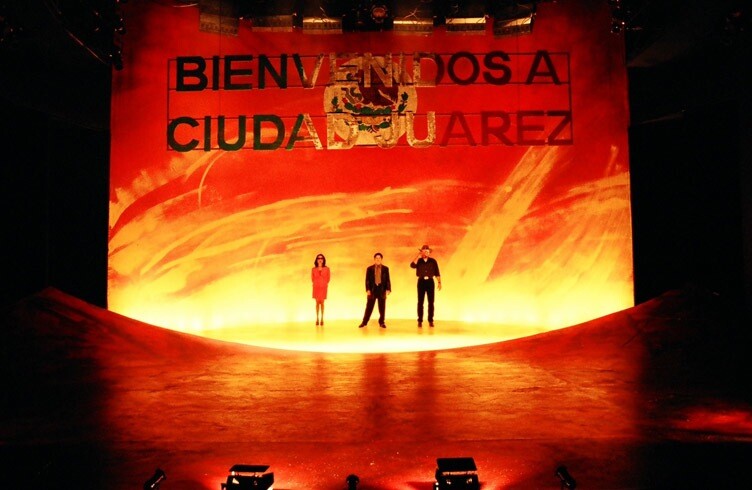

Octavio Solis is one of the most prominent Latinx playwrights of our time. He has written over twenty plays that have been performed at prestigious venues such as the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Denver Center for Performing Arts, the San Diego Repertory Theater, Dallas Theater Company, and many more. He has also taught creative writing at universities around the United States. His work incorporates the Mexican American experience of the border, bringing Chicano culture to the mainstage. This interview is part of Glenda Y. Nieto-Cuebas’ and Erin A. Cowling’s work on Siglo Latinx, a larger project that examines how Latinx artists are updating early modern Spanish theatre to reflect their experiences. Solis discusses how growing up in El Paso, Texas on the Mexico-United States border shaped his work, focusing on his adaptations of three pieces from the Baroque period: Man of the Flesh (from El Burlador de Sevilla), Dreamlandia (from La vida es sueño) and Quixote Nuevo (From Don Quijote de la Mancha).

Glenda Y. Nieto-Cuebas: How did your background and upbringing in El Paso influence your work?

Octavio Solis: I was born and raised in El Paso, Texas by immigrant parents. My father was undocumented in his first year; he was apprehended when I was a baby, and my mother pleaded with the officers not to take him because she had to go to work, and no one could care for the babies. They gave her a number for a judge who might offer a reprieve since they felt really bad for her. It was a different time, they weren't quite as severe as they are now, though that varies from person to person. My mother contacted this judge, who granted my father temporary residency while he arranged his papers before finally becoming a permanent resident. My parents are now full American citizens and have been since the early eighties, when President Reagan offered amnesty to all undocumented people. I grew up half a mile from the Rio Grande, so I saw the grim and sometimes macabre games of cat-and-mouse that the Border Patrol would play with the immigrants coming across to find solace and haven in this country. We were caught up in the middle of that.

I still could not get over this nagging feeling that I was a child of the border, and I was a little lost as an actor for a while.

The border made a deep impression on me, and so did El Paso. I didn't realize how much I was a child of the desert, even if I couldn’t wait to get out. I really wanted to study theatre. I did stage work early in high school and wanted to be a stage actor. I pursued that through four years of college in San Antonio, three years of grad school in Dallas, and one year in England. But I still could not get over this nagging feeling that I was a child of the border, and I was a little lost as an actor for a while; I couldn’t get work. I decided to become a writer to show off my acting, because I would cast myself in these plays. That didn’t work since audiences were more interested in the play than in my acting. That’s essentially how my career as a playwright started.

I still felt lost until I found a theatre company, Teatro Dallas, that asked “Why don't you write about your culture? Why don't you write us a play about who you are and see what you find there?” And I did. I have never looked back since. Although I had studied all these great playwrights—Harold Pinter, Henrik Ibsen, William Shakespeare, Bertolt Brecht—all these fine voices, I never thought I could be these guys. I would never be them. But no one could adopt my voice and bring in the border's dynamic, fluid presence, politics, and tensions like I could. So that’s when I realized that El Paso was the way to go.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

On behalf of Glenda, Octavio, and myself, we hope that you enjoy the article and check out part 2!

We would also like to acknowledge that funding for this project has been provided by Ohio Wesleyan’s Theory to Practice Grant and a Project Grant from the Office of Research Services, MacEwan University. This interview was transcribed by Amanda Fuenmayor, MacEwan University.

I loved the article! It's amazing! Waiting for part two :)

Thanks so much! Part two is now available here.