PEN America, the Center for the Humanities at CUNY Graduate Center, and the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library presented Translating Plays and Playing With Translation livestreamed on the global, commons-based, peer-produced HowlRound TV network at howlround.tv on Tuesday 16 June 2020 at 10:30 a.m. PDT (San Francisco, UTC-7) / 12:30 p.m. CDT (Chicago, UTC-5) / 1:30 p.m. EDT (New York, UTC-4) / 18:30 BST (London, UTC+1) / 19:30 CEST (Berlin, UTC+2).

Livestreamed on this page on Tuesday 16 June 2020 at 10:30 a.m. PDT (San Francisco, UTC-7) / 12:30 p.m. CDT (Chicago, UTC-5) / 1:30 p.m. EDT (New York, UTC-4) / 18:30 BST (London, UTC+1) / 19:30 CEST (Berlin, UTC+2).

Translating Plays and Playing With Translation

Featuring Aya Ogawa and Jeremy Tiang

Tiang and Ogawa address translation as part of a playwriting practice, and discuss how they use language and translation in their own multilingual work, and how each aspect informs and affects the others in the writing, directing, and performance of their plays.

Aya Ogawa is a Tokyo-born, Brooklyn-based playwright, director, performer and translator whose work reflects an international viewpoint and utilizes the stage as a space for exploring cultural identity, displacement and other facets of the immigrant experience. Cumulatively, all aspects of her artistic practice synthesize her work as an artistic and cultural ambassador, building bridges across cultures to create meaningful exchange amongst artists, theaters and audiences both in the U.S. and in Asia.

She has written and directed many plays including A Girl of 16, oph3lia (HERE) and Ludic Proxy (The Play Company). Most recently she wrote, directed and performed in The Nosebleed at the Incoming! Series at the Public Theater’s Under the Radar Festival. As a director she most recently directed Haruna Lee’s Suicide Forest for The Bushwick Starr and Ma-Yi Theater Company. She has translated numerous Japanese plays into English including work by Satoko Ichihara, Yudai Kamisato and over a dozen plays by Toshiki Okada; many of these translations have been published and produced in the U.S. and U.K. She is currently a resident playwright at New Dramatists and a Usual Suspect at NYTW, and recent member of the Devised Theater Working Group at the Public Theater and Artist-in-Residence at BAX. ayaogawa.com

Jeremy Tiang is a translator, playwright and novelist, originally from Singapore and now based in Queens. His bilingual play Salesman之死 would have been performed at Target Margin this April, but has been postponed due to the pandemic. Past plays include A Dream of Red Pavilions (adapted from the novel by Cao Xueqin; Pan Asian Rep) and The Last Days of Limehouse (Yellow Earth, London). Last November, his translations of new plays by Chao Chi-Yun, Lin Meng-Huan, and Liu Chien-Kuo to mark the legalizing of marriage equality in Taiwan were presented at the Segal Center. Other translations include plays by Chen Si'an, Wei Yu-Chia, Zhan Jie and Quah Sy Ren. He has also translated books by Chan Ho-Kei, Yeng Pway Ngon, Zhang Yueran, Li Er, Yan Ge and Jackie Chan, among others. His novel State of Emergency won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2018. www.JeremyTiang.com

***

Esther Allen: Hello and welcome. I'm Esther Allen, a professor at City University of New York. And I'm here with Allison Markin Powell, who translates Japanese literature, works with the PEN Translation Committee, and has been a driving force co-organizing, Translating the Future, which is the conference that you're now attending. In the past weeks, we've seen in horror how massive global protests against atrocities perpetrated upon the Black community in the United States by the police seem only to have exacerbated that brutality. This has been a moment of awakening and a time for education. One valuable resource is the Black liberation reading list, published by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black culture at the New York Public Library. On that list, is "Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments," intimate histories of the social upheaval. An extraordinary book by Saidiya Hartman, who, among other things, is a former fellow at the New York Public Library, Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers. Hartman has just had a piece in BOMB Magazine titled, The End of White Supremacy, An American Romance, and I strongly recommend that you read her book and her latest article in their entirety. I'll quote one passage from the article. When the pandemic overtakes the city, they will die in greater numbers, they will suffer more. When the mob arrives, they will be as courageous as Mary Turner and call out the names of their killers. They will not yield, they will not be moved. In this other variant, the question is no less pressing. How is love possible for those dispossessed of the future and living under the threat of death? Is love a synonym for abolition?

Allison Markin Powell: Thank you, Esther. And thank you all for joining us for the sixth installment of our weekly series, translating plays and playing with translation, featuring two enormously talented people, Aya Ogawa and Jeremy Tiang. Aya is a Tokyo-born Brooklyn-based playwright, director, performer and translator, whose work reflects an international viewpoint and utilizes the stage as a space for exploring cultural identity, displacement, and other facets of the immigrant experience. Jeremy is a translator, playwright, and novelist, originally from Singapore and now based in Queens. You can read their full bios on the Center for the Humanities website.

Esther: This series of weekly one-hour conversations is the form that Translating the Future will continue to take throughout the summer and into the fall. During the conferences originally planned dates in late September, several larger scale events will happen. We'll be here every Tuesday until then, with conversations about the past, present and future of literary translation and its place in the world we find ourselves. Please join us next Tuesday at 1:30 for the first of a mini series within our program titled, Motherless Tongues, Multiple Belongings. The first of these conversations will be between Jeffrey Angles and Mónica de la Torre, inspired and moderated by Bruna Dantas Lobato, which will explore linguistic multiplicities in their writing and in their translation. Please check the Center for the Humanities site for future events.

Allison: Translating the Future is convened by PEN America's Translation Committee, which advocates on behalf of literary translators working to foster a wider understanding of their art and offering professional resources for translators, publishers, critics, bloggers, and others with an interest in international literature. The committee is currently co-chaired by Lyn Miller-Lachmann and Larissa Kyzer. For more information, look for [email protected].

Esther: Today’s conversation will be followed by a Q&A. Please email your questions for Aya Ogawa and Jeremy Tiang to [email protected]. We'll keep questions anonymous unless you note in your email that you would like us to read your name. And if anyone who was unable to join us for the live stream, a recording will be available afterward on the how around and Center for the Humanities sites. Before we turn things over to Aya and Jeremy, we'd like once again to offer our sincere gratitude to our partners at the Center for the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center, the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center, the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, and PEN America. And now over to you, Jeremy and Aya.

Aya Ogawa: Hi.

Jeremy Tiang: Hey.

Aya: How are you, Jeremy?

Jeremy: Surviving the present moments like us all. How are you doing?

Aya: Same, same, surviving, keeping people alive in the house. But it's lovely to connect with you like this, even though we're not in the same room.

Jeremy: Yes, likewise.

Aya: So, I just want to kick things off, Jeremy. I mean, I've known you for years really. We haven't been super close until now, I would say. But I've known you to be both a playwright and a translator, and many other things. And I'm just curious how you arrived at where you are in your career as a translator and a playwright.

Jeremy: I guess like, all the best things I sort of stumbled into it. I grew up in Singapore, which as you probably know, is a very multilingual place. So I grew up bilingual, speaking English and Chinese and also being surrounded by other languages. Then I went to the UK to train as an actor and sort of fell from acting into playwriting. And at a certain point, realized that translation was a way to make sense of all the different languages, and cultures, and identities swirling around inside myself. So now I sort of balance my own writing with my translation work, and I see them as part of the same body of work as a kind of spectrum rather than two distinct things. And it's equally important to me.

Aya: And what was your first translating gig or like how did you start translating work?

Jeremy: Well, like many novice translators, I set my sights impossibly high. So the first thing I tried to translate was a play by Gao Xingjian. Because why not start with a Nobel winning playwright. So I found his email. I can't remember who gave it to me. But someone gave me his email. And I emailed him, saying, "Gao Xingjian, may I translate your play?" And I stand by this actually, I wanted to translate it for performance because the existing translations of his work were done in a more academic way that I don't think would work as well on stage. And in fact, Gao Xingjian has very little performed in the English speaking world. And he phoned me, like I do not know why I included my phone number and the email, never do that. But Nobel Award winner Gao Xingjian phoned me and said, there's already a translation of my work. And it was this very polite Chinese thing. And he's like, so it's not very nice for there to be another translation. And I didn't really have the vocabulary at the time, talk about different interpretations. And also, like, I had no actual body of work to back me up. So it's like, thank you, Gao Xingjian. And I like to think that was an auspicious start to the whole thing 'cause starting my career from a point of humility has, I think, kept me aware of the need to, I guess, bring others into the conversation and sort of think more holistically about what I'm doing with this whole ecosystem, which at that point was not translate the work of a Nobel Prize winner. And then a little after that, I approached a Singaporean playwright who had actually been my teacher in high school and said, "May I translate your plays?" And he said, "Yes." And my translation was performed in Singapore. And I was like, "Oh, this worked. "I'll do more of it." And so yeah, kind of a convoluted way in but we find our own way to where we need to be. How about you, Aya, what was your path into writing and translation?

Aya: That’s so funny. I'm finding a lot of resonance with your story. I was born in Japan, and we moved back and forth quite a bit between Japan and the U.S. And that kind of gave me a pretty like disjointed childhood. It wasn't an unhappy one. But when I did land in California for middle school and high school, I really felt like I didn't know really where I was. And I also didn't know who I was. And so I started acting in the high school drama program. And that was actually a place where I finally felt like, oh, I could be here, I can live here, I can be myself here. And so my entry into the theatre world was through acting, and I thought I wanted to be an actor. I came to New York, I went to Columbia, and I did study some playwriting there and directing but I really thought that, I was meant for the stage. But quickly also realized this was in the early mid 90s, mid to late 90s when I graduated. The field did not have a lot of work for me, for someone like me. And it was very humbling and extremely frustrating to be in this kind of powerless position of the professional acting life, having to be somebody else that I have no control over. So I started more and more focusing on writing, I was working with a company that was very collaborative, and we would kind of devise our own work. And from there after I left I really primarily focused on writing and also directing simply because I didn't think anybody else would be interested enough in my work to direct it. So I just started doing that. The translation bit, it's funny. I had a day job working at the Japan Society for a very long time. And they bring artists from Japan to perform in New York and all over the U.S. And oftentimes, these pieces, whether they were traditional note plays or contemporary theatre pieces, they would have no translation. And being the kind of bilingual person that I am in the department, I would often be tasked to translate or create subtitles for these shows. That's how I stumbled into it, it's because it was part of my day job and I kind of for a really long time didn't want my translator identity to be the thing that people knew me for because 10 years ago, I would say, there was really still a sense that the translator is invisible, should be invisible, is like a filter rather than an entity themselves. But now I've reached a point, I think, in both of my writing and my translating work that I feel comfortable and in fact, really embrace both aspects of my work and think that they really feed each other and nurture each other. Do you find it that way? I mean, how does your translation work and your playwriting work collide or coexist?

Jeremy: I think first and foremost by expanding my sensibility because translation pushes me into all kinds of areas that I might not enter into on my own. Just because you're engaging with someone who lives elsewhere and works within a different theatrical culture. And that pushes you to explore that and what they're doing. And I find it gives me a whole new vocabulary. Translating plays from Singapore, and Taiwan, and Hong Kong, and China has kind of shown me what's happening in these theatrical worlds, which are different also. And then I bring some of that into my own work. My own writing has become much more multilingual than it was. And I use language, I think in a way that is more fluid. I think there can be a tendency in the English speaking world to use non-English languages as a kind of seasoning, like, here are a few non-English words just to add up flavor. But actually, translation has brought me to a place where I'm more fluent of language, and so actually this person would totally say the speech in Chinese or whatever, and let's just do that. So a few have become more open, but I guess it's chicken and egg. It's my tendency to want to be more open that's brought me into translation and made me wants to work in this realm. I think this is something that I'll continue to explore. They'll continue to impinge on each other in different ways, but they definitely are part of my work that enrich each other and I wouldn't want to let either of them go. Did you find the same that your writing and translation feed each other?

Aya: Yes, yes, they definitely do. And the way, yeah, I never really reflected too deeply on my deliberateness in using multiple languages in my own plays. But I think for me, it really came from wanting to challenge the idea of a monolithic white English speaking America in the theatre, and saying, actually, there's a whole world out there that I can begin to kind of show aspects of by bringing in other languages. But I have also found that as you might know, I've translated a lot of Toshiki Okada's work. And I've not just dealt with his text, but have also translated, like interpreted for him when he's like doing a workshop or during a rehearsal process or something, anything like that. And I've found that certain exercises that he's done or certain ways he has structured ideas and those exercises have subconsciously and directly affected the content of my plays. And so, and it's often like, much later on that I realized that that's happened. I'm like, oh, no, but it's not as if I am, in any way, imitating him or his writing style, but I think because the process of translation is so intimate, I would say, you're really entering into someone else's mind and trying as best as you can to see through their eyes, that I can't help but have that kind of leave some residual shadow on my own creative impulses. Do you find that too, like more than just like a language, like incorporating other languages thing? Do you think that other playwrights ideas have influenced your work in that way?

Jeremy: Yeah, definitely. I think as you say, you can't spend that much time with someone and not have some trace with them remain on you. It's kind of imprinting. And I think that that can be really, because the relationship is so close, it can be really fruitful, that sort of mind meld. It's a bit like the Borg, isn't it? As a writer, everyone you've ever translated remains in you. And so by working with such a good because we both worked with quite a range of playwrights. I think the influences on us then become really rich and multiple. I'm intrigued about Okada's specifically 'cause he has such a distinctive style. And is there an example that comes to mind?

Aya: Yeah, I mean, and this may sound so superficial, but so he has this exercise he does with his actors, or I guess he has used it to audition actors, and he has used it in part of his rehearsal process. It's a very simple exercise when one person stands up and describes the house that they are living in or their childhood home. They basically, one person described a space. And then the next actor has to come and describe the same space, even though they've never had direct relationship to that space. And for him, this exercise is not about one actor mimicking the other. But he describes it as when we speak and move in the world in real life, extemporaneously, we have an image behind, we have an image of something and we are trying to communicate that image using text and movement. And so text and movement are at a sibling relationship to each other, not a hierarchical relationship to each other. But when we're acting on stage, actors have to memorize their lines and their movement. And the movement tends to become like a child relationship to the text. So the text overrides the movement. So in his work, he's trying to deconstruct that, that artifice of the theatre, but that's not what has influenced me. It's just this very simple exercise of describing a house. Because I saw that so many times, I probably have seen like 30 or 50 people do this exercise of describing their home and it just, for me, I was working on a play called Ludic Proxy, which you've seen, and it was about, the first act is about a woman who lived in Pripyat, which is a town that housed the workers of Chernobyl and had to evacuate after the nuclear disaster and was never able to come back. And in the play, she's trapped somewhat in this kind of feeling of nostalgia for her childhood home and she just endlessly in her mind revisits and revisits her home and describes it. So it's very much like a weird shape or structure to borrow. But it definitely came from him, I have to say.

As a writer, everyone you've ever translated remains in you.

Jeremy: Yeah, that play immediately sprang to mind when you were describing the place exercise, because that is so vivid, isn't it? That the whole idea of trying to recapture a place that you've lost and can no longer go back to and then rediscovering it, but it's not the same. Which is, as I say, this occurs to me, it's also a metaphor for translation. So it sounds like you've worked really closely with Okada. Are you generally very collaborative in your writing and translation?

Aya: Yeah, well, I guess, as I was describing my translation process, it's very intimate and it is very, I guess, isolated. I'm lucky if I have some editors or proofreaders to work with me. But usually, it's just really me dealing with the text and dealing with the playwright. But with my own writing, I find that I depend heavily on collaborators. My actors and also my designers, and those conversations really have, are just essential to me being able to create my work. I actually always feel a little bit shy when I say I'm a playwright because I feel like the playwright, as known to the world, is someone who like actually sits at a computer and writes a lot of texts and like shows up with a complete script. And I like to show up with nothing at all and kind of play in the room with people before I start writing. So yeah, that kind of collaboration has been essential for my own work. And I imagine what the process must be like for you. I mean, I read part of your salesman play, which is almost entirely in Chinese. And I know you're working with a director, who is not you, who's not Chinese, culturally, but who has spent a lot of time there. I mean, is there a lot of rewriting that happened in the development process of the play with the director or how did that text come about?

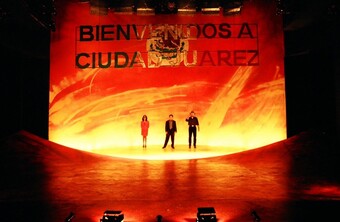

Jeremy: Oh, yeah, I mean, we've done quite a lot of workshopping. But also because this play takes, as its starting point, the production of "Death of a Salesman" in Beijing in 1982, which Arthur Miller himself directed, despite not speaking Chinese.

Aya: So this actually happened?

Jeremy: Yeah. In fact, you can watch the entire production on YouTube.

Aya: What!

Jeremy: Really good.

Aya: That’s crazy. That is amazing.

Jeremy: And also the translator of the text Ying Ruocheng played Willy Loman. So the director, Michael Leibenluft, came to me and said, "I've got an idea for a project, "we should take this production "that happened in Beijing in 1982 and do something with it." And we started in 2017. And initially, it was more of a recreation of the production and seeing what came out of that. And then we kind of realized that it was an opportunity to explore a lot of things that we'd both been interested because we both work bilingually and biculturally and also come from different directions because Michael's American, but went to Shanghai to study theatre, and study directing. And I grew up in Asia and then came to the UK and then to New York where I am now. So we kind of both have this experience of working in a different place and seeing how the stories we wanted to tell took a different shape when you transpose them. And as a translator, that's something that really resonated with me, this idea of, this play about the American Dream, what happens when you take it out of America and do it with actors who've never really had any contact because China in 1982, was just out of the Cultural Revolution, they'd had very little contact with the West. And a lot of the tropes of the play were unknown to them. And the play itself was not the monolithic work that it would be in New York, in the States, I should say. So all of that, I've actually forgotten where we started, but I'm just gonna keep going.

Aya: Yes, go.

Jeremy: This became a site on which we and the many actors we've worked with, and the larger creative team all brought our, I guess, cultural fluidity, because apart from the actor playing Arthur Miller, the entire cast was bilingual, and quite a lot of the creative team as well. So being in the workshops and then the rehearsal room was just this amazing experience of just moving between languages, translating for the people who didn't speak Chinese. But mostly we just went and it really took a life of its own. And I would emerge from each session with this wealth of material that I had to kind of bring into a shape and find a coherent form for. So we've been destabilizing the story in all kinds of ways. It's being performed by an all-female cast, just because I quite like the idea of a woman playing Arthur Miller. That has actually already discombobulated some people. Yeah, we had some strange emails.

Aya: Wait, so that process it sounds like it was really kind of a devising process.

Jeremy: It sort of was. I think it's not a true devising process in that I did start with a text. So rather than going in with a blank page, I kind of start with a text, bring it into the workshop. And in the course of the workshop completely rewrite the text. But not necessarily taking what the actors have said verbatim, but so going, oh, you did this, I'm going to take that there instead. I guess that is a form of devising. It's hard to pin down. For sure, I couldn't do it without the collaboration of the entire team.

Aya: And then the text that you brought into the room, was it actually in Chinese when you brought it into the room?

Jeremy: Yeah.

Aya: Aha, got it.

Jeremy: Yeah, no, I think that is a presumption that I write in English and self translate into Chinese. But actually, when I'm writing a Chinese, I become a different person than I am in English. And also, I think a lot of things just aren't possible. Like trying to imagine what these people in Beijing would be saying in English and then translating it wouldn't work for me, you kind of enter into their world's completely, and they're speaking Chinese. Just try to transcribe that.

Aya: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense to me.

Jeremy: Ludic Proxy also contained a lot of languages, which I was excited about. Because that was Japanese and Russian, if I remember right.

Aya: Yeah.

Jeremy: I was gonna say, do you speak Russian at all?

Aya: No, I don't speak Russian at all. And so I worked with a translator, Dramaturg, who helped me, and also in the development of that piece which spanned about five years. Because the play company, they were so generous and they commissioned me to create a play and they said, "You can make it about whatever you want." And I was like, "Great." And as soon as I started writing, or thinking about what to write some big life events happened, including the earthquake in Japan in 2011, and quickly followed by the death of my mother, then followed by the birth of my second son. So I kind of had to process all of this as I was creating this play and all these things, I'm sure you will recognize, have worked themselves into the play. The Russian section that I had a Ukrainian woman who was part of the workshop who was very generous and giving me a lot of feedback and I also worked with a translator who, at the end, kind of cleaned everything up and also came in as a speech coach. And the conceit being because the Russian section of this play is the memory of this woman. And she's casting the people in her American life into characters in her memory. It was okay for them not to be actually Russian or Ukrainian. Whereas in act two, which takes place in Japan after the earthquake, and it was about the present moment, and it was about the audience exercising their urgency and actually exerting their their ability to take action in the moment by choosing what one of the Japanese protagonist says and does, like a live video game through the course of the act. That was all conceived in Japanese and also developed with two Japanese actors who helped immeasurably in creating this like crazy, branching narrative. But it's funny while I was working on the Japanese, I was writing in Japanese, but I was also already thinking about the subtitles and being very conscious of what kinds of things were not translatable or deliberately omitted in the translation to keep the subtitles tight, and, yeah.

Jeremy: Even though you wrote that entire section in Japanese for the American audience, most of them would experience it through the subtitles.

Aya: Exactly.

Jeremy: Did you put in any bits that was just for Japanese speakers?

Aya: I can't remember if there was any kind of special treat like that.

Jeremy: But you think they would have had a different experience of that scene?

Aya: Absolutely.

Jeremy: Yeah.

Theatre culture is as interconnected anywhere as it is [in Taiwan]. So once you know a few playwrights, you kind of have access to them all.

Aya: Absolutely. And that was really a learning lesson for me too, because the reaction I got from Japanese audiences was just so different from non-Japanese audiences. And I mean, it's hard to kind of encapsulate right now. But my intention in wanting to place the audience in that spot of giving the audience the power to choose what that character does and says, I think that decision in terms of the theatre form, was received very differently from the Japanese audience and the non-Japanese audience. Because I think for Japanese people, those decisions were very real and high stakes, and it was a bit more of a reach, I think, for the non-Japanese audience. I mean, I think my plays are always kind of a litmus test in that way. It kind of leads bear like where the audience is at. I had another play that was about translation. And there was a scene with Spanish-speaking people and English-only speaking people, and it was really about how they were unable to communicate, but that immediately divided the audience right between the people who can understand Spanish and those who can't understand Spanish. And so there was a divide that occurred. That was fun, I think, it really like brought the audience alive and kind of aware of themselves and aware of like who else was sitting here in the theatre with me.

Jeremy: Yeah, I mean, I like what you said about a litmus test because quite often, I think with an audience, you tend to become part of this homogenous mass, kind of in communion with the play. And then when the play throws it back at you and goes, no, actually gonna split you up or gonna divide you up a bit. I think you start to think about your own relationships with people around you, and how a lot that is accomplished through language. A moment ago, you said something about the things that were untranslatable for the subtitles, which is always a fun concept, right? What is untranslatable, and in our own translation work, are there things that just don't make it across the divide.

Aya: Yeah. I mean, the stupid examples are just about the clumsiness of translation and grappling with, like, well, I can say this thing in three words in Japanese, but in English, it's gonna take up to 12 words. So I've got to do something about that. But I think that what I bring to the table as a translator, is my experience as a playwright and a theatremaker. So I'm not just kind of dealing with the text and the author's intentions, but I'm also really grappling with like cultural translation, cultural content, finding equivalent cultural markers in order to make that jump really quick into an American context.

Jeremy: Also, you're completely at home in both cultures, I'd imagine.

Aya: Well, it's complicated. I mean, I don't know how you, well, I imagine I've never been to Singapore, so I imagine that it's like everyone is kind of inhabiting multiple languages and ethnicities all the time anyway. But Japan is still such a homogenous place, and it's still very hierarchical and very kind of, like, if you're not Japanese, ethnically, or by blood, like you're not really Japanese, that kind of attitude. And so I find it really stifling, and so it's not that, I feel like linguistically speaking, yes, I would be fine. It's just my soul does not feel at home in Japan.

Jeremy: Yeah, I mean maybe I shouldn't upset at home but I guess having full access to perhaps, I don't know that that's interesting because someone who was born in Japan and is of Japanese heritage, where then do you position yourself as a translator?

Aya: Yeah. It takes some explaining. Actually, I'm just realizing that one of the first things that I say to Japanese people, especially Japanese playwrights, who are thinking of working with me is that I'm not Japanese. I might look Japanese, I might sound Japanese, I have a Japanese name, but that in my heart, I'm probably not as Japanese as I present, so that it's very important for me that they are aware of that gap. And for me I think that gap is what's exciting in a way that there's room there, which the room to make the translation possible. Where do you feel at home these days?

Jeremy: Well, cop out answer but I guess everywhere and nowhere. Like there's nowhere where I would say I feel completely at home. But at the same time, I guess I have gotten used enough to fluidity that I am able to make a home for myself wherever I am. It also helps, I guess, that Singapore is so multiple in so many ways. When I'm working with a playwright or a writer from China or Taiwan, it becomes really shorthand to go on from Singapore and be like, oh, okay, we get it.

Aya: Interesting. What is it that they get, do you think? Because it's not about the language, right?

Jeremy: It’s the idea that I will have grown up with familiarity with Chinese, although some expressions they find odd because the language has evolved, but also with English as a primary language. So it's that kind of in between this that I think a lot of people in former colonies feel where there are multiple layers of culture and you kind of have access to all of them, but also don't fully own any of them. And because Singapore kind of the Chinese were incomers to Singapore. After colonialism ended or rather I should say after it stopped being a colony, it was not a straightforward. I mean, it's never a straightforward process of going back to the previous culture, but because we were also geographically removed. And in my case, because I'm also mixed race, my dad was part Sri Lankan, and there was a lot of not really being able to go back to an existing culture and kind of existing in the state of limbo, where you have a bit of everything, but not all of anything. Which it turned out is a really good place to start translating from. So I think translation has become the only thing that really allows me to make use of all these parts of myself and all these places I've lived and all these influences on me and kind of synthesize them. So like, rather than the metaphor of translation as a bridge, I see it more as a crucible, like this thing that you bring all these things into it and come up with something else.

Aya: That's really beautiful.

Jeremy: Yeah, I'm really interested in people like us who are kind of multiple or hybrid who aren't entirely in one place, but kind of have offshoots. And the way translation is way of making sense of that. Yeah, going back to a point earlier about the presumed invisibility of the translator and the way translators have gained more prominence. It's been nagging at me that it's not actually every translator who is expected to be invisible. And I'm thinking back to even 10, 20 years ago with something like art, Yasmina Reza, Christopher Hampton was hyper prominent in the production of that. And there are certain translators who are given the status of artistic creator. Whereas for us it's been more of a struggle. So I'm interested in firstly, the power dynamics of that, but also whether our position as being in between, what that has done to where we stand vis-à-vis translation and writing.

Aya: Yeah, that's a really interesting point you bring up. And I don't know, I guess partially for me, because I seem to have fallen into every part of my practice, like backwards, like I didn't seek out translation as a path but I was kind of pushed on to it backwards and I was like, ah. So there was always a part of me that was not, I don't know, it didn't feel comfortable fully owning it and so that may have played a part in my feeling and kind of just like not whole in it. I don't know, maybe it's because I'm a woman. I don't know that. Maybe it's because I'm Asian. Yeah, I don't know. There's an endless kind of cycle of questions I can begin to unravel. But I do feel like actually now, finally, in the last few years, I've been feeling, I guess the reason I feel like I'm able to embrace my identity as a translate, as translating being part of my artistic identity is because that it actually requires a lot of responsibility and I am in a position of actually choosing who I work with, whose words do I translate, which playwrights do I want to introduce to an English-speaking audience? And that process has been really exciting to me.

Jeremy: Yeah, I mean, we're back to the theme of collaboration. And the way that it's really about forming a really close relationship with another writer and a text, and bringing your own artistic energy to it.

Aya: Right. How do you work with fans like with playwrights? Do you go and seek out writers to work with? Or how does it work for you?

Jeremy: At this point it's about 50/50. I'm both with my fiction and theatre translating work. Well, it's 50/50 fiction with play writing, I'm still seeking out more work and finding playwrights I want to collaborate with just because translation as you know isn't as prevalent in the theatrical world. But I've been quite lucky in that a lot of Taiwanese theatre particularly, the play scripts are just available online to download. And it's quite easy to get hold of them. So I've been able to read through a lot, and then reach out to the playwrights that I feel I want to have a collaboration with. And the other thing is that theatre culture is as interconnected anywhere as it is here. So once you know a few playwrights, you kind of have access to them all. And I found that when I find a playwright I want to work with, I often ask them, what are you interested in, who are you talking to, who's exciting you? And often those are the people that I also find exciting and interesting. And so I branch out that way. Yeah?

Aya: Yes, that's how it has worked for me, too. Toshiki Okada, he works with, I guess, are they a manager, managing company, or? Yeah, let's just say it's his manager. It kind of works differently there, but they handle several other playwrights and they have introduced me to a lot of other playwrights who are really working outside of like the traditional and conventional theatre landscape. I'm thinking of Yudai Kamisato, who he's Okinawan and but raised in Peru and so has this Japan, South America connection and a very international kind of point of view over history and colonization and Japan. And it's been really fun to delve into his work. And also Satoko Ichihara who is a Japanese, a female playwright whose work I find so transgressive and exciting and I just can't wait for somebody to produce her work here because I think that it would actually really resonate with an American audience.

Jeremy: Yeah, there's that. I think we're probably running out of time. Is it time for questions?

Allison: We have some questions. Your conversation has been flowing so organically, it was hard to find a spot to jump in, but we did. We do want to get to some of the questions from the audience and viewers. Thank you so much, it's been really, really fascinating to hear. I just like the way it's sort of like a therapy session where the juiciest questions come at the very end. All right, so we have a two-part question that came in. It would be great to hear Jeremy elaborate on how translating Arthur Miller, moving him across the language border into Chinese, also translated into his engendering as a woman. And the second part of that question is does the gendering have any parallel with the translation?

Jeremy: So I should make it clear that I have not translated Arthur Miller. Arthur Miller's lines in this play are all in English, and in a way that makes the presence of Arthur Miller stuck in that everyone around Arthur Miller is speaking in Chinese. But I've actually leaned a lot on Ying Ruocheng's existing translation of "Death of a Salesman," which was the one used in that production. And looking at the solutions he found to lack Arthur Miller's language, bring that in to the Beijing dialect of 1982 was a fascinating exercise in and of itself. I think indirectly though, the facts that the play transgresses linguistic borders made it easy to go and they will all be played by women. So yeah, I guess once you go off piste one way, it gives you license to it in many others.

Esther: We have another question. A more general one that I'm sure you both have a very vehement response to, from Jonathan Cohen. He wonders what percent of plays produced each year in the U.S. are translations. Do you have any idea?

Aya: I have no official statistics at hand, but I would say 0.3.

Jeremy: I would say one [crosstalk 52:35].

Esther: 0.03.

Jeremy: It's Siddhant Strindberg.

Aya: Oh, yeah.

Jeremy: Yeah. I mean, but that isn't it? Translations of living playwrights are yeah, probably 0.03. Yeah, I wish someone would do a count. But ultimately, that would be really depressing.

Aya: It also goes to show how at least in the theatre world right now, where really have been inward looking. And I hope that that can change. I mean, there are great theatre companies like the play company that are trying to change that.

Jeremy: Yeah. No, for sure. I guess I would like to see an expansion of what stories we see told on American stages. And I think that's a broadening of an existing conversation about diversity, because I think great strides have been made in terms of representation and diversity, but those often stop short at the borders of this country. And I just like to see that pushed further so that all American stories are told, but also stories from elsewhere can come in and be taught here through translation.

Allison: So there's a multi part question, questions for each of you and for both of you. For Jeremy, what do you see is the distinction between translation for performance and academic translation? Is it the inclusion of para textual material, or is it the style of the dialogue and Didascalia Excel? The second part of the question, is do you feel now that you have the vocabulary to explain to the first playwright you reached out to why to re-translation, that didn't take away from previous translations? What would you say to them now?

Jeremy: I'm completely outside the academic world. And I probably shouldn't have said academic. I would make a distinction in translation for publication, in which case the place to be read, and translation for performance, in which case you have to think about the other artistic collaborators and what a director, an actor would find most useful in the creation of their performance. I have no imminent plans to reach out to Nobel Prize winning playwright Gao Xingjian to relitigate our conversation from 15 years ago. But if I did, I would say I would point out to him that in the English speaking world, there are like a billion versions of "The Cherry Orchard," we seem to have a new one every three years. And why on earth shouldn't that be multiple versions of Gao Xingjian. Each new translation brings is an opportunity for different artists to bring their interpretation to the text, and to create something that is rich and vibrant and is one interpretation of hopefully many.

Aya: That reminds me of what we were talking about the other day, Jeremy, which is when I was asserting that there is no perfect translation or there's no complete translation, that that idea is false. In the same way as the idea that the translator should be invisible is, cannot be true. Because it is inevitably, as you say, an interpretation through one artist.

Esther: Here's another really interesting question that came in. Is the U.S. a good place to be a translator whose identity or home is part here, part there? Feel free to define good in any way you feel appropriate.

Aya: I think maybe good in the sense that because there is such a diverse population here, I'm trying to contextualize it as a translator. But I've definitely received a lot of work, translation work being here, I think more so than I would receive if I were living in Japan. And because it's so diverse and international here in New York, there are so many resources for people who are translating. And by that, I mean, in my case, like other Japanese people who I can bounce ideas off of, other cultural institutions and universities that have kind of the research material that I might need and things like that.

Jeremy: Yeah, I think in terms of infrastructure, living in New York, there are so many resources and also so many places to draw inspiration from, that it's good in that sense. But as we've talked about the monolithic nature of American theatre and how hard it can be to find a foothold in it, and to bring something different into it, that's more of a challenge.

Esther: Allison, you have another question?

Allison: Yeah. Well, it's another part of one of the earlier questions. This one was for you both. Do you feel when translating or writing a play that you are directing the show? Or do you feel that by interpreting a theatrical text, you are contributing something to the plays eventual he's on sound with the choices that you have made?

Aya: I don't feel that way. But I think it is a tricky question. I'm thinking particularly of my translations of Toshiki Okada's work. Toshiki is a playwright obviously, but he also directs his own work with his company in Japan. So in Japan, it's very hard to divorce his scripts from his direction. But he is very open in having his work translated into English. He has no kind of hang ups about how that text is eventually staged in America, He's actually, I think, excited by the idea of other people interpreting and directing his work in ways that he couldn't have imagined. So, I do always feel that in order to get inside the text, and inside his point of view, it's very helpful to understand how he directed it and how his audience received his work. It helps me create a context for the American audience to receive the translated work in a similar and perhaps, like parallel way, but I don't think that it really dictates anything about the staging or the direction itself.

Jeremy: Also, Aya, you are a director. So, I think, does that bring an awareness of what the direction of a piece would require in your work? Like, do you ever have the idea if I directed this, this is what I'd do.

Aya: It’s so funny. In terms of my translations, like I have no desire to direct them because I've already had such a personal relationship to them. I think it might be. That's where my breaking point is. In the same way, when I asked you if you would ever direct your own work, you were like, "No, I need my other people." Yeah, that's where I would draw the line.

Jeremy: Yeah, I realized at some point that I don't really use stage directions even in my own writing. It's like, you decide. I like the collaborative nature of it, of just being able to hand it on to someone else to have them do the interpreting.

Esther: So I think we've run out of time. What a wonderful conversation! I learned so much from both of you. It was such a pleasure to listen to you talk and I wish we could go on for another long while, but we're out of time.

Allison: Thank you both so much, Aya and Jeremy. And once again, we'd like to thank our partners, PEN America, The Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center, CUNY, The Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, and the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center. Thank you, everyone for being here and we hope to see you again next week.

Aya: Thank you.

Esther: Bye.

Allison: Bye.

About this Conference and Conversation Series

Translating the Future launched with weekly hour-long online conversations with renowned translators throughout the late spring and summer and will culminate in late September with several large-scale programs, including a symposium among Olga Tokarczuk's translators into languages including English, Japanese, Hindi, and more.

The conference, co-sponsored by PEN America, the Center for the Humanities at The Graduate Center CUNY, and the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, with additional support from the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center, commemorates and carries forward PEN's 1970 World of Translation conference, convened by Gregory Rabassa and Robert Payne, and featuring Muriel Rukeyser, Irving Howe, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and many others. It billed itself as "the first international literary translation conference in the United States" and had a major impact on US literary culture.

The conversations are hosted by Esther Allen & Allison Markin Powell.

About HowlRound TV

HowlRound TV is a global, commons-based peer produced, open access livestreaming and video archive project stewarded by the nonprofit HowlRound. HowlRound TV is a free and shared resource for live conversations and performances relevant to the world's performing arts and cultural fields. Its mission is to break geographic isolation, promote resource sharing, and to develop our knowledge commons collectively. Participate in a community of peer organizations revolutionizing the flow of information, knowledge, and access in our field by becoming a producer and co-producing with us. Learn more by going to our participate page. For any other queries, email [email protected], or call Vijay Mathew at +1 917.686.3185 Signal/WhatsApp. View the video archive of past events.

Find all of our upcoming events here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here