Feast of Crispian

Shakespeare with Veterans

This day is called the feast of Crispian:

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when the day is named,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

— Henry V, William Shakespeare

Since 2013, the nonprofit Feast of Crispian of Milwaukee has helped military veterans cope with their personal trauma and “reconnect to others” and their “own sense of self” through the “words and stories of Shakespeare.” Over the past two years, I’ve been fortunate to help volunteer with Feast of Crispian and attend their two most recent productions: an original play And Safe Comes Home and an adaptation of Othello called Othello Deployed. After both productions, the veterans engaged in a talkback session with the audience, and expressed how important working with Feast of Crispian has been for them.

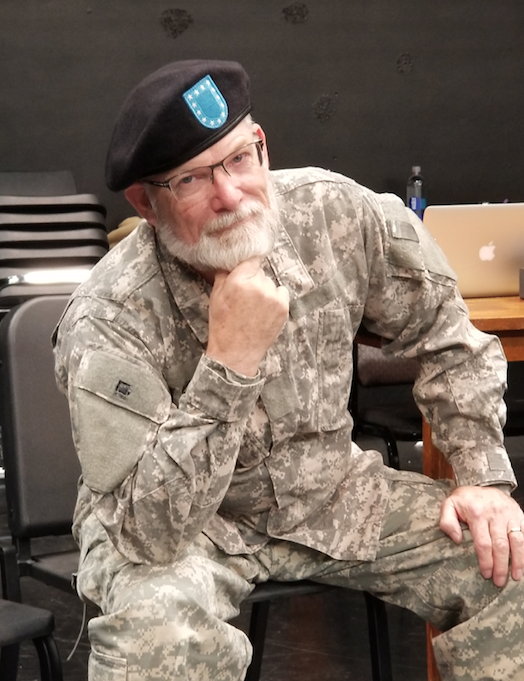

I interviewed Nancy Smith-Watson who, along with her husband Bill Watson and Jim Tasse, founded Feast of Crispian (FOC), and Tim Schleis, an army veteran and one of FOC’s actors.

Paul Gagliardi: Tim, tell us about your military background. Also, did you have any acting experience?

Tim Schleis: I served twenty-four years in the Army. My first three years was as a Combat Engineer (demolitions, mines, building roads and bridges), and the next eighteen years I spent on tanks. I was on everything from a Sheridan up to a M1A2. I served in Kuwait and Iraq and on US installations.

I had no real acting experience, not unless you count doing skits when I was stationed in Germany. We did skits as a form of entertainment for the locals and fellow soldiers. It was a great time.

Paul: What’s the background of FOC?

Nancy Smith-Watson: A piece of it is I’ve always been interested in social justice and activism. When we moved back here [Milwaukee] my husband Bill built the BFA program here at UW-Milwaukee, and he hired a lot of people to work with that program. One of the faculty he hired had worked with a Shakespeare & Company in Massachusetts, so we got to know what they were doing. One of their projects was called Shakespeare in the Courts, which is an alternative sentencing for juvenile offenders. We were really, really interested in that program, and they were really interested in exporting it.

However, it’s tough to get a program like Shakespeare in the Courts going in a place as big as Milwaukee, so we tried to explore similar programs. There was a lot of stuff in the media around that time about the real need for programs in the veteran’s community. For instance, there’s a real shortage of mental health workers for veterans, and a lack of veterans willing to talk to mental health professionals because they don’t feel it does them any good or they don’t want to step foot in the VA. One of the things being talked about was how effective arts programs were for people dealing with trauma. In 2013, the VA put out a report on how important it was to have arts programs for the recuperation of veterans. So it was a perfect storm. We wrote a strong curriculum, we were introduced to a series of supportive people that were in or connected to the veteran’s community who introduced us to the VA, they really liked the idea, and we got approval in two weeks!

Paul: Tim, tell us about your first sessions with FOC.

Tim: My wife and I had just separated for the third time; it was two weeks short of our twentieth anniversary. I had tried traditional counseling over the years. Before we separated, we saw a piece on a local TV station about FOC and my wife called for me. I went to my first meeting and I have been there since December of 2016. I didn’t know what to expect so I just went in and was nervous. I felt safe though after realizing that everyone else there had been through similar things as I had. I got more out of the first weekend than I had gotten out of any counseling sessions I had ever been to. Jim, Bill, and Nancy make it an easy-going and fun atmosphere. They don’t make you do or share anything that you don’t want to or aren’t ready to talk about.

Paul: Nancy, tell us about the first sessions when you worked with vets.

Nancy: Early in 2013 we did our first weekend intensive inside the VA with seven veterans. We were really shaking in our boots when we went in: Jim Tasse, who’s a veteran himself, was even wary about what we were going to be walking into. Among that group of veterans was a guy who was six foot three with tattoos on his neck, and we walked in and he’s sitting slumped in a chair with his hat pulled down over his eyes and we thought, “Oh my gosh, what is going to happen here?” And he turned out to be one of the most amazing guys: funny, intelligent, and a really lovely person—open to our mission. And that turned things over for us because you can never tell who someone is by just walking into a room and looking at them. And I have the same biases that I think a lot of the civilian population that doesn’t interact with the veterans has, which is that they are a certain type of person. And that has shown itself to be completely inaccurate. No doubt, the people that we work with, the clear majority, have challenges returning to civilian life after serving. But that is a tiny population of veterans. Veterans altogether are less than 1 percent of the population. And then those who have issues and access VA help is 1 percent of that. So it’s a tiny population that are really struggling.

And even those who have challenges, that’s why we use the word challenges. Those we work with who do struggle can’t stand the idea that they’re broken…it helps us to understand how Shakespeare is unique and has these powerful properties that are specific to the brain. It literally works the brain and helps to reconnect the brain because of the particulars of the language. But it also gives me—as a somatic bodyworker and an actor—this feeling about trauma that the veterans appreciate: that it is the natural way we as human beings deal with unspeakable events. When we speak about it, we call it PTS—we never call it PTSD. We tend to feel like it’s not a disorder, it’s the natural thing we do to stay alive and get through these terrible events. Most of us go through a traumatic event, whether it’s a fall, car accident, an assault; the difference between that and what the veterans go through is they go through multiple events, and that makes it harder. I think the veterans respond to what we do because we never come into this with the idea that they are broken. We say, “This was the way you needed to be in order to survive, but now it’s limiting your life, and let’s work on opening some doors to make life a little better.”

We always tell students and the veterans that there are no ‘bad-guys’ in theatre; there are just people who aren’t responding well to something that’s going on. You can’t play a bad-guy. It’s not as though the characters don’t do terrible things, but if you play a bad guy, it’s shallow.

Paul: Tim, what surprised you about acting with FOC?

Tim: If somebody would have told me that I would be acting in a play, much less a Shakespeare play ten, or five, or even two years ago, I would have said you’re crazy. I was worried about learning my lines; I wasn’t worried about anything else. What surprised me most was that once you learn your lines, how much fun you can have with the character. You get to be somebody else and use experiences in your life to evolve the character. We read Othello, then we were cast, then we got the script. We were giving direction on where the scene should go and look, but it was up to us how we got there.

Paul: Nancy, how did you prepare for working with veterans?

Nancy: The people at the VA asked us the same thing. And our response was that all of us have teaching experience: I worked with kids, Bill and Jim have taught for years. When you’re teaching acting to young people, one of the things you discover is a lot of people are coming out of trauma and go into the arts as a way of self-therapy. So we have a lot of experience dealing with people using art to find their way in the world, and to find an easier way. We were ready for people to have it touch their trauma. One of the reasons theatre works is the actors, and then in performance it’s the audience; having to get inside someone else and understand them creates empathy. By “getting-into” another person, you really have to think through why this character does the things they do. We always tell students and the veterans that there are no “bad-guys” in theatre; there just people who aren’t responding well to something that’s going on. You can’t play a bad-guy. It’s not as though the characters don’t do terrible things, but if you play a bad guy, it’s shallow.

We just did Othello, which was fascinating to do from a military perspective. We went into it with the focus of “here’s a black man in a white man’s world,” but as we listened to what our veterans were telling us about the play, it blew our minds. There is so much more to that play than the fact that Othello is black: the relationship between Othello and Iago is all about the battle-buddy relationship, and Othello instantly believes him because that level of trust is so high in the military. And that really opened-up our discussions of Iago when you look at it through the eye of “I’m losing my battle-buddy.”

In FOC when you share your story it no longer belongs to you, it belongs to the group, you do not have to carry it with you; the group carries it.

Paul: Tim, what challenges did Othello Deployed present to you as a veteran?

Tim: At first things were going well and my only frustration was waiting during rehearsal. Then Bill Watson added something to the death scene and I got real uneasy. I started having flashbacks of something that happened during Desert Storm. I didn’t say anything at first until during a rehearsal something happened. There was a scene with a knife fight between Cassio and Montano that I had to break up. I went a little overboard when I grabbed Cassio; Bill stopped us and asked what’s going on. So, I felt I had to tell my story to him. It was something I stuffed down inside of me over twenty-five years ago and had not talked about. I walked in on a fellow soldier raping a sixteen-year-old Kuwaiti girl and I stopped him. I had to use my bayonet to get the soldier off her. Once she was safe and out of there I put my bayonet away. I turned and was about to walk out. He jumped me from behind and a fight broke out. Two of my crewman came in and pulled me off him. In Kuwait if a girl is raped it is a death sentence for her if it is found out. I don’t know what happened to her.

During our talkbacks after our plays, I have shared this part of my story with the audience. In FOC when you share your story it no longer belongs to you, it belongs to the group, you do not have to carry it with you; the group carries it. If they use your story in a scene, you do not have to be the actor in the scene, someone else can tell the story.

Paul: Nancy, how did you approach working with veterans differently than with professional actors?

Nancy: The short answer is we don’t necessarily accept that we’re working with amateurs, so we’re doing it in a way that makes it a little more accessible to amateurs because we’re trying to make this schedule accessible to people who have jobs, and for some of them their levels of PTS and stress are high, so they can’t rehearse every night. But the rest of it, we are constantly shifting and adjusting to try and make it better for them and lead them to a better performance. We always say to them “this isn’t our major work: doing the performances is not our major work. Our major work is doing the work inside the VA, the intensives, and the classes that we do that allow veterans to explore emotions.” We don’t want to put them in front of an audience, we don’t call it performance, we don’t talk about acting values ever, we just play with the emotions and the language—that’s it.

Paul: What advice would you give actors and directors interested in doing similar work?

Nancy: I’d suggest taking a look at Stephan Wolfert’s series on Richard III. And while we do things a little differently than Stephan, no matter what you choose to do, you need to understand the power of what it is that you’re doing. We don’t think of ourselves as bringing anything to these people. We look at this in terms of not teaching something to the veterans, but to give them a space to explore things. We don’t have an agenda for how they should come out of this on the other side. We don’t even have the expectation that it’s going to do something better for the veteran. You can’t also be so cavalier about the stories you hear because there will be big stories you hear from the actors, and you have to be ready for those moments.

Paul: Tim, what have you discovered about yourself working with FOC?

Tim: In the military there is no place for emotions, they serve no purpose, so as a soldier you “pack them away in your duffle bag,” as I say. I packed my emotions away for over twenty-four years. In FOC I have found a safe place where other vets have gone through the same or similar situations that we can we relate to one another. So, I have found a place that I can unpack my duffle bag and play with my emotions and put them into a character or a scene and feel safe and won’t be judged for it. I found a place that I feel the level of camaraderie is similar to that of the camaraderie when I was in the military. I discovered that I do have something still inside me, and I discovered that I still have a lot of things not taken care of.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here