Hamilton

Five Ways Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hip-Hopped History Musical Breaks New Ground

At one point in Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical about “the ten-dollar Founding Father without a father,” the characters end a song standing on various boxes and benches—as if striking a pose on makeshift pedestals.

It’s a sly gesture, since the aim and effect of the musical is precisely the opposite—a point underscored at another moment in a self-deprecating complaint by George Washington, who calls himself

the model of a modern major general,

the venerated Virginian veteran, whose men are all

lining up to put me on a pedestal

—a line that in turn borrows from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance.

This glimpse into the show’s intricate layers of playfulness helps explain why Miranda and his musical are themselves being placed on something of a theatrical pedestal—embraced by musical majesties Stephen Sondheim and Andrew Lloyd Webber even before the show opened, attended by presidents, so hot at its Off-Broadway home at the Public Theater that it has extended its run three times yet is completely sold out. It recently announced it would transfer to Broadway this summer.

Critics generally have reacted ecstatically; my own review called Hamilton thrilling on at least three levels—as a series of exciting performances, as an entertaining and thought-provoking history lesson, and as the first-ever hip-hop opera.

If it’s not in my view a perfect musical (at least not yet; they have several months to work on it, which I hope includes some trimming)—and if there are no guarantees of commercial Broadway success—Hamilton seems groundbreaking in several ways, some of them surprising.

A Different Kind of History

Inspired by and adapted from the 700-page biography of Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow, Miranda’s musical uses a cast of two dozen (several playing multiple parts) to perform three dozen songs and raps over 160+ minutes in presenting the life of Alexander Hamilton—a life that is almost inseparable from the times in which he lived. As Chernow writes, Hamilton had a “unique flair for materializing at every major turning point in the early history of the republic”—from appearing as General Washington’s right hand man during the American Revolution to President Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton was a central figure in devising the structure of the government and the nature of the nation.

That Hamilton dramatizes American history and political figures is not what sets it apart. As I’ve written elsewhere, nearly every one of the forty-three U.S. presidents has been portrayed by name on Broadway or Off-Broadway over the past century. Hamilton’s sweeping scope certainly is not the norm, but also not unique. What most distinguishes the show from the usual historical fare on stage these days, though, is the tone. Along with All The Way, last year’s Broadway play about Lyndon Baines Johnson, Hamilton restores the kind of earnest, largely admiring portrait of political figures in American history that was far more common in the first half of the twentieth century.

More typical ever since the 1960s is the campy sensibility of someone like Alex Timbers, co-creator of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson and director of such recent history-tinted shows as Here Lies Love, a discoed history of Imelda Marcos, and Here’s Hoover, a Herbert Hoover-Elvis Presley mash-up. The closest Hamilton comes to campy is in its characterization of King George (portrayed effetely by Brian d’Arcy James when I saw the show, since replaced by Jonathan Groff). The king in full regalia sings in a Beatles-like pop melody as if to a jilting lover:

We have seen each other through it all

And when push comes to shove

I will send you a fully armed battalion

To remind you of my love

Mostly, though, Hamilton plays it straight, although its characterization of several specific historical figures could be considered revisionist. Much of this is a reflection of Chernow’s view. (“To this day,” the biographer writes of Hamilton, “he seems trapped in a crude historical cartoon that pits ‘Jeffersonian democracy’ against ‘Hamiltonian aristocracy.’” This is true even though “we are indisputably the heirs to Hamilton’s America, and to repudiate his legacy is, in many ways, to repudiate the modern world.”) Aaron Burr, Hamilton’s rival and ultimate killer, is pictured as an equal, not a villain, and indeed is most often the narrator of the tale. Thomas Jefferson is a dandy who moves like a slick Cab Calloway hipster. But the show clearly pays scrupulous attention to historical detail, and its assessments seem on the whole to attempt some balance. The show’s admiration for Hamilton is tempered with an acknowledgement that people are complicated, their lives messy. Hamilton, who seemed larger than life, had larger than life flaws and foibles; among them, he was at the center of what has been called the first political sex scandal in America.

This apparent commitment to historical accuracy is all the more impressive given what on paper might seem in-your-face anachronisms. While shows like Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson indulge in ringing telephones and twenty-first century slang to keep us safely and snarkily in the present, Hamilton uses similar techniques to make us feel transported to the past, as if we are observing history in the present tense.

A Different Kind of Rap

Holler If Ya Hear Me, a new musical using the music of the late rapper Tupac Shakur, opened on Broadway last June… and closed a month later, prompting some to ask (as playwright and hip-hop artist Idris Goodwin did on HowlRound): “Can hip-hop oriented drama be financially and critically successful on Broadway?”

What the questioning failed to take into account was that hip-hop has already been successful on Broadway. Depending on how you define the term, there have been hip-hop musicals on Broadway for two decades, starting with the Tony-winning 1996 showcase for Savion Glover, Bring In Da Noise, Bring In Da Funk—and very much including Miranda’s first and best-known musical In The Heights, which was nominated for fourteen Tonys (and won five of them, including “Best Musical”) and lasted three years on Broadway, until 2011. In The Heights was in many ways a traditional book musical, and it didn’t just employ rap music—just as Hamilton employs a range of musical styles, from R&B to jazz to pop to Broadway ballads.

What further distinguishes Hamilton is that it uses rap to tell a story that has no direct connection to any usual rap subjects or characters. This reaches its most remarkable expression when the show presents the debates Hamilton had with his ideological foes as rap battles presided over by George Washington as MC. Hamilton argues with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison over major issues facing the new republic. The debate over whether the federal government should assume the states’ debts and the need for a national bank includes Thomas Jefferson rapping:

When Britain taxed our tea we got frisky

Imagine what gon’ happen when you try and tax our whiskey…

Hamilton responds:

If we assume the debts, the union gets

A new line of credit—a financial diuretic

How do you not get it?

If we're aggressive and competitive

The union gets a boost. You'd rather give it a sedative?

Miranda manages to engage us in a debate over eighteenth century monetary policy. By some theatrical alchemy, the use of twenty-first century rhythm and idiom never feels startlingly out-of-place. Rather, the hip-hop approach feels like a modern translation, an effort to clarify rather than trivialize the historical moments.

What further distinguishes Hamilton is that it uses rap to tell a story that has no direct connection to any usual rap subjects or characters.

A Different Kind of Casting

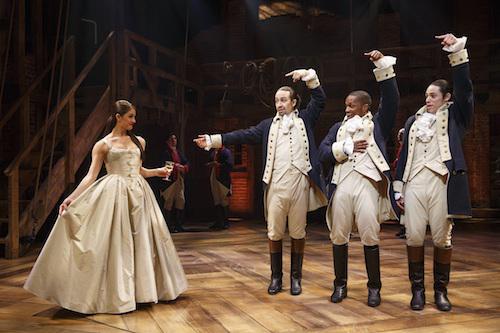

Nearly all of the characters in Hamilton—including Hamilton himself (portrayed by Miranda), Mrs. Hamilton (Phillipa Soo), Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom Jr.), and Presidents Washington, Jefferson, and Madison (Christopher Jackson, Daveed Diggs, and Okieriete Onaodowan)—are portrayed by performers of color. It is a casting that encourages us to look freshly at these characters.

When Leslie Odom Jr. saw a work-in-progress version of Hamilton, he himself was floored by the non-traditional casting for the Founding Fathers, such as Christopher Jackson, an African-American actor and composer who performed both in In The Heights and Holler If Ya Hear Me. “I watched him step forward and introduce himself as George Washington,” Odom told me, “and I never questioned it for a second. That’s a meta layer of this show.”

Indeed, Jackson in particular presents a historical figure who remains familiar to us in his characterization—George Washington as calmly authoritative. That he is also an African-American who raps and sings R&B counts as an irony, but not an undermining one.

Hamilton, an ambitious immigrant who had a miserable, impoverished childhood in the Caribbean, and became a successful, assimilated New Yorker, has a now-familiar archetypical American story, but one rarely associated with a founding father. Miranda, the New York City son of Caribbean-born (Puerto Rican) parents, whose birthday is five days (+225 years) after Hamilton’s, makes him an explicit stand-in for the nation as a whole:

Hey, yo, I’m just like my country

I’m young, scrappy and hungry

And I’m not throwing away my shot

With these performers, some descended from slaves, portraying the eighteenth century founders, many of whom were slave-owners, Hamilton, in effect, signals a new generation saying: We're America too.

A Different Kind of Connection With The Audience

The standard talk of a long-past Golden Age of American musical theatre includes the observation, as one scholar puts it, that “Broadway music and popular music were so intertwined as to be almost synonymous.” Hamilton’s score has the potential to restore a connection between theatre and popular culture, and the show as a whole promises to delight both high school history teachers and fans of The Notorious B.I.G., whose songs are sampled as readily as those by Gilbert and Sullivan.

A Different Kind of Traditional Musical

In “Sorry-Grateful,” a Sondheim song from his musical Company, one character sums up marriage:

Everything's different, nothing's changed.

Only maybe slightly rearranged.

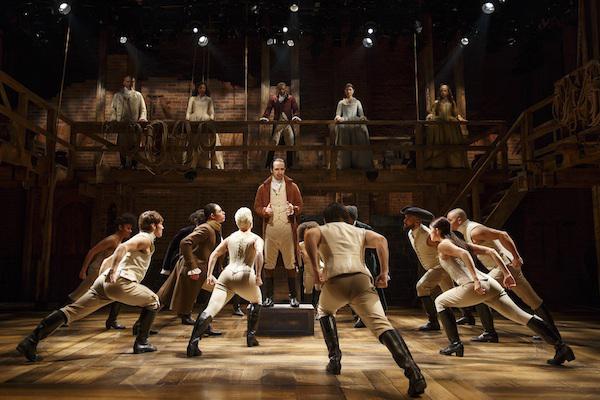

So much of what makes Hamilton groundbreaking is its return to familiar theatrical ground from the past, in a way that makes it feel freshly sown. There are not just allusions to musical greats like Rodgers and Hammerstein (à la The Book of Mormon, minus the snark), there is a hewing to theatrical convention, right down to the huge Les Miserables-style turntable center stage that helps keep the ensemble in what seems like constant motion—an illusion aided by Andy Blankenbuehler’s energetic choreography.

Hamilton can be viewed as an old-fashioned, sing-through musical, but it uses a relatively new musical form (rap) to cram in—artfully—as much exposition and historical fact as possible between the dramatic encounters. There is a love story in the show, though it is not always clear whether it’s with Hamilton’s wife Eliza or with his wife’s sister (Renée Elise Goldsberry). The emotions are big, filling the stage, but they are often ambivalent.

Hamilton’s score has the potential to restore a connection between theatre and popular culture, and the show as a whole promises to delight both high school history teachers and fans of The Notorious B.I.G., whose songs are sampled as readily as those by Gilbert and Sullivan.

Hamilton is full of love, wit, revolution, death, and regret, and women in silk gowns, men in breeches and brocaded coats with epaulettes, and some terrific lines, many of them given to Burr:

The art of the compromise:

Hold your nose and close your eyes.

There is a sense that this piece somehow transcends theatre even as it embodies it—or, as Hamilton puts it: “This is not a moment, it’s a movement.”

***

All photos by Joan Marcus.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Loved reading this so much! This show has been on my radar for some time. Now I just wish I could go see it!

Great article. It's so, so encouraging to see productions with as many layers to them that HAMILTON seems to have, and then to see it compared to the musicals you compare it to. It gives me hope that maybe we'll see more and more original pieces start to balance out the endless stream of movie/TV show adaptations and revivals.