. The combination of fear and imagination involved with monsters would seem well suited to exploration and exploitation in the theatre, but where oh where are the monsters on stage?

In an Age of Monsters

Monsters have hunted and haunted humans of all ages throughout time and across cultures because we’ve asked them to. We’ve invited them into our lives not only for thrills and chills but because they’re excellent educators. They teach us how to confront our fears by demonstrating that, for every monster that threatens to annihilate the civilized world, there’s a hero who rises to defeat it. And that’s reassuring. Though our terror may be aroused by a story, the psychological benefits are real.

Ours is an age of monsters—literal and metaphoric—and there’s nothing wrong with participating in the zeitgeist. Theatre has never been immune to cultural trends, nor should it be. One of the virtues of theatre, in fact, is that it appropriates political currents, new aesthetics and technological innovations in order to keep this ancient art form relevant and responsive to the passions of artists and audiences.

For those who would dismiss the metaphoric, political, and theatrical virtues of monsters in the theatre, I refer them to recent comments made by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, who received criticism for embedding fantastical elements in his latest novel, The Buried Giant:

There have been a number of reviews that have expressed almost like a horror that I, a writer like me, should be writing about dragons and pixies. And I feel that I have almost innocently stepped into some larger debate. The border between the popular and the literary has been becoming more and more porous. So I think the kind of tropes that you might say come from the world of fantasy, you know, monsters and the supernatural, some people are saying we have to be much more open to these things, we shouldn’t stigmatize or be snobbish about them because this will enable a literary tradition that is in danger of becoming stultified to reenergize itself. (BBC Radio Newshour, March 4, 2015)

In a good monster tale, we experience fear of the unknown, then fear of the known, and fear all the way to the finale when the monster‘s demise finally provides a welcome catharsis. Not exactly the kind of catharsis Aristotle was advocating—there’s too much spectacle involved for his taste—but still, that final release and relief experienced by the audience makes these stranger-than-life-and-death battles extremely satisfying.

Encounters with monsters are also complex. First, we look for likenesses to ourselves as a way of understanding or accessing the monster’s thoughts. As playwright Carter W. Lewis explains, “In most stories monsters are usually just bigger uglier slimier versions of us. We create them, so we provide them our virtues and flaws in some oddly distorted form.” Given shared attributes of humans and monsters, it seems our differences might be bridged—but they never are. Monsters are the ultimate ill-fated “other,” destined for exile or death…until next time.

While our similarities to monsters may unnerve us, it’s the shocking differences that grab our attention. Slime, scales, claws, and fur. Colors and shapes that are downright unnatural. Ossification, flames, missing body parts, or chimeras. Never lovely to look at but—horrific as they are—still, it’s impossible to look away…for long. We want to know what it is, what it’s made of, what it can do. Curiosity overcomes caution every time, and in horror stories at least, that’s bad news for the curious cat.

There’s a dearth of dramatic writing in this genre, as well, for mainstream theatres at least. Hopefully the publication Evil Genius: Monsters on Stage, an anthology of essays, monologues, and plays—along with the arrival of King Kong on Broadway—will turn the tide by offering new works that target fears of the twenty-first century. With horror, timing is everything, and as times change, so does authorial focus, because monsters are most effective when they tap into fears du jour, be it radiation (Godzilla), sexually transmitted disease (Dracula), or sharks (Jaws).

Belief in monsters requires faith in the unproven, it’s spiritual and mystical, and it’s what gets people truly involved.

The Monsters on Stage Project

As true believers in the theatrical and therapeutic values that monsters can bring to the stage, the theatre faculty at Transylvania University (the perfect institution for this project, right?) has dedicated this entire season to producing plays and teaching courses on this topic. The faculty—Sullivan Canaday White, Missy Johnston, Michael O. Sanders, and myself—wanted to share our fascination with students and playwrights as we explored the narrative, metaphorical, and theatrical dimensions of monsters conceived and written to be performed live…or at least undead.

Our first task was to define monsters in order to distinguish them from monstrous humans—lord knows, there are plenty of monstrous human characters in dramatic literature already. Here’s our definition:

An imaginary or mythical creature that is part or entirely nonhuman. It may take any form of plant, animal, object, machine, or alien being. It may mix human and non-human characteristics or combine animals into a chimera or hybrid. It may be large, ugly, and frightening, or it may be a little monster. To some degree, it should inspire fear, though it may be misunderstood.

The Monsters on Stage Project was launched in early 2015 and includes a call for plays; the forthcoming anthology; and a college theatre season. We solicited new plays internationally, and the response was overwhelming; clearly we’d tapped into a passion—or at least a curiosity—in the playwriting community. Within three months, we received more than 500 monologues and one-act plays from 400 playwrights across the United States as well as from dramatists in Canada and the United Kingdom. Scheduled for release by Smith and Kraus Publishers in 2016, Evil Genius contains 32 of the most vibrant and thought-provoking pieces we received, along with a history of monsters on stage written by Matt DiCintio.

Where Do Monsters Come From?

As we made decisions regarding selection, design, and production, we found ourselves immersed in subjects that are noteworthy because they generally don’t arise in conversations about dramaturgy and design. The first topic focused on the impressive cultural diversity of authorial inspiration. Several playwrights turned to international folklore: a Japanese demon named Kiyohime, who was spurned by a lover, turned into a serpent and sought her revenge; a Malaysian vampire, Penanggalan, that flies around as a severed head with entrail tentacles; and a Persian goblin-like creature that suffocates us while we sleep. Closer to home, there are characters inspired by an Appalachian favorite, Raw Head and Bloody Bones, and by an Internet-manufactured legend, Slenderman (his progeny in the anthology is Shadowman), that recently inspired a horrific real-life crime.

Environmental and scientific concerns embodied by monsters, such as the Deep Sea Viper Fish in Richard Dresser’s play The Melting, include climate change, pollution, bacterial infection, industrial accidents, artificial intelligence, and Internet trolls. Allegorical monstrosities appear as Self Doubt, Beauty, Jealousy, and Death (complete with black robe and sickle). There are creatures reimagined from popular culture—zombies, werewolves, and Jekyll and Hyde. Childhood fears inform frightful transformations and terrifying encounters. And there are mysterious incarnations of nightmares, the unnamed beasts that lurk about in our subconscious.

What Does a Monster Say?

Second, we identified a noteworthy distinction between monsters that don’t or can’t speak (they just are) versus monsters that do. Shakespeare gave Caliban something to say, but there have been few other monsters on stage that have spoken their minds. Sure, Dracula chats up a storm when he’s not a bat, but there’s something wrong with Frankenstein’s creature’s vocal cords, werewolves only howl and zombies don’t talk … fortunately. So what’s a playwright to write in terms of dialogue? It’s a challenge few writers have taken on, preferring to keep their “others” other by denying their monsters the powers of speech. But once playwrights choose a character, language is their next challenge.

Instead of rampaging through Manhattan, the monsters in Evil Genius use language as the method to express their madness. Their dialogue in these plays tends toward the poetic, the polemic, and a detailed narrative infused with suspense and shock value. That makes sense. Since monsters are larger than life, their modes of expression should be, as well. There’s also the sly approach that employs everyday language to seduce an audience into an everyday mindset until…the bite, the sting, the claw, the pain.

What Does a Monster Mean?

This led us to the third noteworthy topic: a monster’s means and meaning. There are narrative tropes in horror fiction and films: nature’s revenge, science run amok, and sexual predators, to name a few. But theatre, with its ability to present the abstract, anthropomorphize the monster, and visualize the metaphoric, offers ways to reinvent those tropes by prioritizing ideas above actions. Physical depictions and transformations may be less literal on stage than in film, but that can be turned to a playwright’s advantage. Fear is generated in the mind, and that’s always the theatre’s target: appeal directly to the imagination and deliver a startling vicarious experience.

Rather than characters in conflict with one another, monster monologues and plays present characters as conflict with the human condition.

How Does an Audience Respond?

This raises the topic of audience response. One of the take-aways from our fall production of Beware Wolf … And Other Nightmares (five world premieres of monster one-acts and monologues by Janet Allard, Mattie Bruton, Naomi Iizuka, Mark Stein and Jessica Wilson) was the important difference between “acceptance” and “belief” for audiences. Most of the time audiences are asked merely to accept the reality on stage, and that’s not difficult within the parameters of Realism because sets resemble actual places and characters speak and behave like recognizable people. But with monsters, audiences must use their imaginations if they’re going to invest in (i.e., believe) what’s happening on stage. It all boils down to the difference between “suspending one’s disbelief” and “choosing to believe.” The first thought is constructed as a negative, the absence of disbelief, a vacuum that leaves the question of belief unanswered. Commitment to believing is what really activates the audience’s imaginations. Belief in monsters requires faith in the unproven, it’s spiritual and mystical, and it’s what gets people truly involved.

To engage audiences at this deeper spiritual level, the playwrights represented in Evil Genius have been inventive in their dramaturgical strategies. Some portray the monster through a human point of view; others give you the monster directly. Some start with the monster, others withhold the creature until the final moment, and a few draw back the curtain slowly, offering terrifying glimpses of the unknowable and untamed. Whatever approaches the playwrights have taken, their monsters are extremely active. Most of them do the expected—deceive, intimidate, and destroy—but they also relate their irreal condition, and that’s very different than film. Since we’re not familiar with many of these creatures, their self-disclosure provides essential exposition. But more important, their explanations forward the dramatic action because the action itself is revelation built on fearful anticipation.

What Does a Monster Look Like?

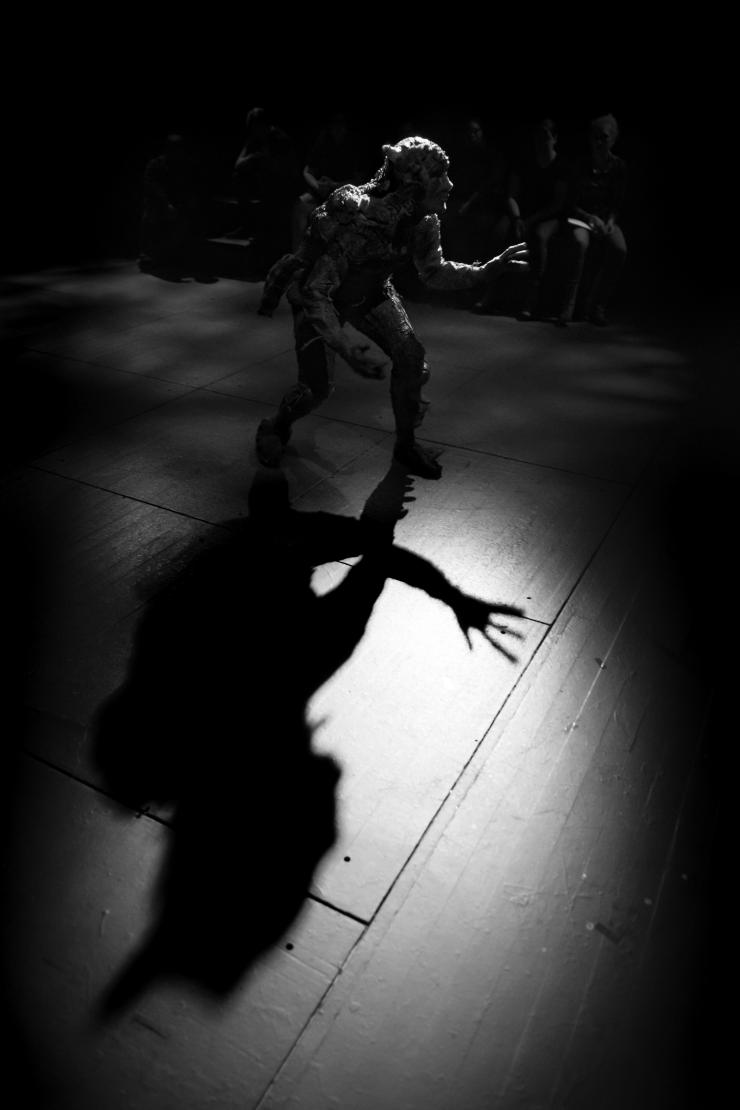

Finally, in terms of production, there’s the all-important consideration of figuring out what do these monsters look like? Details are everything, and the imagination reels at the possibilities: appendages, mutations, distortions, and more. Some monsters’ physical traits are implied by their names (Melto Man and Lady Mantis), while others are completely open to interpretation. The important thing is to understand the nature of the monster’s threat to our well-being; then find a visual representation that generates those fears.

Once upon a time the complexity and expense of makeup and prosthetics made it difficult to present monsters on stage throughout the run of a production. But in his article in the forthcoming Evil Genius, Michael O. Sanders—who created with his students all the creatures in Beware Wolf … And Other Monsters—describes new processes and materials that make the design and construction of fantastical physiques not only possible and affordable, but appealing.

Monster monologues and plays can be analyzed using conventional methods in terms of character development, conflict, and theme. But as you read along and envision the performance, you realize there’s something extra going on. Rather than characters in conflict with one another, these pieces present characters as conflict with the human condition. We know how to explore and question our own humanity, and we understand the uses of the scientific method in finding answers to questions in the natural world. But living with the unnatural and the unfathomable—especially when it endangers our safety—engages us in a different way. These are plays that can reach the most ancient mechanism of our reptile brain. Our response is visceral. It’s not just problem-solving; it’s fight or flight. It’s the moment we’re most alive.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I'm fascinated with monsters--the only type of horror I really want to watch and now, write. I can't wait to get a copy of Evil Genius. My haunted doll could use some company.