URGENCY: Slow Down

As the people with the stopwatches, stage managers keep an eye on schedules and breaks to ensure goals are met by the end of the day. With limited hours in the week, shrinking rehearsal periods, and the ever-looming deadline of opening night, it feels like compulsive urgency is, in fact, a necessity to create theatre. It’s unshakably rooted in our ethos—just typing out the words “slow down” feels blasphemous in a way.

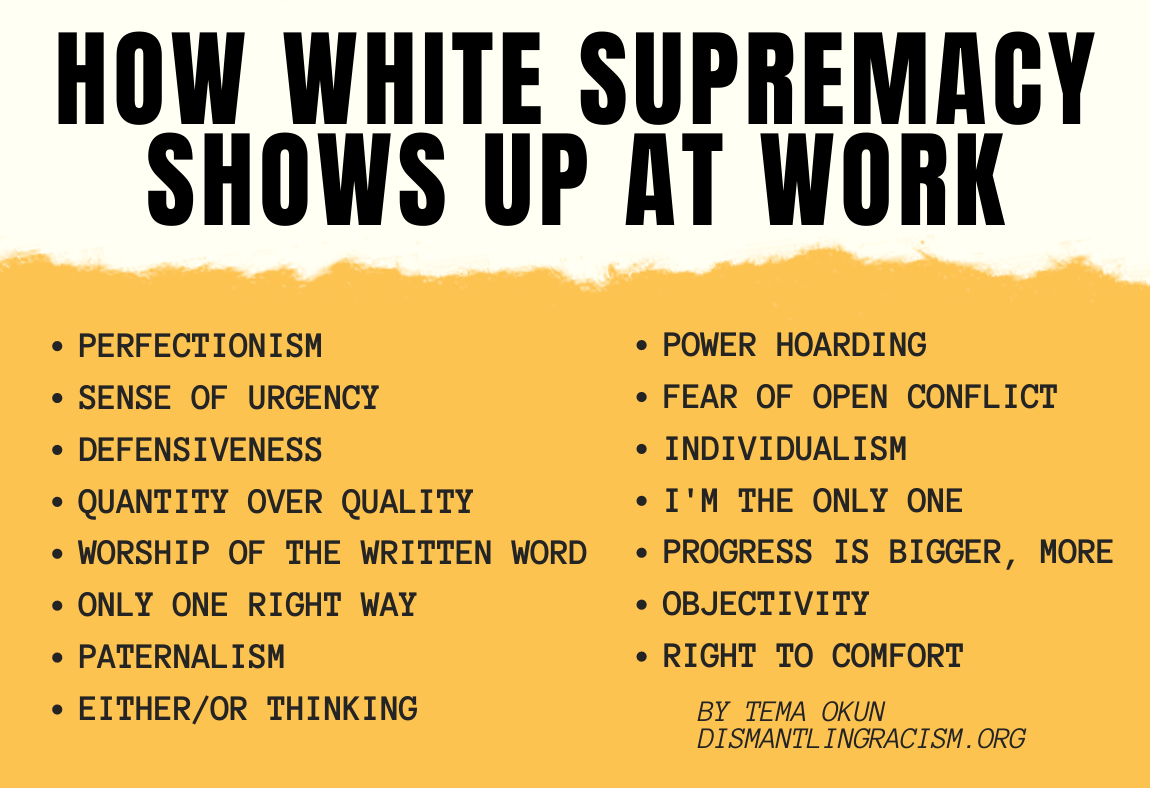

But when urgency is the driving force, it doesn’t actually make our work better, it only serves to squander thoughtful decision-making and cultivate environments where oppression and abuse thrive. For example, stage managers may use urgency as a justification for discrimination by saying there “just wasn’t time” to bring BIPOC people into the conversation. By choosing a quick solution over ensuring BIPOC people are part of the decisions that affect them, valuable insight is lost and solutions that favor white people and white-centric values are inevitably reached.

Many people are deterred from speaking out against microaggressions, harassment, and abuse during an individual project because it will be over soon and they don’t want to be the one responsible for disrupting the already crammed process. Or, if they do speak up, it gets written off because there just “isn’t time to deal with that right now.” But there is, unequivocally, always time to address misconduct and we must drastically shift attitudes within ourselves to match this fact. Especially as people in a position of authority within the room, stage managers cannot allow ourselves to be complicit in placing the needs of a show above the needs of the actual human beings creating it.

But when urgency is the driving force, it doesn’t actually make our work better, it only serves to squander thoughtful decision-making and cultivate environments where oppression and abuse thrive.

QUALITY OVER QUANTITY: Reschedule

White supremacist culture contaminates the stage management process even before we step into the rehearsal room. Just three families own the majority of Broadway theatres, and across the country, leadership like regional theatre boards skew heavily white, wealthy, and male. This leads to a labor structure that is directly driven by white supremacist ideologies that favor capital over the individual and quantity over quality. Theatres have a complex history of pushing against labor laws to continue working long hours—things like state requirements for days of rest or, recently, California’s Assembly Bill 5. For people with multiple jobs, people with disabilities that prevent long working hours, people with religious and cultural events outside of the Christian calendar, parents, students, and so many others, a capital-driven production schedule could be the final barrier barring them from a career as a theatre artist.

Many schedules, like the ones based on the NEAT rulebook in New England, land at or just shy of a full-time schedule. But unless the production pays a steady income comparable to a full-time job—and most don’t—it’s quite likely these long hours are just a portion of an artist’s workday. Rather than cramming in productions to maxed-out template calendars, we should standardize human-focused practices like tailoring schedules to the individuals working on a show and their specific needs.

There’s an array of capital-driven standards that we can start dismantling. Non-theatrical companies across the globe are already exploring the benefits of a four-day workweek, while the United States theatre industry still hasn’t yet caught up with decades-old labor reform, making us one of the few industries that still works six days a week. Just a single day off is simply not enough to rest and recover from the week. Providing a second day is crucial for people to see their families, work outside jobs, and even have a life as a human being. But cutting a day out does not necessitate tacking those hours onto another day. We are not obligated to try and puzzle every contractually allowed hour into our schedules.

One of the more egregious scheduling norms that has started to gain widespread scrutiny lately is the ten-out-of-twelve, a tech rehearsal where actors are generally called for twelve hours and get a two-hour break in the middle, and the production team typically works closer to fourteen hours or more. The rigor is compounded as these rehearsals take place during the longest week of the whole process—up to fifty-five hours on LORT contracts. It’s an exercise in diminishing returns and unnecessary burnout. At least from anecdotal experience, the last few hours of the ten-out-of-twelve often lead to the most frustration, most slip-ups, and work that will need to be redone the following morning. By focusing on getting the most hours rather than the best work and fair treatment of workers, we’re putting people in a position to fail—on top of putting their health and safety at risk.

Our industry has instilled the expectation of artists to put the show ahead of everything else, and it’s taking a massive toll on our safety and well-being. According to the Center for a New American Dream, people who work eleven or more hours a day are two and a half times more likely to develop depression and sixty times more likely to develop heart disease. In addition, multiple studies have shown long work hours and work-related stress to have adverse effects on a wide range of health impacts, including anxiety, sleep quality, substance use, mental health, physical health, and injuries. Prioritizing quantity over quality is a colossal tentpole of white supremacy that works to put organizational revenue before the physical and mental impact on the workers.

Change is possible. Places like Baltimore Center Stage have already committed to eliminating ten-out-of-twelves and standardizing a five-day rehearsal week. Stage managers must use whatever authority we have in the scheduling process to implement human-focused scheduling. We can explicitly work against urgency-driven expectations by proactively having open conversations about thoughtful, realistic, and sustainable scheduling that creates room for a team of diverse experiences. We should make a point of using breaks to de-stress, and taking days off, and encouraging those around us (particularly assistants, interns, and those without union protections) to do the same. By finding new ways to structure our production processes and taking care of the individual, we gain a multifaceted, well-rested, better-functioning, and healthier team.

By focusing on getting the most hours rather than the best work and fair treatment of workers, we’re putting people in a position to fail—on top of putting their health and safety at risk.

PERFECTIONISM & OBJECTIVITY: Expect and Accept Mistakes

One step to start tackling capitalist-driven tendencies in theatre spaces is by reframing our view of mistakes in the workplace. For stage managers specifically, there is a pervading expectation that we aren’t supposed to have any opinions or emotions—we are meant to be perfect robotic beings only around to serve the production. While it may be nice to feel omniscient and omnipotent from time to time, leaning into this idea can only set us up for failure since we are, in fact, neither of those things.

The expectation of perfection is explicitly taught in college programs like the one of our authors, John, attended—they were told a rehearsal should never have to pause on the stage manager’s behalf. Even things like small typos or grammatical errors get called out as an unacceptable flaw. Phyllis, another of our authors, vividly recalled a time when colleagues called her out in the middle of a production meeting for a misspelling in a past report. And while precision can be helpful, if the meaning is still perfectly conveyed, this is often unnecessary nitpicking that redirects energy away from the overarching goal of communication and, notably, undermines the talented stage managers out there with Dyslexia.

The issues of urgency and perfectionism blend together into a culture many stage managers have created, where we commend overworking as a badge of honor and chastise not using every possible second to work as a failure. It’s expected of stage managers to give up our free time by working through breaks or staying on call during our designated days off so we can respond to issues at a moment’s notice. When we factor in setup, cleanup, creating reports, sending daily calls, updating paperwork, responding to emails, and any other tasks added to our plates, stage managers often work overtime without compensation.

Black stage managers are often isolated within their theatre community and must constantly work to prove themselves among a sea of white and white-assumed peers. The burden to be perfect is amplified for BIPOC, women, queer people, disabled people, and especially individuals living at the intersection of those identities. There is no room for mistakes—they have to be practically infallible to be given a shot.

Artists at these intersections must assimilate to professionalism standards of how to talk, dress, and carry themselves, turning on their “stage management voice” and toning down their Black, feminine, and queer mannerisms to be listened to and respected by their colleagues. These artists are told over and over again—implicitly and explicitly—that if they don’t carry themselves in a way that makes white people comfortable, they won’t get hired again.

Slipping up, showing emotions “incorrectly,” or having opinions that conflict with the director could bar these artists from working at that theatre again. Not only is their own hiring potential at risk, but they have the additional weight of representing all BIPOC. “Stereotype threat”—the fear of acting in a way that confirms racial stereotypes—leads to a continual self-policing so that employers can’t point to them as a reason to not hire BIPOC artists in the future.

For white stage managers, the standard of perfectionism furthers the idea that stage managers should be objective in their work. Objectivity is, however, impossible for human beings to achieve—we bring in our viewpoints and experiences wherever we go. White supremacist culture will always deem white beliefs as the norm and best option. If white stage managers act from a belief that they’re just stating facts and following rules, they are ignoring the places prejudice is influencing their work and miss the opportunity to bring in new viewpoints.

Stage managers must question where their standards of professionalism are rooted and who they serve, and we must make space for forms of management and expression that are outside of our own. We can create a culture that gives everyone agency to speak up by embracing our mistakes and those of our colleagues as part of the generative process, and actively asking for the opinions of everyone in the room. Phyllis’s biggest advice for young Black stage managers is: “Stop apologizing and know that you’re enough. Practice taking up space without code-switching for other people’s comfort. Be okay with voicing your opinions, even if they disrupt the current flow and need time to be processed.”

These artists are told over and over again—implicitly and explicitly—that if they don’t carry themselves in a way that makes white people comfortable, they won’t get hired again.

POWER-HOARDING: Redefine the PSM-ASM Relationship

When brainstorming manifestations of white supremacy culture in stage management, the production stage manager (PSM) to assistant stage manager (ASM) relationship elicited some of the most potent responses from the authors of this piece. Many ASMs spoke about feeling disrespected, uncredited for their work, and given menial tasks outside their actual job duties in a way that gets brushed off as part of “earning our stripes.” The concept of being seen and not heard is alive and well for ASMs in many rehearsal rooms.

On top of all the standards of professionalism outlined above, ASMs often have their input diminished further with a version of the “one voice rule”—a principle that information from the stage management team should always come from the PSM. Quinn, one of the article’s authors, works as a female, disabled ASM, has often felt pushed into the role of the “quiet wife”—only speak when spoken to, and sometimes not even then. While this may create the appearance of a united front and streamlined communication, it often does the opposite. By shutting down other voices or requiring differing perspectives be filtered through one figurehead, it dismisses the ASM’s autonomy and slows down the process.

On one project where another author, Miguel, worked as an ASM, the PSM required the team to turn in their paperwork a week before tech to be “reviewed.” Miguel then got back a printed version with corrections in red ink, including notes on font choices (and what they should be) and an expectation of seeing “corrected” versions for review. This PSM and Miguel were the same age and working on a professional contract. We must always be on the lookout for infantilizing our colleagues—particularly BIPOC stage managers—in the guise of unsolicited “teaching” or “mentoring.”

One antidote to this mindset is focusing on completion, not competition—a mantra passed down by stage manager Deb Acquavella. Each member of the stage management team is working to achieve the same goal of a safe and smooth production. Having multiple points of view and avenues to turn to for information doesn’t reduce this goal but rather expands it. If an ASM knows an answer right off the bat, why wait for the PSM to dredge up the information just because they’re the designated one voice? We need to stop viewing the ASM as working below the PSM and instead put value on each person’s unique duties and expertise. We then become a collaborative team where everyone is valued for their contribution, rather than bolstering egos.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Amen. There's a line between strong "work ethic" and martyring yourself by refusing to have good work/life balance. Inflicting that attitude on casts doesn't make you a hero. PSM-ASM abuse has long been a problem because of the weird competitive nature of stage management. If these issues in the article had been solved already, I wouldn't have quit stage management. The culture around SMing is just too toxic for me.

Although I am in full support of your intentions, I cannot help but feel that your ideas are misguided. To racialize and indict certain work ethics that have actually served people in this profession (not to mention communities and audiences) very well, is to do a disservice to the many SMs out there who have done and continue to do exemplary work devoid of critical race theory ideology. I do hope that one day we can all see through the madness and make theatre in spaces that are safe from the dynamics of such theory, and rise above what essentially amounts to being racist in a whole new way, at the expense of truth, art, and expression... which after all, is at the heart of the reason we create art in the first place.

Hi Chad! I won't speak for the other writers, but for me personally, it's important to note that I do not view this as a complete indictment of anyone who has displayed these characteristics or to even call out the inherent morality of these characteristics. I myself have exhibited every single one of these characteristics, and it has (as you've mentioned) served me very well in this profession. But that's the key—it's served me well. Just because something is working for me, and has worked for certain people for quite some time, doesn't mean it's the best option or that we can't improve! Urgency and packed schedules, for example, have churned out a lot of good theatre over the years. But that doesn't mitigate the fact that these work ethics have also left people out (parents, people with second jobs, etc.) and created unsafe environments.

To your comments on racializing work ethics and being racist in a whole new way—these issues are far from new! The article by Jones & Okun is almost 20 years old, and the concept of white supremacist structures is even older than that. These characteristics aren't perpetrated only by white people, but they do serve to generally (though not always) benefit white people over BIPOC (as I mentioned for myself above) and they center that these work ethics are the best (and sometimes only) way to Stage Manage.

By unpacking these ideologies we aren't impeding art but breaking down barriers to creating it. I fully believe that by finding where our practices help us and where they hurt us (and who they help and hurt specifically), we will go extremely far in finding truth, creating art, and expressing fully.

Thank you Chad for your perspective and I will respectfully disagree. Just because a work ethic has worked for people in the past does not make it moral or ethical. It just makes it convenient. We are advocating for a people centered policies that allows the practice to be more accessible to everyone, not just the privileged. We are using critical race theory to shine a light on the problematic policies and norms that have been cultivated over decades. Many non-BIPOC SMs, from around the world, have reached out to let me know that they have also experienced a lot, if not all, the issues we mentioned in the essay. At least for me, I am asking for accountability, for the truth be told, to make sure my lived experienced is known. Art comes in many forms, and truth telling has alway been part of it. I hope that one day, you can also help shift the paradigm to people centered policies.

Thank you to all seven amazing authors for advancing this vital conversation! I look forward to sharing the ideas and recommendations with my students. There is much work to be done and reading this article has given me a lot of hope.

I was so excited to see your article also shining a light on the changes we can make as Stage Managers! Thank you for all the work that you and Lisa are doing, I can't wait to see what the next generation of SM students are going to bring to the table from having these conversations as part of their education

Thank you to all of the amazing authors of this essay and for the acknowledgment of the essay that Narda E. Alcorn and I wrote about anti-racist stage management education. I found the ideas and specific recommendations that you articulated in the essay compelling and engaging. Let's keep this critical conversation going!

Thank you both for the inspiration, both your wonderful article and your book. I fully embrace continuing the conversation going as there is much more to be said.