Confessions of a Creative Producer

Seven playwrights, five directors, and four producers walk into a room…

It’s not so much the set-up for a joke as it is the beginning of a fifteen-month collaboration that will ultimately manifest itself through an Off-Broadway production featuring the creative machinations of sixteen New York artists (including yours truly), otherwise known as the Women’s Project Lab—a two-year program serving playwrights, directors, and producers through a combination of artistic and professional development opportunities. When Producing Artistic Director Julie Crosby asked me to take the role as lead producer in the culminating show of the two-year Lab residency, I sat there with my mouth open for a moment, and then I said yes.

Allow me to rewind six months and provide a little more context:

Last year, Julie and her Associate Artistic Director Megan Carter sat down with the sixteen members of the WP Lab to discuss our second year culminating project, now titled We Play for the Gods. In the past, this project has often been site-specific, short pieces from playwright-director teams facilitated by creative producers performed in addition to WP’s main stage season. But this year is different. This year, Julie and Megan handed over one of their three season production slots to the Lab. And I really do mean handed over: they gave us a question to consider as a point of departure—and then let go of the reins. The product and process are ours to decide. Moreover, We Play for the Gods will not be the one-week-only production of past WP Lab projects, but rather a full-tilt Off-Broadway production at the historic Cherry Lane Theatre. Now, that’s what I call putting your money where your mission is.

Six months later, on the last day of our final retreat, and at the end of a summer of incredible collaboration with my fellow WP Lab members, I breathed a sigh of relief, downed a couple of margaritas (rocks/no salt), turned on the Indigo Girls (don’t judge), and confessed to myself that I had been unusually insecure for the majority of our time together. I’ve spent most of my theater career working in one of two models: the standard playwright-writes/director-directs/actor-acts model, and the check-your-title-at-the-door-because-everyone-is-everything-here model. But Women’s Project is asking for something different—for innovation, not just in content but in process.

Several months into the development of Gods, is it exciting? Absolutely. Is it fear inducing? Of course. Is it a professional challenge like no other that has led me to actively question the common assumptions of artistic collaboration in theater? Yup. That too. And therein lies the source of my summer-of-insecurity: a deep anxiety over collective assumptions about how a “collaborative” room is supposed to run, and the ways in which the WP Lab isn’t following the rules.

This article is the first of a series, which will capture the collaborative process between now and next June when we begin performances for We Play for the Gods, written, directed, and produced by the 2010-2012 Women’s Project Lab. So, in the spirit of confession—and collaboration—I thought I’d share a few of my takeaways.

Paradox is Bliss

Every collaboration needs leadership. There, I said it. Groups of individuals driving toward a common goal need a pilot, and an artistic process is no exception. And I confess that, at least in the case of We Play for the Gods, the process leader is not a playwright, or a director, nor an actor or a designer. It is a creative producer. And when we started this journey six months ago, I was uneasy in my role as a leader because a producer should never exert power over a creative process, right? That’s what I used to think too.

The thing is…leadership is not the same as power.

I quickly realized one of the most important contributions I can make to this project is to lead by constantly shifting the power dynamics and turning the assumed hierarchy on its ear. It’s a bit of a paradox—the idea that one must redistribute “power” in order to lead effectively—but (in my opinion), this is the role of the creative producer in our art form. Our entire job is to facilitate the creative process by assessing needs and aligning the human, logistical, and financial resources to match. The key word here is “facilitate.” The facilitative leader harnesses power and uses it to guide everyone in the room toward the best possible outcome.

Last May when we began our process for Gods, I stood at the front of the room and asked of my collaborators, “Where do you want to go?” and “What is most important to you?” Then, I proposed, “This is how we will get there.” But in order to do the getting, I needed to have—and ultimately give away—power. For the last six months, my fellow Lab producers and I have held in trust the collective vision of these artists, driving toward the best possible version of We Play for the Gods. Part of that trust means knowing when to let someone else drive, and when to take back the wheel.

Feedback is the Key

I will once again reveal my anxiety over introducing potentially foreign substances into the artistic process. Yes, creativity, resources, and room to fail are all excellent ingredients for a collaborative process, but I think well-facilitated feedback is chief among the list of needs not being met in the rehearsal room. I don’t mean feedback on the play, design, or the acting. I’m talking about feedback on the process itself.

During our weeklong retreat for We Play for the Gods, every session ended with a feedback session. I stood at the front of the room with colored markers in hand and listened first to what the artists felt worked about the day and about the process. Comments ranged from “I loved doing the composition work together. It helped build a common vocabulary,” to “Thank you for sending out the text in advance.” All the good stuff got written on one side of our poster paper for everyone to see. On the other side of the poster paper were—no, not complaints, but rather, “Proposals for Change.” Comments ranged from “I would like to have more time to revise the work,” to “It’s cold in here. Can we do something about the temperature?”

As a creative producer and facilitative leader, this feedback was critical to keeping the lines of communication open, building trust, and once again handing over the power to the people who should have it. It also provided a controlled, safe space for voicing concerns, which was invaluable to preserving productive energy. But part of building trust is being responsive to feedback, so each day came with a slightly tweaked agenda that addressed as many concerns as possible. And in the case of the temperature of the room, there was nothing to be done (finicky air conditioner), so the notes that night contained a warning for everyone to dress in layers.

I think well-facilitated feedback is chief among the list of needs not being met in the rehearsal room. I don’t mean feedback on the play, design, or the acting. I’m talking about feedback on the process itself.

It seems so little—dress in layers. But in the same way that the little annoyances can build up to a boiling point, so too can the little positive things build up to huge amounts of good will and trust. And throughout the week the feedback sessions became shorter and shorter. We were learning and adapting as a group. I have no doubt that those feedback sessions were the most effective way we built trust and unity in that rehearsal room.

A Producer’s Place is in the Room

Generally speaking, I’ve been taught to leave the art to the “artists.” And generally speaking, I’ve actively rejected the notions that a) a producer is not an artist; and b) should therefore stay out of the room and out of the way. But, for all my rejection of normative beliefs, there is still a part of me that proceeds with great caution when I walk into “the room,” or when it is time to make a decision that has artistic implications. That is as it should be. I should pause for a gut-check and consider the artistic consequences of my decisions, intended or unintended. But, I continue to learn that the more time I spend in the room, in conversation with my fellow artists, the better I am able to serve the project and the artists involved. This lesson has never been more salient than with We Play for the Gods.

One of the most immediate challenges of the piece was that my fifteen collaborators were saying loud and clear that chief among the priorities in this joint venture was that our group of individual voices come together as a cohesive whole. With a relatively short amount of time together over the summer, we four producers sat with Julie to strategize a structure that could house a polyphony of voices in service of a single story.

Walking in to our next full Lab meeting to tell a room full of playwrights and directors that four producers had just decided the structure of their next play was terrifying and uncomfortable. I thought we would be chastised for not being collaborative, for imposing a concrete decision on an artistic process without first getting on our feet and exploring (don’t worry, that part comes later). I felt guilty and insecure. That is, until the incredible playwrights and directors with whom I have the pleasure of collaborating said that they trusted us enough to go along for the ride.

Don’t get me wrong: they were not without their own questions and doubts. But each of these extraordinary women had enough faith in the process (and in their producers) to engage in a rigorous exploration of the structure we suggested, its opportunities, and its challenges. My experience continues to affirm that being physically present is critical to developing trust among any group of people. Thankfully, my fellow Lab members agree. They have never questioned the presence of the producers in the room. Not once.

I am not a Unicorn

It was not long ago that I felt completely alone in the world of American theater. I thought for sure I was the only one feeling caught between the “artistic side” and the “business side” of theater, and wanting desperately to use each to inform the other. Turns out, I’m not special at all. I’m becoming less unique every day. And I’ve never been more thankful to say that. This breed—the creative producer—is growing rapidly throughout the country and I confess I am thrilled by the trend. I continue to meet like-minded producers such as Julie Crosby, Megan Carter, and my Lab producer colleagues, Roberta Pereira, Manda Martin, and Liz English, and I learn more about our craft from each of them.

Julie has put us—creative producers—back in the room with playwrights and directors, where we belong, at the nucleus of the artistic process, and I believe our field will be healthier for it. I am only six months into what will be a fifteen-month process, and I have already grown immeasurably as a theater professional. Sitting inside this uniquely open collaborative process (which we are frankly making up as we go along), I know better how to facilitate and serve the creation of theater, though I am still nervous about what is to come. Will these facilitative tactics hold up through the entire process? Will the playwrights and directors continue to trust, and feel safe in our rehearsal room? Will the project succeed?

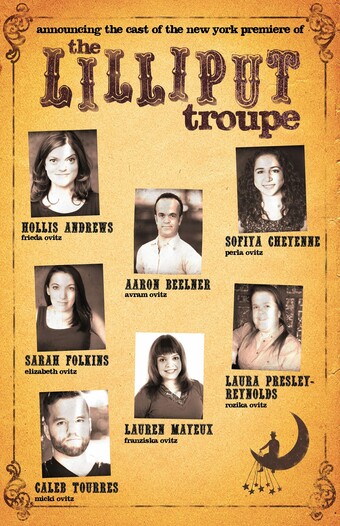

Photo by Chasi Annexy.

My last confession: a gut-check on all these questions tells me yes, yes, and yes. I truly believe Dominique Morisseau, Alexandra Collier, Andrea Kuchlewska, Kristen Palmer, Charity Henson-Ballard, Melisa Tien, Stefanie Zadravec, Nicole Watson, Mia Rovegno, Jessi Hill, Tea Alagic, Sarah Rasmussen, Liz English, Roberta Pereira, and Manda Martin, a.k.a. the seven playwrights, five directors, and four producers of the 2010-2012 Women’s Project Lab are on the best path possible. I also have no doubt that we will encounter artistic, emotional, and logistical challenges throughout the year. For me personally, I am looking forward to continuing to push on the assumptions of how we make art, and there isn’t a more perfect place in which to do that then this production process.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I welcome producers as equal creative partners as long as they welcome me with financial compensation equal to theirs.

Is that the case here?

I think that's a little apples and oranges, and I am not advocating equal creative partnership in every model.

But for the record, yes. In this process, all of the generative artists, including the creative producers are being compensated equally.

Wow. This truly sounds like an exciting process and I'm looking forward to seeing the result.

This is really insightful! Looking back, I realize some of my best experiences as a director have been in large part the result of a successful collaboration with a creatively engaged producer. A productive, ongoing conversation with a producer (or artistic director, depending on the project) can really provide a great compass for me.

Thanks for this thoughtful (and funny) column, Stephanie. You are not a unicorn and this will hopefully amass you many followers!

Thanks for this honest and insightful article Stephanie! I congratulate you for finding a way to be a creative stakeholder while still being a producer (ie, without trying to turn yourself into something else).

I responded especially to your distinction between leadership and power. Just because someone takes the first step doesn't make that person the supreme being. The best processes I've been in are those in which everyone has something at stake, everyone has their heart invested. In those rooms, I'm grateful to anyone who takes that first step, and honors our powerful collective investment. Can't wait to hear how this journey evolves!