Rachel Chavkin’s ability to make each character’s movement motivated and strategic in a small box set designed by Riccardo Hernandez was astounding. On stage, tables were moved around to broaden the space, computers and whiteboards allowed Caden to give the audience and actors a brief history lesson about the history of Thanksgiving (with projections designed by David Bengali), leaving a lot of space for improv during the characters’ hilarious devising process. The play does not lend itself to flashy lighting, but Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew’s lighting design is also worth noting. Yew nailed the migraine-inducing lights that we all remember from high school without inducing an actual migraine, and she added sharp fade-outs that played up the comedy of each scene's conclusion.

Throughout the performance, it was unsettling to be reminded that each racist intermezzo was a real lesson plan that FastHorse pulled from the internet. In one, two Indians play with a gun. One shoots the other, and then one of the Indians hangs himself. During the performance, I could feel the audience members asking themselves, “Should I laugh?” and the tension as they wondered which racist preschool song would pop up next. You might be thinking, “these lesson plans have to be from a long time ago.” Nope. One song was from 2016, not even ten years ago.

These musical interludes highlighted to me, a Native person, the absence of Indigenous actors in the play. If Alicia was actually Native American, how might she combat these stereotypes to the audience? How many audience members have never met a Native person? How many people would assume that the content the children sing about is what Native American Heritage Month and the first Thanksgiving was all about?

FastHorse brings up these questions onstage at the top of Scene Two, when Logan and Jaxton are trying to figure out what to do about Alicia’s whiteness. Jaxton asks whether they should ask a Native American person what to do, but the closest person they can think of who may be associated with a Native person is Jaxton’s white friend who built a sweat lodge on his deck. The message of The Thanksgiving Play can be whittled down to one sentence that Logan utters: “I don’t know any Native Americans.”

The future that FastHorse and I push for is one in which Native actors would already be familiar to directors.

Logan and Jaxton are rightfully concerned about redface, the offensive practice of a non-Native American person wearing makeup or clothing, typically in a performance, to imitate an Indigenous person. This is what Alicia would be doing if she embodied a Native American character for the Thanksgiving Play. Towards the end of the show, when Jaxton and Caden try to intensify the devising process, they propose that they perform a show where they kick around decapitated Indigenous heads (as the pilgrims did according to historical documents). Blood goes everywhere: on the walls, the ceiling, and all over the cast. As Alicia is throwing fake blood around, she gets some smeared on her face. She literally has red on her face. Alicia and the rest of the characters, while trying to dance around the idea of redface, stepped right into it. They can’t create a culturally sensitive Thanksgiving Play with a cast of white people. Trying to imitate the experience of a Native person onstage without a Native presence in the room is redface.

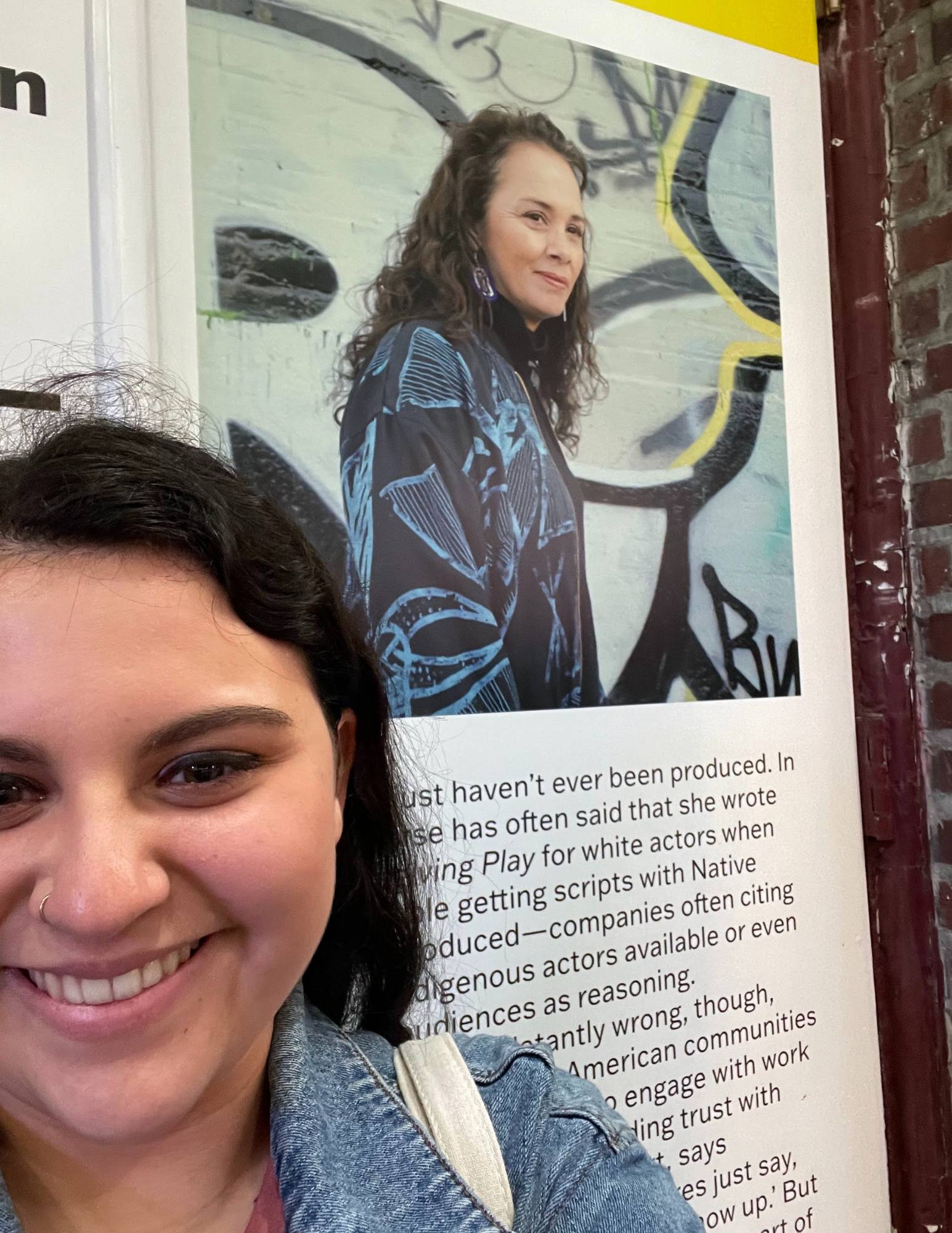

As the FastHorse profile in Playbill, which was reprinted on the front of the Hayes, says, “FastHorse lives her life among ‘well-meaning white people.’ You’ve met them. Heck, most of us probably are them.” She wrote The Thanksgiving People for white liberals so they could see themselves from her perspective, which is often the only Native perspective in the room.

I also know what it feels like to often be the only Native person in the room. Like FastHorse, who grew up in South Dakota, my Native dad was adopted and grew up in a primarily white, small town in Southern Minnesota. My dad, sister, and I were the only Native Americans in a too-many-miles radius. When I went to college in rural Iowa, this experience was only amplified as I began to step into my own identity as an Indigenous woman. I never saw my Native identity represented onstage. Many other Native Americans do not see themselves represented either, even if they live in bigger cities. FastHorse recognizes this reality too. In that profile on the side of the theatre, she states that “Broadway hasn’t been a familiar space for Native people.”

How long will it be until I see another Indigenous name on a Broadway theatre marquee?

While it may be disheartening to not see any Indigenous actors onstage at the Hayes Theater, FastHorse did this for a reason: producing The Thanksgiving Play gets a Native voice produced by requiring a cast of white (or white passing) actors. Now, theatre programs like mine in the Midwest are able to produce an Indigenous playwright because of the white cast. Many Indigenous playwrights have struggled to have their work produced because theatres believe that there is a lack of Indigenous actors available. FastHorse says that those ideas are blatantly wrong. Native actors do exist, but spaces like Broadway do not know or acknowledge them. I hope that The Thanksgiving Play challenges future directors to be unlike Logan and Jaxton, who wait for an unfamiliar face to arrive because they don't know any Native Americans, let alone Native American actors. The future that FastHorse and I push for is one in which Native actors would already be familiar to directors—a world in which Logan and Jaxton would already know the Indigenous actress coming to work with them.

Ignorance is not always intentional, as showcased by the songs that are featured in the racist intermezzi. The children who sing these songs only know what they have been taught. One of the best ways to combat this kind of ignorance is correct and intentional education. Sometimes people need an invitation into conversation that they would not seek out on their own. The Thanksgiving Play invites the audience to ask themselves how many Indigenous people they know. What lies and stereotypes have they believed about the Indigenous experience? Not because they are bad people, but because they were under- or misinformed.

The audience’s laughter at both the production of The Thanksgiving Play I directed and at the Hayes Theater leaves me with questions that haunt me as an Indigenous artist. What can I do better to support other Native artists? How long will it be until I see another Indigenous name on a Broadway theatre marquee? When can we see Native American artists both onstage and behind the scenes as playwrights, directors, and designers on Broadway? This show has given me—and many other Indigenous actors—hope that it won’t be long. Because Larissa FastHorse said “I want to be first,” other Indigenous artists like me can say, “I want to be next.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Love hearing about your journey from young director of this show to seeing it on Broadway. You have so much to offer and I can't wait to see what you do!!!